Our family gathers together each Sunday in Advent to sing carols. Most weeks I choose ‘O Holy Night’ and I particularly love the third verse:

Our family gathers together each Sunday in Advent to sing carols. Most weeks I choose ‘O Holy Night’ and I particularly love the third verse:

Truly He taught us to love one another,

His law is love and His gospel is peace.

Chains he shall break, for the slave is our brother.

And in his name all oppression shall cease. . . .

The Christmas carol reminds us that what we sing during this season is (should be anyway) true all year round. And a newly released book illustrates the point beautifully.

Hidden & Hard Work tells ‘stories of peacemaking in BC’s Lower Mainland,’ allowing eight local peacemakers several pages to tell something of their lives. The book is particularly welcome as we come to the end of this uniquely rancorous year in politics.

Editors Matt Balcarras and Katie Gorrie have chosen their subjects well. Balcarras is “a scientist and writer who lives in the traditional territory of the Musqueam and Tsawwassen with his wife and three children.” Gorrie is a poet, mother and editor in Montreal. Equally important to the project are Lee Kosa, who did a tremendous job designing the book (and happens to be Balcarras’s pastor at Cedar Park Church in Delta) and Rachel Pick, who took all the pictures, which are impressive.

Good news from peacemakers

Some of these peacemakers I know because I have written on them and their projects over the years.

Some of these peacemakers I know because I have written on them and their projects over the years.

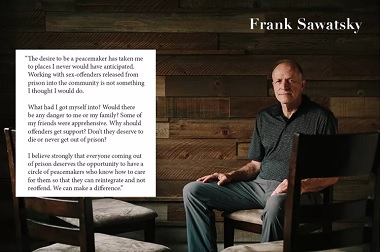

Frank Sawatsky, for example, was a coordinator for several years with Circles of Support and Accountability (CoSA), which works with sex offenders when they are released from prison.

In Hidden & Hard Work, Sawatsky says:

The desire to be a peacemaker has taken me to places I never would have anticipated. Working with sex offenders released from prison into the community is not something I thought I would do.

What had I got myself into? Would there be any danger to me or my family? Some of my friends were apprehensive. Why should offenders get support? Don’t they deserve to die or never get out of prison?

I believe strongly that everyone coming out of prison deserves the opportunity to have a circle of peacemakers who know how to care for them so that they can reintegrate and not reoffend. We can make a difference.

I’ve posted stories about Loren Balisky and his work with Kinbrace Refugee Housing and Support several times, and met Jodi Spargur many times as she works for justice and healing between the church and Indigenous peoples.

The others I don’t know, but am delighted to hear from them in these pages – the book format gives them enough space to tell us something of who they are as well as what they do.

Balisky reflected upon his impulse to welcome people from around the world:

Throughout my childhood, I experienced the repeated turmoil of leaving family [missionaries in Ethiopia] to attend boarding schools. I cried each time I left home, and sometimes cried with happiness at reuniting with my parents after weeks or months apart. To this day, when I meet someone dislocated from their home, I have an urge to respond, somehow, to the fear, anxiety or uncertainly they might be experiencing. . . .

As Peter Elliott, Dean of Christ Church Cathedral, says in the Foreword, “the stories told are as fresh as headlines in the news and as relevant as the issues faced daily in our neighbourhoods and communities.”

Peacemaking isn’t easy

Matt Balcarras

Balcarras introduces the book with a note of humility, relating his less than saintly response to a neighbour’s complaint about his dog:

It’s easy to list off examples of interpersonal and inter-community conflict that need addressing, and it seems difficult to imagine how we might live at peace amongst these serious issues when our anger flares up over minor ones. To put it simply, I write all this recognizing how hard it is to be peaceful, how easy it is to fight for what we want and not what is good. . . .

Here’s one thing I’ve started to learn from this process and from listening to new stories: peace is more complicated, more multi-dimensional, than I once thought.

Some of the most compelling portions of the following stories take up this theme.

Jodi Spargur, for example, describes peacemaking as a process that is somewhat foreign to her nature:

I’m not naturally a person of peace. Nor do I come from a people or tradition of peace.

Niki Frew and her family have fostered several kids, and often gets this kind of comment: “You’re a saint. Good for you. I don’t think I could do it.” Her response to such comments:

Honestly, I couldn’t either, if it wasn’t for the grace and command of God. . . .In case you’re able to dismiss this story because I’m somehow unlike you: I do not have superhuman patience, nor exceptional parenting skills. (I used to think that way of foster parents. Still do sometimes, actually.) My energy level is not high and I hate being woken up in the night. I struggle with selfishness and still battle my desire for comfort and ease. But somehow God can still use me.

Peace and justice

A recurring theme in Hidden & Hard Work is that you can’t have true peace without justice. Balcarras says this in the Introduction:

I believe – and probably you do, too – that life is better when we learn to live in peace, but this is where things get difficult. . . . Consider this: many times the absence of overt conflict (‘peace’) is produced by hidden injustice. One group of people gets peace and quiet but through the systemic oppression of others . . .

Jodi Spargur puts it this way: peace is made when we live so that “nothing is missing, nothing is broken.” Our peace is connected to the peace of our neighbour; peace is made when we make sure that everyone is included and no injustice is ignored. . . .

Things do indeed get difficult here, because fellow Christians – not to mention those outside the church – often disagree about what justice means in particular situations. And that leads to a couple of caveats about the book.

Peace where there is no peace

The chapter on Beth Carlson-Malena will be jarring for some. She is clearly a warm Christian doing some valuable work as director of community for Generous Space Ministries, which she describes as “a national Canadian organization that works to eliminate fear, division and hostility at the intersection of faith, gender and sexuality.”

