Wesley Hill will address the topic When Christians Disagree during a livestream talk July 29. He is teaching Male and Female in Christ as part of Regent College’s Summer School.

Wesley Hill will address the topic When Christians Disagree during a livestream talk July 29. He is teaching Male and Female in Christ as part of Regent College’s Summer School.

Pursuing sexual purity by turning toward the other

I remember a day several years ago, when I was training for ministry, that I sat around a table and talked with a group of Christian friends, all male, about lust. One of the men was a pastor at the church where we were all members.

As we discussed various ways of trying to practice “custody of the eyes,” the pastor made a statement to this effect:

No one would be tempted by lust if you were standing in front of the Grand Canyon right now. Or in front of Bridalveil Fall at Yosemite National Park. The splendor and grandeur of those places would be so overwhelming that you’d turn from fantasizing to wonder at their beauty instead.

This was meant, I think, as a strategy: Learn how to crowd out whatever fascination with an image of a human you’re nurturing with something more overwhelmingly fascinating.

At the time, that comment struck me as . . . let’s just say highly unworkable. It still does. As much as I love nature – I spent much of my high school years hiking and camping in the Rocky Mountains of New Mexico and Colorado, and I consider Yosemite to be the most jaw-dropping instance of natural majesty I’ve ever had the good luck of witnessing – nothing holds my fascination like the human form.

I thought of all this again when I read a tweet from another pastor, Vito Aiuto, recently:

I’ve climbed Machu Picchu in Peru, I’ve visited the Parthenon in Rome, I’ve watched it snow in deep woods in rural Michigan, but nothing is as beautiful as a human being. – Thomas Vito Aiuto (@ThomasVitoAiuto), January 12, 2018

If that’s true for more people than just Aiuto and me, our strategy for resisting sexual temptation has to look pretty different than what my pastor was recommending, doesn’t it?

When the temptation comes to nurture fantasies that cannot be rightfully fulfilled, to treat others as mere objects for our titillation, even if only in the privacy of our thoughts – when the desiring gaze lingers “like a slug on a rose,” in Cyrano de Bergerac’s yucky phrase – surely the answer cannot be to start trying to picture boulders and forests and creeks instead. That sounds to me like a counsel to fight a conflagration with thimbleful of water.

In an essay on the lure of pornography and how one might say no to it, theologian Jason Byassee [who teaches at Vancouver School of Theology] wrote this:

Christians have resources with which to aid [the] recovery of genuine eros, though they’re a bit dusty at present. I think here that Orthodox iconography, when done right, is beautiful beyond words. It had better be: Worship bears the Church up to heaven into the presence of God. Liturgy is a drawing out of our true selves, our best selves, in union with God in reflection of God’s union with us in Christ through the Theotokos. It’s erotic in a chaste sort of way. . . . But how does it work? Surely it’s more complicated than giving a horny kid an icon and teaching him how to pray before it. . . . Or is it?

. . . A friend of mine likes to say that the Christian answer to pornography is soup kitchens. All our senses are engaged there in community with others for the sake of serving Christ in the poor. What could be more erotic? That is, what more could draw us out of ourselves toward another?

The challenge, it seems, isn’t really the replacement or the eradication of fascination with the human form (as if that were possible) but its redirection. “We have these parts, these desires, for a reason,” is how Byassee’s essay ends: “to love and be loved by God.”

I think I know – or I think I’m learning – what he means.

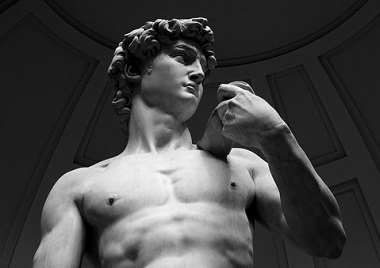

Years after that Christian roundtable on lust, on my first trip to Italy, I found myself wandering museums and taking in dozens of nude sculptures and paintings. The Berninis at the Galleria Borghese, the Michelangelos: it wasn’t just the pagans who crafted the human body. Many of these nudes were Christian. Clearly, these were artists captivated by the human.

As Marguerite Yourcenar’s elegiac Hadrian muses:

In Egypt I have seen colossal gods, and kings; on the wrists of Sarmatian prisoners I have found bracelets which endlessly repeat the same galloping horse, or the same serpents devouring each other. But our heart (I mean that of the Greeks) has chosen man as its center. We alone have known how to show latent strength and agility in bodies in repose; we alone have made a smooth brow the symbol of wise reflection. I am like our sculptors: the human contents me; I find everything there, even what is eternal.

Hadrian was no Christian, but it’s a short leap from what he says here about the greater beauty of the human form above nature to classic Christian articulations of the imago Dei. The wonders of nature are hymned in Scripture, yes, but the highest paeans are reserved for humanity. “Yet you have made them a little lower than God, and crowned them with glory and honor” (Psalm 8:5).

