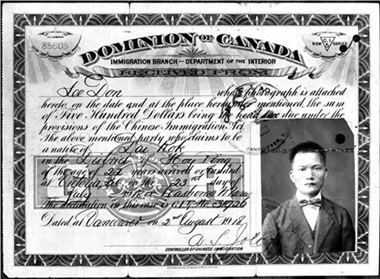

This head tax certificate was issued to Lee Don in Victoria July 23, 1918. (VPL 30625)

Recent news headlines show that we are living at a time of heightened backlash against immigration. Anti-immigration anxieties have animated political forces around the world and immigrants are regularly scapegoated for all kinds of social problems, especially on social media.

While the economic and social effects of immigration are complex and nuanced, what is usually taken for granted is an instrumental view of immigration – that immigration must first and foremost serve the interests of the ‘host’ nation. But who defines these interests and how?

For those of us on the west coast of what is now Canada, these are deeply fraught questions. Immigration, after all, was the primary means to create a settler colonial society through Indigenous dispossession (Canada used to have a Department of Immigration and Colonization, the name of which starkly reveals the purpose of immigration).

Immigration policies have always been about choosing the ‘right’ kinds of people to admit and for the first hundred years of Canadian history, immigration policies were designed to overwhelmingly favour white settlers over other racialized groups.

Chinese head tax

Among the many instances of discrimination in Canadian immigration history, few were as destructive as the Chinese head tax. Chinese started coming to the west coast in the late 1850s, and were almost immediately subjected to systematic discrimination, exploitation and even violence.

Widely disdained and denigrated, they were accused of taking economic opportunities from the ‘right’ kinds of settlers. The federal government waited until the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railroad, which involved thousands of Chinese workers, to introduce a head tax that was targeted at Chinese only.

Between 1885 and 1923, almost all Chinese coming into Canada for the first time had to pay a punitive tax that was initially set at $50 before rising to $500 by 1903. The government presented the head tax as a means to curb Chinese immigration, but on this count, the head tax was a failure: Chinese continued coming as long as economic conditions allowed.

Source of revenue

In practice, the head tax entrenched a debt-based system of labour migration that relegated Chinese workers to low wages and exploitative work conditions. Until the mid-20th century, most Chinese immigrants were men who were searching for employment opportunities in order to support their families back home.

Most had to borrow money to pay for their passage across the Pacific and other related costs, with the expectation that they would repay these debts from their future earnings. Loans were often obtained informally from immediate and extended family networks, with a variety of conditions when it came to repayment and interest.

The head tax drove up the cost of immigration astronomically, but as long as jobs were available Chinese immigrants took on ever larger debt loads – and the risk that their journeys would eventually pay off.

Thus, instead of curbing Chinese immigration, the head tax simply turned immigrants into a direct source of revenue. Until 1918, Canadians did not pay income tax, a policy that was explicitly designed to attract more desirable immigrants. As a result, the head tax played an outsized role in public finances. At its height, the $500 head tax was equivalent to about two years of wages. Canada collected about $23 million from 82,000 arrivals, roughly equivalent to $1.2 billion today.

Since revenues from the head tax were split between the federal and provincial governments, British Columbia – where the majority of Chinese immigrants entered and lived – was its main beneficiary at a crucial period in the province’s development. In other words, other residents of BC, and by extension those who live here today, were and are beneficiaries of the head tax, albeit in very unequal ways.

Heading south

Even as Canadian authorities regularly used racist and incendiary rhetoric against Chinese, their policies allowed them monetize Chinese immigration. Ironically, one of the reasons for the head tax’s ‘success’ is that a large proportion of Chinese immigrants had no intention of staying in Canada.

According to estimates around the turn of the century, up to half of new arrivals were actually headed towards the United States, where an immigration law imposed in 1882 excluded practically all new Chinese immigration. Looking for alternatives, many Chinese landed in Canada, paid the head tax, and then slipped across the sparsely guarded border. Authorities in the United States routinely complained that Canada profited from the head tax even though they were the ones who had to deal with the ‘illegal’ immigrants south of the border.