She tells of growing up as a Baptist pastor’s kid, attending Regent College and being drawn to another young woman there. Over time they decided to come out publicly, and to marry.

Beth and Danice went on to work with Generous Space: “We are three years into this work and we have met some incredibly courageous human beings of whom we are fiercely proud.”

Thankful as Carlson-Malena is for generous spaces, she still feels there is a long way to go: “Finding interior peace is a difficult journey, but it’s even more difficult to find our place in the broader Christian world.”

Even though “most folks in our community were raised in evangelical denominations” (and feel comfortable with many of the theological convictions and spiritual heritage), she says, “evangelical congregations are often like those who say, ‘Peace, Peace’ where there is no peace’ (Jeremiah 6:14).

Describing three settings in which LGBTQ+ people are accepted, but only partially, she says:

‘Don’t ask, don’t tell is not the peace we seek. . . . Second-class citizenship is not the peace we seek. . . . Being merely tolerated, tokenized or patronized is not the peace we seek. . . .

This is hotly contested territory. Can there really be peace when each ‘side’ is certain of its ground?

In the meantime, I do see Carlson-Malena as a peacemaker and hope her aspiration will be borne out:

Because our very existence audaciously bridges the span between the supposedly mutually exclusive LGBTQ+ and Christian worlds, we are well equipped to build further bridges of reconciliation and peace.

Converting the heathen

In his Foreword, Peter Elliott says the church understands its mission differently in the 21st century:

It is not about ‘converting the Heathen,’ as a former generation imagined it, but about participation in the mission of God – the missio Dei.’ This includes all the work done to make peace and promote justice so that life on this planet can flourish.

As a converted former heathen, I would hate to lose our missionary/evangelism heritage (the pejorative term ‘heathen’ is long gone). My experience is that those who focus on proclamation and a traditional understanding of the Great Commission sometimes overlook themes of justice and community, while those who lean to a more social gospel are often not enthusiastic about more explicit outreach. But that is not always the case by any means; there are many examples of Christians who have offered a pretty fair balance.

Addie Tinholt

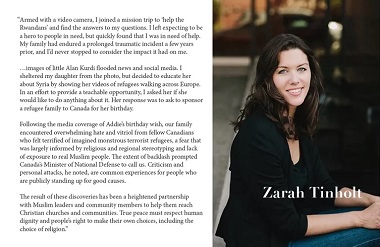

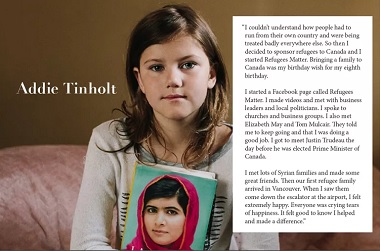

Two of the most moving stories are those of mother and daughter, Zarah and Addie Tinholt. Both are absolutely delightful examples of welcoming spirits – especially with regard to refugees and Muslims.

Zarah writes about how to balance talk and action:

True peace must respect human dignity and people’s right to make their own choices, including the choice of religion. Despite the call to preach and make disciples, the Christian call is not a call to push the conversion of every single person and rule the world under one religious banner

Then she describes Addie’s experience as she experienced other cultures and beliefs:

In the wake of my daughter’s involvement with refugees and our immersion into the Muslim community, she asked to be baptized. I bristled at her request because I wanted to make sure a choice like that would be made for the right reasons. . . .

Instead of slowing her down, the diversity of experiences and friendships only emboldened her. She learned that there is compassion and beauty in every individual, and that she can honestly support and celebrate the freedom, identities and choices of others – even if they don’t align to her own ideals – while remaining firm in what she values and believes.

Bold interaction with others is a sign of faith; protectiveness and insularity demonstrates fear.

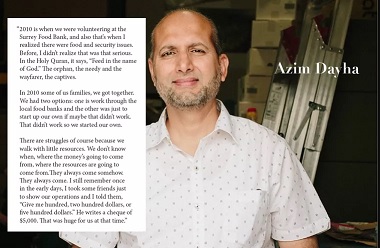

The final chapter features Azim Dahya, who arrived in Vancouver from Kenya in 1993 and began working with a board in 2010 to form the Muslim Food Bank in Surrey. He illustrates Elliott’s point that:

The final chapter features Azim Dahya, who arrived in Vancouver from Kenya in 1993 and began working with a board in 2010 to form the Muslim Food Bank in Surrey. He illustrates Elliott’s point that:

The missio Dei – God’s work – is not the sole possession of Christians; people from all the world’s religions share in the hidden but hard work of peace and justice.

Well regarded project

In case my encouragement to read this book is not enough, here are snippets from three endorsements by local leaders – any one of whom could have appeared in the book:

- Tim Kuepfer: pastor, Vancouver Chinese Mennonite Church: “These Vancouver-rooted peacemakers are patiently and tenaciously chipping away at systemic injustices within our own communities. Often they feel compelled to challenge, disturb and even disrupt our complacent and unjust expressions of ‘peace.'”

- Tim Dickau pastor, Grandview Calvary Baptist Church: “After reading these stories, I found myself wanting to join them in resisting our deeply polarizing political climate and devote myself anew to the road much less-traveled today, Jesus’ way of making peace.”

- Dena Nicolai, chaplain and refugee support mobilizer, Christian Reformed Churches of BC: “Each voice affirms, in its own way, what one of the story-tellers notes: ‘any impulse towards peace is work of the Spirit, an almost visceral experience of cool water poured over a blistering burn.'”

Hidden & Hard Work could be the first of a series; I hope it is.