British Columbia residents are slightly more likely than fellow Canadians in other provinces to “reject religion,” according to a new and comprehensive public opinion poll from the Angus Reid Institute. And folk in Saskatchewan, Manitoba and the Maritimes are somewhat more likely to “embrace religion.”

British Columbia residents are slightly more likely than fellow Canadians in other provinces to “reject religion,” according to a new and comprehensive public opinion poll from the Angus Reid Institute. And folk in Saskatchewan, Manitoba and the Maritimes are somewhat more likely to “embrace religion.”

The poll explores Canadian views on religious belief, faith and multifaith issues. It reveals that a “solid core of Canadians continues to embrace the Christian faith and other religious traditions.” And it indicates that part of that continuing embrace is based on the relatively strong religious impulses on newer Canadians coming, often, from various parts of Africa and Asia.

The survey also provides some religious contrasts between BC and the east coast of Canada:

Regionally, the two coasts offer a lot of contrast. BC residents give consistently lower ratings to the Christian groups assessed, and save their highest for Buddhists. Atlantic Canadians give relatively high marks to the Christian groups and (along with prairie dwellers) are much more wary of atheists. Quebec is exceptional for the relatively lower ratings assigned to Muslims, Sikhs and Jews.

In taking and publicizing the poll, Angus Reid continues its periodic analysis of Canadian religious attitudes and practices, begun several decades ago. The polls have not only assessed the nature of religious life but tested its intensity in various settings.

In a news story about the new Angus Reid poll, Maclean’s magazine’s Aaron Hutchins, in its March 26 issue, prefaced his report with quotes from University of Lethbridge sociologist Reginald Bibby. In ‘Religion isn’t dying. It may be rising from the grave,’ he reported that 22 years ago, in his book Unknown Gods, Bibby:

. . . painted a rather dreary picture of where Canada’s churches would be by about 2015.

Congregations would be older, birth rates wouldn’t keep up with the number of folks who were dying off, and all the while many children weren’t being socialized into a faith. It was a linear decline, plain and simple. The writing was on the wall.

But, today, Bibby attests that immigration has made the difference between Canadian Christianity dying and rising again, so to speak. He told Hutchins:

Catholics, for example, are building new churches in some parts of the country. Evangelicals increased their total numbers as Canada’s population grew. The same goes for Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists and Sikhs. He had accurately forecasted a long, drawn-out decline for the United Church of Canada and the Anglican Church. But some religions were getting an infusion of new blood.

What I screwed up on – it sounds so naive looking back – [is] I didn’t allow for the immigration variable. The thing that pumps new life into religion in Canada has been this mammoth entrance not only of Muslims, but also Catholics. Not to mention the Protestants, Sikhs and Hindus.

Hutchins also quoted Rick Hiemstra, research director for the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada, with respect to the immigrant effect on various parts of the Canadian Christian scene – past and present:

Evangelicals are holding their own by consistently hovering around a 10 per cent share of the country’s population. About 24 per cent of those evangelical affiliates are immigrants, [according to Hiemstra]. “We have a lot of immigrants [in the fellowship] because a lot of the churches are founded by different waves of immigrants,” he says. “I’ve got a list in front of me of over 200 denominations in Canada.”

Hiemstra explains that it was Dutch immigrants after the Second World War who founded the Christian Reformed Church. “Nowadays,” he says, “you’re getting denominations that tend to be smaller but very fast growing. They’re Chinese or African in origin – or South American or Korean or Filipino or Vietnamese.” Immigrants aren’t just joining churches; in some cases, they’re starting them. “It’s difficult even for a researcher like me to find and track them,” adds Hiemstra. “In many cases they won’t even show up as registered charities because they’re too new to have gotten around to applying.”

In recent months, Douglas Todd, religion/ethics/spirituality writer for The Vancouver Sun has described some of the Korean immigration scene as it relates to the church in Vancouver and the Fraser Valley. In a March 2, 2014 The Search blog, he wrote about the 3,000-strong Grace Community Church, a Korean congregation (one of about 200 in Metro Vancouver) located near the King George SkyTrain station in Surrey. He said:

This kind of evangelical Christianity – morally conservative and often charismatic – is the faith of choice for one out of two of Metro Vancouver’s more than 70,000 ethnic Koreans, a population that includes 15,000 foreign students. . . .