Low wages, debt, insecurity

Beyond tax revenues, the continual arrival of Chinese immigrants fed into an ongoing demand for their labour. In essence, Chinese workers were made to pay for their own exploitation. In BC’s resource-dominated economy, the presence of a cheap, mobile and flexible workforce was critical for industries such as fisheries, farming, mining and public works. Chinese received much lower wages than white workers and had little access to social welfare and other supports despite experiencing much more job insecurity.

Because the head tax resulted in higher debt loads, Chinese needed to maintain steady employment despite steep employment discrimination. Another consequence of the head tax was to reinforce the power of labour contractors, who were usually Chinese themselves and acted as middlemen between employers and workers.

Some contractors were even directly connected to the lenders who financed immigrant journeys in the first place, placing additional pressure on immigrants to fulfill their debt obligations. The toxic combination of debt, employment precarity and surveillance proved crucial in maintaining Chinese as a ‘reliable’ work force.

‘Humiliation Day’

The head tax was not merely a financial penalty, but a fundamental part of an exploitative system that shaped all aspects of immigrant life. The fact that this system lasted for almost four decades provides a sobering reminder of how racism and discrimination, when enacted through the seemingly fair and objective language of law and administrative procedure, could operate so openly with relatively little push-back.

Even during its heyday, the injustices of the head tax system were not hidden. Numerous government commissions and reports documented the misery faced by Chinese immigrants and immigrants themselves frequently protested their conditions. Tragically, this information rarely resulted in calls to abolish unjust practices and compensate those who were affected. Instead, calls to get rid of Chinese immigrants altogether grew louder and louder.

When the head tax was finally repealed in 1923, it was replaced by an even more draconian exclusion act that, like its American counterpart, halted practically all new immigration. Ironically, the government presented outright exclusion as a means to rectify an ‘unfair’ head tax. But for Chinese immigrants and their communities, it was an outright catastrophe. July 1, 1923, the day the Chinese Exclusion Act came into force, became widely known as ‘Humiliation Day.’

Broken, bitter

Chinese across Canada protested these policies fiercely. But humiliation is, by definition, also an intensely personal experience, one that can affect successive generations even when the original source of humiliation is no longer here.

Chinese immigrants who paid the head tax not only lived with the awareness that they were unwanted in Canada (the signs of which were everywhere). More tangibly, they were saddled with large debts that they had to pay off even while trying to support their families at home.

Coming to Canada often meant years, even decades, of separation from their loved ones, including spouses and children (the head tax made it prohibitively expensive to bring family members to Canada). Debt obligations clashed with family obligations and other desires, which left many trapped in a system of injustice that made them physically, emotionally and spiritually broken.

In Judy Fong Bates’ powerful memoir The Year of Finding Memory, she recalls how her father – who came to Canada in 1914, paid a $500 head tax and spent the rest of his life doing the grueling work of a laundryman – remained bitter about his ordeal for the rest of his life. Fong Bates recalls his words: “Only the Chinese had to pay this money. No one else. Five hundred dollars to get into this country. Five hundred dollars I had to borrow.”1

International condemnation

It was not until 1947 that the 1923 exclusion act was finally repealed as Canada faced increasing international condemnation for its immigration policies. It took two more decades for the last anti-Chinese immigration policies to be removed, and many more years for head tax payers and their families to tell their stories and demand the recognition and redress rightly due to them.

For a long time, their voices were ignored or rejected by those in power who claimed that Chinese paid the head tax voluntarily and actually benefited from being in Canada. When the Canadian government finally apologized for the head tax in 2006, it only offered partial compensation to surviving head tax payers and their spouses.

Important lessons

Even though 2024 seems so different than 1885, the head tax continues to offer important lessons as we confront the current rise in anti-immigrant xenophobia.

