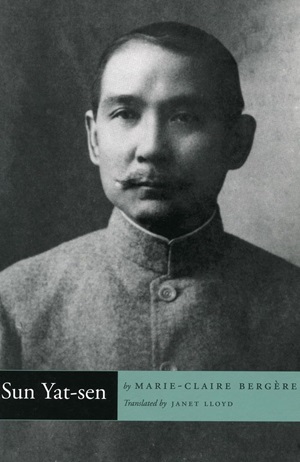

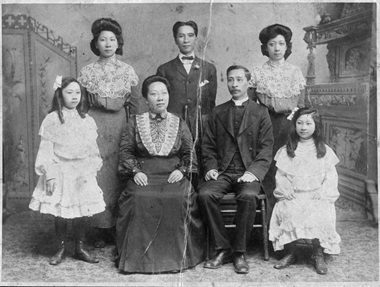

Dr. Sun Yat-sen visited BC twice. Here pictured at Yucho Chow’s photographic studio in Vancouver. Now in Burnaby Village Museum, HV975.5.60.

With all the attention being paid to Chinese interference in Canada’s political process, this is a good time to remember that just over 100 years ago the influence flowed both ways.

A new book focuses on Chinese political history in Vancouver, Victoria and other North American cities, especially along the Pacific coast.

In Transpacific Reform and Revolution: The Chinese in North America, 1898 – 1918 (Stanford University Press, 2023), Zhongping Chen pays close attention to Chinese leaders such as Kang Youwei and Sun Yat-sen, who spent much of their time mobilizing Chinese people in North America and worldwide.

The stakes were high, as a somewhat bewildering variety of movements sought to reform the Qing (Manchu) Dynasty, or to overthrow it completely, while also grappling with Western imperialism.

Kang’s reformist approach thrived for a time, before dissipating, while Sun prevailed – through major ups and downs – and remains a father figure for the nation, still recognized worldwide.

Reformers & revolutionaries

Elisabeth Forster introduces her valuable Made in China Journal interview with Zhongping Chen – a professor of Chinese history and the history of the global Chinese diaspora at the University of Victoria – with this comment:

Elisabeth Forster introduces her valuable Made in China Journal interview with Zhongping Chen – a professor of Chinese history and the history of the global Chinese diaspora at the University of Victoria – with this comment:

His time frame is the period between the failure of the Hundred Days’ Reform in 1898 and 1918, a time when, as he writes, Sun Yat-sen ‘and his followers turned to the militant fight for a single-party state’ (p. 14). This is a fascinating study that shows Chinese reformers and revolutionaries of the period in an entirely new, much more pragmatic light.

Chen discusses the status Kang and Sun had in their networks and the way these networks operated – from business activities and funding through membership fees, to the lawsuits they levelled against each other, and even assassinations.

Chen also shows how they clashed with other Chinese communities, such as Chinese Christians or others living in Chinatowns, over ideology and business, and how they negotiated a tricky relationship with the West (both its politics and its different social groups). Transpacific Reform and Revolution forces us to rethink not merely reform and revolution, but also reformers and revolutionaries, as well as the political parties that emerged from their activities in the early republic.

I will focus mainly on the two main characters’ dealings in Vancouver and Victoria.

Kang Youwei

Kang Youwei spent considerable time locally during four visits; he developed CERA in Vancouver and Victoria.

Kang Youwei was a scholar, but he also proved adept at political organizing. He began his reformist activities in China, when he refused to bind his daughters’ feet. He retained the Confucian ideal of service to society and was impressed by Buddhists’ spirit of compassion – but he also admired many elements of Western culture.

After escaping arrest for his active support of the 1898 Reform, he fled China for Japan and then Victoria, where fellow migrants from Guangdong Province gave him a warm welcome. However,

When Kang Youwei’s ship reached Victoria on the evening of April 7, 1899, he immediately faced the same discriminatory treatment as other Chinese immigrants, including being subject to the $50 (CAD) head tax imposed on every Chinese immigrant, with the exception of certain non-labor passengers.

Kang was very much concerned with the situation in China, but also with conditions in North America – a point Chen said has been widely overlooked. Chen wrote:

Kang’s preface to CERA’s regulations condemned not only the foreign invasion of China, but also anti-Chinese racism abroad, including the Chinese Exclusion Acts imposed by the American government from 1882, the Chinese Head Tax in Canada and even the harassment of the Chinese by white teenagers on North American streets.

Kang stressed that the major purpose of his reformist movement was to save not only the Guangxu Emperor and the Chinese nation, but also the “yellow race” (huangzhong), especially overseas Chinese, from racist discrimination.

Part of his support derived from his concern about local business and political interests:

In order to unite all Chinese, he planned the reformist association at the local, national and global levels. Kang also called for the development of newspapers, banks and the like, and solicited for donations to these business ventures.

