Nora Hendrix, pictured here with her husband Ross, was a key figure in the Hogan’s Alley community. Photo: City of Vancouver Twitter

Yes, Nora Hendrix is Jimi Hendrix’s grandmother. But that’s not why the City of Vancouver announced February 1 that a new temporary modular housing development at 258 Union Street will be named after her.

Hendrix was a key figure in the Hogan’s Alley community, which thrived in the Strathcona neighbourhood from the early 1900s – when many members of Vancouver Island’s black community moved to this area – until it was destroyed to make way for the Georgia Viaduct in the late 1960s.

Hendrix is particularly known for her role with Fountain Chapel, which was the centre of cultural life for the black community. Her legacy will no doubt be noted this Sunday (February 24) at the Grand Reopening and Celebration of African Fountain Chapel Vancouver.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the church which was central to the African-descent community in Vancouver for decades, until it was sold to Basel Hakka Lutheran Church in 1985. That history will be marked by a walking tour and the church celebration:

* Walking Tour: 11 am – 1 pm (starting from 897 Keefer Street)

* Celebration of Fountain Chapel: 2 – 4:30 pm (at 897 Keefer Street)

A recent article in The Star Vancouver said this about Nora Hendrix:

An image of Hogan’s Alley from the Portland Housing Society’s Instagram page.

Hendrix moved to Vancouver from Seattle after her husband Ross had found work in the city, and lived in Hogan’s Alley from the 1920s up until it was destroyed in the late 1960s.

She helped to start the first Black church in the area, and was also a cook at Vie’s Chicken and Steak House, which hosted many of the biggest musical acts of the time, such as Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong.

Now, a new building at the former site of Hogan’s Alley will bear her name. Nora Hendrix Place at 258 Union Street will have 52 units of temporary modular housing, the city of Vancouver announced [February 1]. The building will be run by the Portland Hotel Society and have a focus on supporting marginalized groups experiencing homelessness, while also including design elements shaped by Black culture.

The development will be part of the Northeast False Creek Plan which will revitalize the Hogan’s Alley area into a larger cultural site for the Black community.

Nora Hendrix when she did her Opening Doors interview.

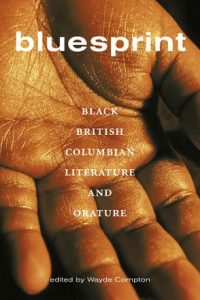

Wayde Compton devoted several pages to Nora Hendrix in Bluesprint: Black British Columbian Literature and Orature. Though he was unable to find any written accounts by a black person during the Hogan’s Alley period, he did include several interviews with community elders transcribed by Daphne Marlatt and Carole Itter in their Opening Doors: Vancouver’s East End.

Here is a portion of the Hendrix interview:

When I came there was no church. What few coloured people were here had some kind of little club, you know, that they used to gather and have a little affair, like, meeting and singing and whatever they did. They used to have it down on Homer Street, was a hall there, they had that going when I came here.

Them fine years different people was coming from Alberta. There wasn’t very many come direct from the States like I come, right just crow-flying like that. Of course, there used to be different little people, missionaries, come through, but they’d always get some little store place or something, you know, rent it, and have a little church or something like that.

The original home of Fountain Chapel, at Prior and Jackson, now no longer used as a church.

But nobody had ventured out to try and get a church for their own. They commence getting together, say, “Well, we should get a church of our own.” Yeah. “Ain’t got any other business of our own, so got to get a church anyway, if nothing else.”

So, let me see, it could be back in 1918, as far as I can think back, when we first taken that church over on Jackson Avenue.

I don’t know who had it before, but when we saw that we could be able to get this church, well everyone then started in, working together. All the families and everybody that wanted a church, we all got together, and commence working for it to get this church started.

And some of the men, they intercede and got a hold to the high-ups in the States, and they always from the States, we got all our preachers and residing elders all come from over in the States. That’s where the head office of that church was, the AME [African Methodist Episcopal] it was called. So then we got together and so they said, “Well, if you raise $500 we’ll raise $500.”

Pastor Andrew Mutuma (left) and Yasin Kiraga Misago of Fountain Chapel have organized the celebration.

So all of the sisters and brothers and everyone, we commence getting busy then, to start to having entertainments and bazaars and suppers and everything we could have, to raise the money to buy this church.

So when we worked around and got our share of money together, well, they let the residing elder know that we was ready, and so they came over and set up our church, so then we had our church then. So it was $1,000 we had to pay down.

In another Opening Doors interview from Bluesprint, Dorothy Nealy said:

Fountain Chapel was really the whole hub of this ghetto. If you wanted to meet anyone, the thing to do was to go to church. And that little church would be just packed to the doors. They had a beautiful choir. . . .

Fountain Chapel was really the whole hub of this ghetto. If you wanted to meet anyone, the thing to do was to go to church. And that little church would be just packed to the doors. They had a beautiful choir. . . .

It appears you can still buy Bluesprint from Vancouver publisher Arsenal Pulp Press, and there are several copies available in the Vancouver Public Library.

With a wide variety of selections from more than 40 people – beginning with Sir James Douglas, the second Governor of BC – this book would be a revelation to most local residents.

For a detailed blog history of the church by James Johnstone – which suggests some of the dates may be slightly different from those remembered by Hogan’s Alley residents in later life – go here.

Johnstone offers regular History Walks in Vancouver; if you can’t make the February 24 tour, his next scheduled walks for East End / Strathcona are February 23, March 9 and March 23.

[…] an interview, Hendrix recalled that “all of the sisters and brothers and everyone, we commence getting […]