Both the City of Vancouver and faith communities must modify their ways of relating to each other if we are to achieve ‘A Healthy City for All.’

In the 15 years I’ve been helping churches and municipalities engage with one another, I’ve never been more hopeful that genuine dialogue is keenly desired on both sides of the table – nor more convinced that time is running out for it to happen with good outcomes.

Both sides are, I think, starting to recognize that they have been relating to each other transactionally and that neither side can experience what it needs in this mode.

However, no one appears to know how to move beyond transactional exchange, into properly boundaried collaboration that advances not merely the priorities of city halls or of local congregations but the common good – the shalom – of all .

Municipalities are experiencing extraordinary pressure to guarantee the well-being of the people and places in their jurisdiction, but it is largely beyond their power to do so.

In our era of global capitalism, the geo-political landscape is becoming “spiky,” to borrow a phrase from the urban geographer Richard Florida. Wealth, opportunity and therefore people are migrating to a select few metropolitan regions, rendering national economies and political systems increasingly subservient to localized yet globally intertwined dynamics effectively governed more and more by private market values and priorities.

Florida and others go so far as to suggest we may in essence be returning to a system of city-states, which over the long span of human history has predominated.

It’s no mystery where Vancouver stands in this spiky global landscape, but the City certainly does not have the powers of a city-state. Senior governments control virtually all the main legal and regulatory levers that could limit or direct the flow of money and people into Greater Vancouver from outside the province.

Senior governments are also the primary regulators and funders of bedrock quality-of-life issues such as housing affordability, utilities, transportation, health care, education, the environment. Moreover, senior governments are defunding or underfunding the social safety net, defaulting responsibility for the consequences onto local governments.

The City can set its own targets, devise its own strategies, allocate its own dollars; but it cannot achieve any of these at sufficient scale unless senior governments align theirs.

The municipal toolbox for urban flourishing is very much smaller in Canada than it is the United States or other parts of the Commonwealth. Basically, as far as I understand, the City can do little more through its bylaw and zoning powers than to say in broad strokes what is allowed to be done on a parcel of land. Everything else is more or less aspirational – the City can say what is allowed and what is not, but it cannot force an outcome unless it can pay for that outcome by itself.

For instance, it can make a Rezoning or Development Permit conditional on the landowner paying for some public amenity (affordable housing, daycare space, public art, etc.) but it cannot force the landowner to go ahead with their proposed project; the owner can drop it. For another, an owner can choose to close a rental building rather than fix it up when hit with a Standards of Occupancy infraction.

So the City’s ability to achieve most of its goals is limited to its ability to pay for those goals through taxing properties and – more often – persuading or incentivizing others (especially senior governments and landowners) to bear most of the costs.

There are two other aspects to why the City’s plans are largely and irreducibly aspirational, beyond its power to secure on its own. First, a lot of what makes for urban flourishing, for the well-being of people and places, is communal rather than governmental in nature.

Second, well-being is less a condition that results from an accumulation of desired elements operating in an orderly and controllable fashion than it is a quality that emerges in the synergistic relationships of people who are learning to live in harmony with the land and waters of their region and with each other (and with the Creator, people of faith would add).

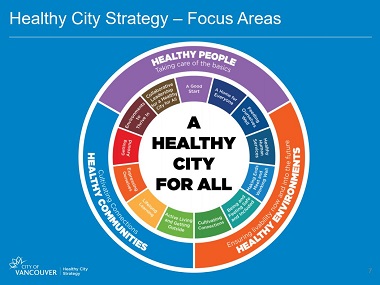

As I mentioned in the first two instalments of this series of articles, the City of Vancouver’s vision for urban flourishing is laid out in its Healthy City Strategy. City staff and politicians are keenly aware the Strategy has no hope of succeeding unless they can attract enthusiastic participation not just from senior governments and the marketplace but more crucially, in the long run, from residents and community groups. The Strategy hinges on participatory democracy and plain old neighbourliness.

This is where I think the City is recognizing it needs to learn new habits, that it has been far too transactional if not downright poorly engaged. The City is also recognizing that ideal partners would be community-based groups who own property and have similarly holistic understandings of urban flourishing.

Congregations, then, are better placed (literally!) than any other class of potential partners.

Group conversation at Community-Serving Spaces Stakeholder Forum (photo is from Summary Engagement Report).

So I was very pleased indeed to facilitate two half-day Stakeholder Forums for the City back in May, so that staff from five departments could get input on major new policies they are drafting to help preserve, enhance and expand “community serving spaces” held in nonprofit hands.

I was even more encouraged to hear Mary Clare Zac, the City’s Managing Director of Social Policy and Projects, open the second Forum, focus on places of worship, by telling more than 40 faith leaders that if the City has community advisory committees on matters such as dog parks then it is high time for the City to establish some kind of ongoing dialogue with communities of faith.

But the forum made something else painfully clear: quite apart from whatever the City needs to learn for moving past transactional relationships to genuine partnership with community groups (and other sectors), the City has absolutely no idea how to relate to religious groups as communities of faith.

Not only is the City incapable of recognizing “common good” or public value in places of worship as places of worship, it currently gives no room at all in its current vision of urban flourishing for spirituality of any kind. The topic appears nowhere in the Healthy City Strategy or other guiding documents.

The Community-Serving Spaces Study was carried out for the City of Vancouver.

The City isn’t entirely to blame; it is just following cultural trends. Within liberal democracy (which was conceived in horrified reaction to vast slaughter and destruction during religious wars that wracked Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries), religion has been explicitly relegated to the private realm.

This, added to a host of other secularizing trends in the formerly Christian West (accelerated by the particular history of BC), means the City has no language or conceptual framework for partnering with faith communities.

At best, the City can only treat us like other charities. And so the City is truly puzzled when we object that that entire neighbourhoods are being built now without any room set aside, let alone any incentive being offered, for sacred space. Or that when we come forward to redevelop our properties, depending as we must on density bonuses to generate financial value to make our proposals viable, the City is effectively forcing us to sacrifice congregational space for other uses it chooses. Or that, while we are keen to make our spaces available for affordable housing and social services and cultural programming, we do so precisely because of our faith, not only because of our humanity or urbanity.

Jonathan Bird

So I believe it is on us, as people of faith, as ambassadors of Christ, to find a way to build a bridge of language back to the public square, to fashion a shared vocabulary with City planners and politicians. To demonstrate how our worship spaces are in fact public amenities because our worship proceeds directly into community service – that our liturgies, our “work of the people,” extend into our neighbourhoods as habits that help create the commons.

Jonathan Bird is church relations specialist with Union Gospel Mission.

Link to part 1 and part 2 of the series.

It would appear that getting Christians to run for office at the civic and provincial levels would provide an opportunity for our faith communities to have a voices heard and build bridges with the city and province. We have a government currently in BC that, by its behaviour, indicates no interest in participatory democracy as evidenced by its preference for one-way communication from itself to the rest of the province. It is moreover, a party of secularists, unlikely to understand people of faith. MLAs with a voice and a burden to work with and for faith communities are sorely needed.

I read the second half of this article with a lot of interest. How do you propose “people of faith, as ambassadors of Christ . . . find a way to build a bridge of language back to the public square?” Are there movements we can join?

Hi Angela, as far as I know there isn’t any movement here in Canada for bridging congregational and municipal activities for the common good. Cardus Social Cities is a project of a Christian Reformed think tank based in Ottawa that is generating solid tools and ideas, but they’re not able to do much mobilizing. Edmonton’s Abundant City initiative involves a lot of people of faith but seems essentialy secular. I and others are hatching plans here in the Lower Mainland. You can contact me at [email protected]