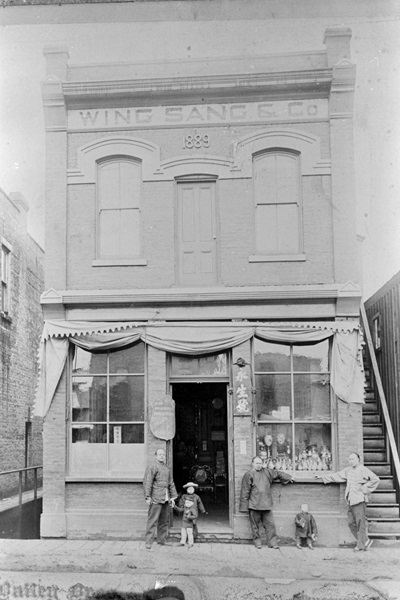

Yip Sang with children and family members in front of 51 East Pender ca.1890s. CVA 2008-010.4050

Kang formed CERA (Chinese Empire Reform Association) in 1899 in order to reform China under the Guangxu Emperor. It “would become the first truly global political organization of the overseas Chinese.”

Chen said that after Kang was unable to enter the United States to solicit support for political reform in China . . .

. . . A few merchant leaders of Vancouver’s Chinatown had successfully turned his proposal from a transnational corporation into practical efforts to organize overseas Chinese. . . . According to a Vancouver newspaper report, the founders of the transnational corporation included Yip Sang, his nephew Yip Yen and five other Chinese merchants in the local Chinatown.

An interesting side note is that “Yip Sang, the richest merchant and senior patriarch of the Yip lineage in Vancouver’s Chinatown,” built the Wing Sang Building, which as of last summer houses the Chinese Canadian Museum.

Chen said there has been some uncertainty about where exactly CERA began; he concluded:

Thus, CERA, which evolved from the transnational corporation created by Yip Yen and other merchant leaders of Vancouver’s Chinatown two months earlier, was formally established in Victoria in late July 1899.

Kang was personally quite well received in North America. For example, he met with the mayors of Vancouver and New Westminster during his initial visits, and his lecture at Vancouver city hall was attended by about 1,000 Chinese, with Japanese and Caucasian guests. He would later meet with Canadian Prime Minister Laurier and President Roosevelt, twice.

After about 1905 – 1910, the popularity of Kang and the reformers began to decline, as more revolution-minded leaders came to the fore.

Sun Yat-sen

Statue of Sun Yat-sen at Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall in Guangzhou, China.

Sun Yat-sen (briefly) led the Republic of China, but he is now considered ‘a forerunner of the revolution’ in China and ‘father of the nation’ in Taiwan.

However, such a favourable legacy was by no means assured during his lifetime. He fostered numerous failed rebellions. He was forced out of China more than once, deported from Japan, kidnapped in London, and widely disparaged as an opportunist, lacking in strategic insight and unduly friendly with imperial powers.

However, he was personable, magnetic, persistent, focused on achieving power – and fortunate.

Sun spent less time in this area than Kang. His first trip, in 1897, lasted just a couple of weeks, most of it in Victoria. He had been abducted by the Qing delegation in London, England in October, 1896, before being released under diplomatic pressure from the British government.

Thus, as he travelled on to Canada, “he was being shadowed by both a Qing diplomatic official and a British private detective hired by the Qing legation in London. At the Montreal customs house, Sun disguised himself as a Japanese man and registered under the name of ‘Dr. Y.S. Lun.'”

Chen described the recollection of that time by one of Sun’s “close comrades,” Feng Ziyou:

[He] claimed that Sun did not have enough time for revolutionary mobilization among the Chinese in Vancouver and Victoria. Feng deplored that this lost opportunity allowed Kang Youwei to launch CERA in Canada the next year and dominate Canadian Chinatowns through a reformist movement over the next decade . . .”

Things had changed by the time of Sun’s trip to Vancouver in February, 1911. Feng had started a supportive newspaper in Vancouver. More importantly, even reformers were despairing of supposed Qing reforms. Later that year the 1911 Revolution would topple the Qing Dynasty, which had ruled China since 1636.

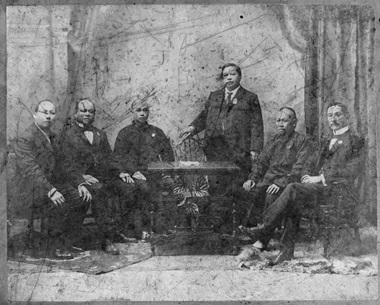

The first executive officers of CERA, 1903. From left: Ho Jun Chung, Yip Sang, Kee Lee, Yip Yen (standing), Huang Yushan and Won Alexander Cumyow (now being considered for the new Canadian $5 bill). City of Vancouver Archives, Paul Yee, AM1523-S6-F58-

Sun visited about 10 cities and towns in BC. Though he faced “a potential threat to his life from a member of the local CERA chapter . . . evidently, most reformist leaders of the local CERA chapters had turned from hostility to tolerance of and even support for Sun’s fundraising activities for an anti-Qing revolution . . .”

Chen described how the Revolutionary Alliance in Canada and the United States built on CERA’s legacy:

In the aftermath of Sun’s fundraising tour across Canada, Feng Ziyou took the opportunity to establish the Revolutionary Alliance’s first Canadian chapter in Vancouver in 1911. .. .