Don Baker, a Korean studies professor at the University of B.C., says many Korean migrants to B.C. experience cultural comfort by joining congregations like Grace Church, which has 3,000 members.

Along with dozens of other evangelical Korean churches in Metro, Grace each week sends a team to Vancouver International Airport to greet bewildered newcomers from Korea. . . .

UBC’s Baker said people join Korean churches in Canada, including Catholic ones, to feel more secure, strengthen their Korean identities, make business and social connections and take language classes in English, or, if they have been raised in Canada, Korean.

As a result, Christianity is even more popular per capita among Koreans in Metro Vancouver than it is in South Korea, where one out of three people are either Protestant or Catholic.

The Angus Reid study points out that:

The life-blood of previously dominant United, Anglican, Presbyterian and Lutheran denominations was immigration from Britain and Europe.

But as immigration patterns have shifted, so too has growth in different religions. With greater immigration from Asian countries in particular, the greatest increases have been among Roman Catholics, evangelical Protestants, and other major world faith groups.

The Maclean’s article says immigration is not being kind to the mainline churches, but neither is it a magic bullet for Catholics or evangelicals:

“The reality is that groups depending on natural increase are dead in the water. There’s just not enough people being born to offset the number who are dying,” Bibby says. “If you have stock in the United Church or the Anglican Church, Presbyterians or Lutherans, you’re going to lose a lot of money.”

Despite the good news that immigration offers, religion isn’t in the midst of a Hollywood comeback story. “There aren’t enough immigrant Christians to make up for the vast majority of Canadians who have become less enthusiastic, indifferent, or even hostile to Christianity,” says John G. Stackhouse, a professor of theology and culture at Regent College.

The findings of the new Angus Reid study are presented in three broad sections: “Religious Pluralism and Polarization”, “Religion a la carte” and “Topical Findings.”

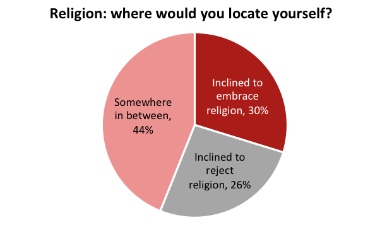

It shows three categories of attitude toward religion: those inclined to embrace religion (30 percent), those inclined to reject it (26 percent) and those in between (44 percent). The “rejecting” group appears to be growing a little faster than the other two categories and, according to the pollster, the shift from “embrace” to “in between” is more than just a trickle.

The study suggests that the in-betweens “still hold many conventional beliefs and sometimes engage in religious practices, including occasional religious service attendance. They do not see themselves as particularly devout; but they also have not abandoned religion.”

On a selection of other matters, the survey notes:

Across educational strata, we see consistent overall attitudes towards the main Christian groups assessed – except for Evangelicals who receive lower ratings from university-educated Canadians. This more educated group tends to feel more positively about the non-Christian groups assessed and towards atheists as well.

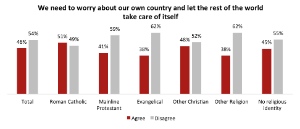

Evangelicals and members of other (non-Christian) groups tend to be more “internationalist” in their outlooks than mainline Protestants or Catholics.

Evangelicals and members of other (non-Christian) groups tend to be more “internationalist” in their outlooks than mainline Protestants or Catholics.

From the “religion-a-la-carte” sector of the survey report comes this observation:

Canadians may not be as inclined as they once were to adopt religion as a total package, complete with conventional beliefs, practices, and teachings. That said, the Angus Reid Institute poll reveals the majority of people across the country nonetheless continue to hold on to religious bits and pieces, picking and choosing from a wide range of items that are available in a lively spiritual and religious marketplace.

The full survey results are available on the Angus Reid Institute website.

As is required by law, Angus Reid has stated the methodology of its survey. It is:

The survey was conducted online from March 4-11, 2015, among a national, randomized and representative sample of 3,041 Canadians who are members of the Angus Reid Forum. For comparison purposes, a probability sample of 3,000 would carry a margin of error of +/- 1.8 percentage points, 19 times out of 20.