Burrard St. Story Guild kids offer a closing blessing to audience: “May your story be woven into God’s Story.” Photo: Abigail Balisky

It’s commonly assumed that the taking of a breath is the first thing we do outside of the womb. Research, however, indicates that on average it takes a full 10 seconds before a newborn takes their first gulp of air.1

So if taking a breath is not the first thing that happens to us at birth, what is? Answer: We are caught and held in the hands of another.

Other animal species drop from the birthing canal (eg. calves and foals) or slide to the ground (eg. puppies and kittens) unattended. In contrast, human infants are uniquely dependent on an attending other to catch them, indeed without whom they’d risk serious injury or death.

A spiritual quest

After 30-plus years as a pastor and storyteller I’ve developed a theory that spiritual questing is, at least in part, an attempt to recover that first sensory out-of-womb experience.

Of course, having our full weight born up by another gets increasingly difficult as we age. By four or five our primary caregivers go on strike, protesting that we are too heavy to be carried. Understandably they coach us toward full independence when it comes to carrying our own weight.

Still that doesn’t keep us from the primal longing and, in time, we turn to peers – a first boyfriend, a girlfriend, a best friend, a lover, a spouse.

The wildly popular children’s book, Love You Forever by Robert Munsch captures the sentiment well. It begins with a mother holding her newborn son and ends with the son holding his dying mother. With 37 million copies of the book sold worldwide, it would seem the longing to be held is not only universal, it spans the breadth of a lifetime.

A children’s picture book can make it look simple. In reality, the weight of our being is a lot for another to carry. We grow heavy, and not just physically. Chances are the greater heft comes from what we carry around inside, especially those of us who have grown up in a culture that leaves it up to the individual to secure his or her own sense of self-worth, safety and belonging.

Perhaps the best indicator of this inner weightedness, already measurable in pre-adolescence, is the oft-cited rise over the past 20 years in childhood and teen anxiety and depression.

“In addition to the social isolation and academic disruption [from the pandemic] that nearly all children and teens face,” writes Zara Abrams of the American Psychological Association, “many also lost caregivers to COVID-19, had a parent lose their job or were victims of physical or emotional abuse at home.”

“All these difficulties, on top of growing concerns about social media, mass violence, natural disasters, climate change and political polarization – not to mention the normal ups and downs of childhood and adolescence – can feel insurmountable for those who work with kids.” 2

Anyone who has tried to reassure an anxious child knows something of this weight. We hold our children close and tell them everything is going to be okay. Yet our hugs hardly scratch the surface of the inexplicable fears they carry around inside.

What we want is to tell them that they don’t need to carry the burden of themselves or the world alone. What we want is to tell them to let go.

But the question is, what do they let go to? It’s not clear.

Kathy’s story

A middle-aged woman from our church recently shared her spiritual journey with a group of teens considering confirmation. Kathy described growing up in an on-again-off-again church going family and how she left home as a young adult feeling no attachment to any of it.

She traveled widely, wandering in and out of eastern spirituality until she finally abandoned the spiritual quest altogether in favour of a strictly secular lifestyle. She described being clear with the officiant at her wedding that she didn’t want any scripture readings and that no mention of God was to be made.

“The following decade,” Kathy continued, “I can honestly say I was perfectly happy and wanting for nothing. Then one day I went back to church with my young daughter. I thought it would be good for Evie to be in touch with this part of her cultural heritage. We entered the sanctuary with its other-worldly stained glass windows depicting stories of Jesus that I hadn’t thought of for years. I wondered how it would impact Evie, but as it turned out it wasn’t Evie who was impacted. It was me. I couldn’t stop crying.”

When asked what made her cry, Kathy said she didn’t know. That she couldn’t put her finger on it.

But I have a theory: I think she felt held. I think that after years of going it alone she could simply let the full weight of her being go, and know that she was held.

When my story is held in God’s story

I have long contended that the purpose of a sacred story tradition is to hold us. To hold the world intact so that we can let go. No one wants to be left holding their own story.

Burrard St. Story Guild kids as ‘friends’ of Job, accusing him of wrongdoing. Photo: Abigail Balisky

Twenty-five years ago I started a theatre arts program called Story Guild where children and youth use drama, music and choreographed movement to explore and tell the stories of the Jewish and Christian scriptures. The story guild tagline is ‘Where my story and God’s story meet.’

Having told countless numbers of children countless numbers of Bible stories over the years I can attest to a simple phenomenon. That when children understand there is a Story out there bigger than their own story and that they don’t have to carry their story alone, physical tension leaves their bodies. I watch as their faces soften and their shoulders drop an inch.

