Alan Hirsch is founder of 100Movements, Forge Mission Training Network and Future Travelers, and the author of several influential books.

Missional leader Alan Hirsch will be a keynote speaker at Mission Central: SERVE (formerly Missions Fest) later this week, January 29 – 31.

Following is an excerpt from his book The Forgotten Ways (Brazos Press 2006, 2016).

I wish to briefly restate here what seems an obvious fact, but one that is often overlooked. For authentic missional Christianity, it is the God revealed in the specific man Jesus who plays the absolutely defining role.1

Whatever we might now know of God is qualified by how he is revealed to us in the historical and risen Jesus. In other words, there is no way around Jesus to get to God.

Our identity as a movement, as well as our destiny as a people, is inextricably linked to Jesus, the Second Person of the Trinity. In fact, our connection to God is only through the Mediator – Jesus is ‘the Way’; no one comes to the Father except through him (John 14:6).

This is what makes us distinctly Christ-ian. This is what I call Messiah//Messianic: the idea that Jesus the Messiah, everything about him, his person and his work – without reduction – sets the primary template for the movement that claims his name.

We should always expect a correspondence between the Founder and his followers, individually and collectively. If the movement fails to resemble, act and sound like the Founder, then something must be deeply wrong.2

At its very heart, Christianity is therefore a messianic movement, one that seeks to authentically and consistently embody the life, spirituality, teachings and mission of its Founder. We have made it so many other things, but this is its utter simplicity.

Discipleship is becoming like Jesus our Lord and Founder and experiencing his life as it is lived through me/us, and it lies at the epicenter of the church’s task. It means that Christology must define all that we do and say.

It also means that in order to recover the ethos of authentic Christianity, we need to refocus our attention back to the Root of it all, to recalibrate ourselves and our organizations around the person and work of Jesus the Lord.

It will mean taking the Gospels seriously as the primary texts that define us. It will mean acting like Jesus in relation to people outside the faith; as God’s Squad, a significant missional movement to outlaw bikers around the world puts it, “Jesus Christ – friend of the outcasts.”

Christianity beyond the sacred and the secular

A genuinely messianic monotheism, therefore, breaks down any notions of a false separation between the ‘sacred’ and the ‘secular.’ Abraham Kuyper understands this when he says, “There is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry, Mine!”3

If the world and everything in it belong to God and come under his direct claim over them in and through Jesus, then there can be no sphere of life that is not radically open to the rule of God. There can be no non-God area in our lives and in our culture.

If this is so, then if churches, whether they be high or low church, experimental or sacramental, seek to set up special ‘sacred spaces,’ they fall into the tempting error of communicating that there is in fact a sacred-secular divide.

By setting up a place that we call ‘sacred,’ what are we thereby saying about the rest of life? Is it not sacred? We cannot escape the conclusion that by setting up so-called sacred spaces we, by implication, make everything else ‘not sacred,’ thereby assigning a large aspect of life to a non-God, or secular, area.

Following the impulses of biblical monotheism, rather than setting up some sacred spaces, we must make all aspects and dimensions of life sacred – family, work, play, conflict and so on – and not limit the presence of God to spooky religious zones.

I use this example simply to highlight how deeply dualism, including as it does the idea of the sacred-secular divide, penetrates our understanding, and how biblical monotheism helps us to develop an all-of-life perspective.

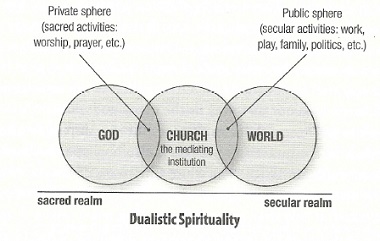

Dualism distorts our experience of God, his people and his world.

Dualism distorts our experience of God, his people and his world.

People involved in dualistic spiritual paradigms experience God as a church-based deity and religion as a largely private affair.

Church is conceived as a sacred space: the ethereal architecture, lighting, music, rituals, religious language and culture all collaborate to make this a sacred event not experienced elsewhere in life in quite the same way.