Under Feng’s leadership, this chapter actively mobilized its members to vote in the annual election of the Chinese Benevolent Association in Vancouver. They used their kinship and local fellowship to influence other Chinese voters in the election and successfully defeated almost all reformist candidates from the local CERA. . . . the success of the local Revolutionary Alliance in this election again shows how it inherited the institutional legacy of Kang Youwei’s political reforms.

CERA Canada’s headquarters moved from Vancouver to Victoria in 1910 (where it had begun), weakened, but not decimated.

Sun was still travelling the world, raising money and support, when the 1911 Revolution began October 10. He returned promptly to China and was named provisional president of the Republic of China January 1, 1912.

Kang and Sun

Kang and Sun both came from Guangdong (Canton) province in southern China, and shared some ideals, but they were definitely rivals. Sun and his Revive China Society sought to collaborate with Kang and other reformist exiles in Japan in 1898, but was rebuffed.

Marie-Claire Bergère, in her biography of Sun Yat-sen, said:

Marie-Claire Bergère, in her biography of Sun Yat-sen, said:

Everything made for distance between Sun and Kang, who considered each other as, respectively, “uneducated” and “a corrupt Confucian.” Kang regarded Sun as a rebel without dignity, won over by Western materialistic ideas. Sun regarded the legitimation of reform by means of a reinterpretation of Confucius and the Classics, to which Kang had devoted so much effort, as a scholastic and pointless exercise.

The divergent opinions were exacerbated by mutual jealousy, each seeking to promote his own authority, and by the apparently insurmountable differences between their social origins and intellectual backgrounds.

By 1900 the two parties were rivals in seeking support from the overseas Chinese community.

By 1904, Chen wrote, Son’s “direct clashes with CERA leaders even led to attempts to assassinate him.” Kang wanted supporters “to get rid of Sun before Kang’s own American tour.”

Violence was a serious problem in China during this time, with the Boxer Rebellion, regular uprisings, etc. But it also spilled over to North America. Kang himself appears to have hidden out on Wen (Coal?) Island north of Victoria in order to avoid being killed. And Chinese Republican politician Tang Hualong was assassinated by Wong Chong, a member of the Chinese Nationalist League in Victoria.

Chen suggests there may have been some softening in the relationship between Kang and Sun, describing an encounter in Shanghai:

In 1913, a young merchant from Victoria, Lin Libin . . . asked whether Kang Youwei’s CERA had indeed tried to protect the Manchu monarchy. Sun’s reply indicated that both CERA and the revolutionary alliance had promoted a common revolution, but they simply adopted a moderate or radical approach, respectively.

Christian involvement

‘Chinese missionary and family,’ 1900. City of Vancouver Archives, Paul Yee, AM1523-S6-F58

Chen said that Chinese Christian churches in North America “had complicated relations with CERA from its beginning.” By the time Kang Youwei established CERA in 1899, “the Canadian Methodist Church had already conducted missionary work among the Chinese in British Columbia for decades.” Presbyterians followed suit in the 1880s.

“Both Christian groups would clash with CERA through their own reforms,” Chen said. A key issue was the fact that Kang wanted CERA to adopt a slogan he had used before: “protecting China’s nation, the Chinese race and the Confucian religion.” Kang backed off when Christians protested his religious proclamation, but the issue continued to simmer:

Chinese Christians in Canada gradually split with the CERA under Kang Youwei’s leadership, but they still followed his reformist precedent. In Vancouver, two Methodist ministers, Chen Yaotan and Feng Dewen [received help from others] in starting a Christian newspaper, Hua-Ying ribao (Chinese-English daily) in 1906.

Under Kang Youwei’s influence, they launched this Christian newspaper not only to preach the gospel, but also to advocate the reformist goals of combating gambling, opium smoking and similar vices among the Chinese migrants.

But Chen also wrote about the shift from reform to revolution:

Most Chinese Christians in the United States and Canada did not join Sun Yat-sen’s party, but many were supportive with revolutionary propaganda and mobilization through their radical reforms or institutional clashes with CERA under Kang Youwei’s leadership.

Sun Yat-sen himself was a Christian. He was baptized in Hong Kong in 1883 after being introduced to Christianity in Hawaii. Chen wrote, “As a Christian, Sun was able to secure one night of lodging in each of the Methodist churches in Vancouver, Nanaimo and Victoria.”

Zhongping Chen’s publications include four books, two co-edited bibliographies, more than 60 journal articles in English and Chinese, as well as works on two websites, Victoria’s Chinatown: A Gateway to the Past and Present of Chinese Canadians and the Chinese Canadian Artifacts Project. He has just finished a new book manuscript, ‘The Transpacific Chinese Diaspora in Canada: From Origins to Rise and Reform, 1788-1898.’

Go here for a very interesting in-depth story by Christopher Cheung about Yip Sang and a big Yip family reunion in Chinatown last July.

The ‘Victoria’s Chinatown’ site has a page devoted to Kang Youwei and another to Sun Yat-sen.