That’s why it doesn’t work for me to try to resist lustful imaginings by turning from the human to the inanimate creation. Granted, sometimes it’s best to leave the house and go for a run. But the ultimate way to do battle with sexual temptation can’t be to turn away from the human; it must be to struggle for a kind of purified gaze, to try to rediscover what erotic desire is for in the first place.

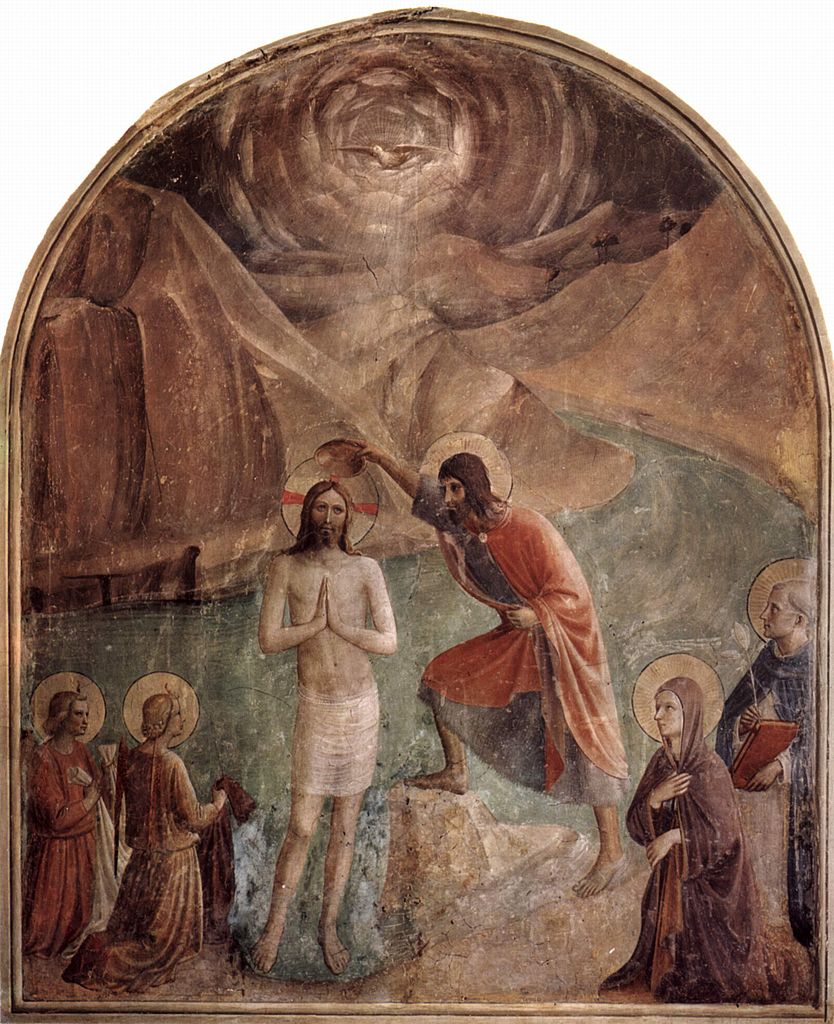

My trip to Italy ended in Florence, with a visit to the San Marco cloister. Inside each of the monks’ cells there’s a scene from the life of Christ painted by Fra Angelico. It was interesting to notice how the usual touristy hubbub died down once people stepped into the cloister and paused at each of the cells’ doorways to look at the frescoes.

A hush fell. I’m not sure I’ve ever seen such obviously devotional art. These meditative pieces by Angelico seemed as if they were born from a kind of holy attention that I haven’t encountered before in quite that way. It was affecting, and I paid the museum fare a second day just to have more time with this art.

Fra Angelico’s Baptism of Christ (circa 1438–35), Museo di San Marco, Cell 24, Florence, Italy

All of the frescoes were, of course, dominated by human figures: Jesus above all, but also Mary, Peter, James, John, Mary and Martha, Moses and Elijah, the Magi, and others. Painting with Christian devotion, in other words, didn’t mean for Angelico a turning away from the human form. Just the opposite. He was one of the first to exemplify what would become commonplace in Renaissance art: an exquisite attention to the expressions of emotion and personal particularity.

Here’s what I’m trying to gesture towards, I think: Chastity isn’t about turning away from the human, refusing to meet the eyes of others out of fear of temptation or contamination. Resisting sexual temptation – or, putting it positively, pursuing the ascesis of sexual purity – is instead about turning toward others in a love that’s no less real for not resulting in sex.

Dr. Wesley Hill

And it can be breathtakingly beautiful. Indeed, it can lead, as it obviously did in this instance, to some of the most wonderful artistic expression our culture has. It can be done with such compelling power that it makes even a group of jaded tourists fall silent.

This article was originally published in the Spiritual Friendship blog, and is re-posted by permission.

Wesley Hill is Associate Professor of Biblical Studies at Trinity School for Ministry, Ambridge, Pennsylvania. His most recent book is The Lord’s Prayer: A Guide to Praying to Our Father.

If you’re considering taking his course, you could listen to his Asceticism in the 21st Century podcast.