In other words, we go to church to experience God, and in truth God is there (he is everywhere and particularly loves to abide with his people), but the way this is done tends to create an erroneous perception that is very difficult to correct – that God is really encountered only in such places and that it requires an elaborate priestly/ministry paraphernalia to mediate this experience (John 4:20-24).

This dualistic spirituality has been called a number of things, but perhaps the idea of the Sunday-Monday disconnect brings the matter to the fore. We experience a certain type of God on Sunday, but Monday is another matter – “This is ‘the real world,’ and things work differently here.”

How many times have we professional ministers heard variations of that phrase? “You don’t really understand. It’s just not as easy for me as it is for you. You work in the church with Christians,” and so on.

The two “spheres of life,” the sacred and the secular, are conceived as being infinitely different and heading in opposite directions. It is left to the believer to live one way in the sacred sphere and to have to live otherwise in the secular.

It is the actual way we do church that communicates this nonverbal message of dualism. The medium is the message, after all. And it sets people up to see things in an essentially distorted way, here God is limited to the religious sphere. This creates a vacuum that is then filled by idols and false, or incomplete, worship.

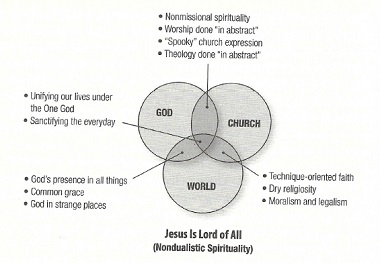

Now, using the same elements and realigning them to fit a non-dualistic understanding of God, church, and world, we can reconfigure this schema as follows:

Seeing things this way leads us to embrace an all-of-life perspective on our faith.

Seeing things this way leads us to embrace an all-of-life perspective on our faith.

By refusing the false dualism of sacred or secular, and by committing all of our lives under Jesus, we live out true holiness. There is nothing in our lives that should not and cannot be brought under this rule of God.

Our task is to integrate the disparate elements that make up our lives and communities and bring them under the one God manifested to us in Jesus Christ.

If we fail to do this, then while we might be confessing monotheists, we end up as practicing polytheists. Dualistic expressions of faith always result in practical polytheism. There will be different gods that rule the different spheres of our lives, and the God of the church in this view is largely impotent outside the privatized religious sphere.

Christocentric monotheism demands loyalty precisely where the other gods claim it, and this is as true for us as it was for our spiritual forebears. Make no mistake, we are surrounded by the claims of false gods in our own way as the many gods clamor for our loyalties and lives as well – not the least of these the worship of wealth and the associated gods of consumerism.

But this is also how apartheid was birthed and developed in South Africa. The white Christians of South Africa would not integrate their national situation under the lordship of Jesus, so a false god was invoked to rule over white politics. The result was a deeply sinful and ungodly crushing of the people of color in that land. When God’s people fail to bring a significant domain of society under the direct way of Jesus, then it becomes autonomous and susceptible to the rule of false gods, and many sins result.

In this way, many Christians who are confessing monotheists end up being practicing polytheists. Isn’t it interesting that most churchgoers report a radical disconnect between the God who rules Sunday and the gods that rule Monday?

How many of us live as if there were different gods for every sphere of life? A god for work, another for family, a different one when we are at the movies, or one for our politics. No wonder the average churchgoer can’t seem to make sense of it all.

This results from a failure to respond truly to the one God. This failure can be addressed only by a discipleship that responds by offering all the disparate elements of our lives, including the various domains of society, back to God, thus unifying our lives under his lordship.

Footnotes

- See Frost and Hirsch, Shaping of Things to Come, 105–14.

- I urge readers to explore the significance of Jesus for the character as well as the mission of his people in my book with Mike Frost, ReJesus.

- Kuyper, “Sphere Sovereignty,” 488.

An absolutely essential message. Three cheers, Alan Hirsch. The most crippling heresy for Christians, and for the world, is dualism.