The format is not complicated. We sit together on the floor in a circle, the participants ranging in age from seven to 17. There is nothing between us – no printed curriculum, no pictures, no worksheets, no crayons, no fidget toys, no screens.

Just me holding a Bible that I’ve described at the start of the season as a book with old, old stories passed down for generations until they have been passed down to us. Now we are the custodians I tell the kids. And the reason stewarding and passing on these old stories is so important is because they are not our stories. They are God’s stories.

On this particular day I tell the story of Job to the dozen or so participants who make up the Burrard St. Story Guild at Canadian Memorial United Church. I don’t read it. I just retell the story, in my own words. I don’t layer on doctrine. I don’t glean a lesson in morality.

The kids lean in as kids will when a story is told from the heart.

I stop at the point where Job is on the defensive, feeling unfairly accused of doing things he didn’t do or of neglecting to do things he did.

I ask the kids if any of them can relate. The hands shoot up.

“My mom never listens when I say I’ve already practiced piano,” one child huffs, her arms crossed and brow furrowed. “She makes me practice again. She never believes me.”

Another describes how a fellow classmate intentionally tripped him, causing him to knock over a fellow classmate’s lunchbox. “It wasn’t even my fault, but the teacher blamed me.”

The stories carry on in this vein, each one ending with some variation of “it wasn’t fair.”

After each participant shares their story, the rest of the group is ready with a shared response. The response doesn’t attempt a solution, it is not vindication, it’s not even empathy. It’s simply a prayer and it is always the same:

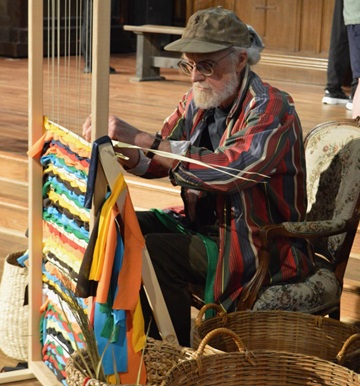

God depicted as a weaver in Burrard St. Story Guild’s retelling of the Job story. Photo: Abigail Balisky

“Thank you God that (inert name)’s story is held in Your Story.”

The kids feel the significance of this prayer. The reason I know it’s visceral is because if it gets missed after any one child has shared, they are quick to point out the oversight.

At the end of the season the kids of the Burrard St. Story Guild offer their own, artistically rendered telling of the story of Job to a packed sanctuary during the Sunday morning service.

Through music, dance and drama, they embody the story of a man who, in the final scene, falls to his knees after glimpsing God face-to-face and relinquishes his need to justify his own life.

This story is now in their spiritual DNA. They will carry it with them for life and it will be there for them when they need it.

A swan-feather cloak

Renowned mythologist and oral storyteller, Martin Shaw, says “If you don’t have stories wrapped around you like a swan-feather cloak, the old Irish idea is that you will be prone to enormous bouts of anxiety as you get older.”3

“Kids need mythic ground to stand on so when the world comes at them, they’ve got a little push back.”

My firstborn, Aden, was born at full term but for unknown reasons his lungs failed to clear of fluid. While he never took a breath the monitor continued to track a heartbeat until it went silent. Aden was registered as a live birth. The span of his life? 19 seconds.

Back in my hospital room the doctor came in to see me. She was visibly shaken and quick to offer potential explanations.

But I wasn’t interested in explanations. I asked to see her hands.

She looked at me apprehensively then raised her hands from her lap. They were beautiful to me.

“You held my son,” I said.

That was enough. To know Aden had been held, if only for a moment. It was all I needed.

Maybe, in the end, that’s all any of us need.

1 https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/002395.htm#:~:text=At%20birth%2C%20the%20baby%27s%20lungs,change%20in%20temperature%20and%20environment

2 https://www.apa.org/monitor/2023/01/trends-improving-youth-mental-health

3 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uqq9jEJpaww

Tama Ward

Tama Ward is an ordained minister, storyteller and educator who has led story guild programs in Canada, Mexico and Kenya with children and youth from Protestant, Catholic and Muslim backgrounds. She currently serves as the Minister of Children, Youth and Families at Canadian Memorial United Church in Vancouver, home to the Burrard St. Story Guild.

Tama lives in New Westminster with her husband of 27 years, Loren Balisky, and her two university-aged children, Abigail and Oliver.

She has written this comment as a member of The Bell: Diverse Christian Voices in Vancouver.

Wow. Thank you for this beautiful, moving and vulnerable piece.