What happens when entire groups of migrants are racialized, excluded, exploited and monetized? When immigration is primarily seen as a matter of economic utility, we lose sight of the fact that none of us, regardless of citizenship, are primarily economic beings.

Chris Lee

When we reduce immigration to what benefits our interests, we are saying that the lives most affected by our policies do not matter.

For communities that are committed, however imperfectly, to living out alternative value systems – including faith communities, educational institutions, community-based non-profits and so on – rejecting anti-immigrant xenophobia is about making space for a different way of being in the world and with each other.

1 Judy Fong Bates, The Year of Finding Memory: A Memoir, Random House Canada, 2010, pg. 5.

Chris Lee teaches Asian Canadian literature and culture at the University of British Columbia. He is currently working on a research project on Chinese Canadian family narratives from the exclusion period to present.

He has written this comment as a member of The Bell: Diverse Christian Voices in Vancouver. Go here to see earlier comments in the series.

As one of the three representing the BC Coalition of Head Tax Payers and Spouses to join others in 2006 to finalize Canada’s Head Tax Redress with the new Harper government, I am thankful to Chris Lee for chronicling a key piece of our shared Canadian history.

Yet left unclear in the article is the Christian connection with the ‘settler colonial society’ so that more Christians can be humbled by our role in the ‘host’ nations. Particularly for Christians with apolitical and ahistorical upbringings, the temptation is to dismiss such history as actions by sinners and we Christians are much better than that. Others may view it as a distraction to their church ministries or respond with “If my forefathers did that, what has that to do with me?” That was a young man’s exact question when I highlighted Canada’s unjust treatment of the Indigenous peoples at a Missions Fest seminar.

To help to connect the church with such history, one should realize the Catholic church over 500 years ago was complicit in legitimizing the enslavement of those of colour and the colonial expansion to their lands by European monarchs (re Doctrine of Discovery).

Though Martin Luther initiated the Protestant Reformation 25 years after the Pope condoned Columbus ‘discovery’ of the Americas, he failed to add the evil of colonialism to his 95 theses. So despite also some Christian church’s colonial role in the notorious residential schools and becoming a bad news to the Indigenous community, the Christian church has, by and large, remained unaware and unrepentant and rarely gone beyond verbal symbolic reconciliation to people of colour. It is as if their previous role in dispossessing other’s land, sovereignty and human rights are okay as long as they continue to share the Gospel with the victims.

We live in a province whose Premier Richard McBride declared in 1912 “British Columbia must be kept white . . . we have the right to say that our own kind and colour shall enjoy the fruits of our labour.”

In 2008, BC celebrated BC150, a yearlong celebration with 1,000 pompous events across the province. Within BC150’s website was the official history of BC showcasing only those of Anglo-Euro descent. There was no mention of any Chinese name, not even the word Chinese. It is as if the Chinese were not already labouring away in BC as early as 1778, or suffered the grave injustice as described in Chris’s article.

More shocking is after subtracting 150 from 2008, the resulting year 1858 was not 1871 when BC joined the Confederation, but the year when BC was declared a British Crown Colony. It is sobering to know we live in a province whose leaders have the audacity in 2008 to celebrate its 150th birthday as a colony, a feat seldom tried by the worst colonies!

As for those who try to distance themselves as beneficiaries of colonial expansion, we need to be reminded that BC’s revised Land Act 1875, in an effort to attract the ‘right’ kind of people, made large pieces of homestead land available to settlers free of charge, except for Chinese and native Indians. Such free land included at least 160 acres of land in Abbotsford, BC’s “Bible belt!”

For those who argue that one cannot change history, one should consider what one can change now. Looking at some more current megatrends, the United Nations has initiated a global movement to end colonialism since 1960, followed by instituting the International Decade for the Eradication of Colonialism four times since 1990, and set 80-plus former colonies free since its birth.

So why is it that most Canadian Christians are still unaware of such momentous global movement to release the captives and the oppressed? Or continue to shun the Indigenous people and others as the Jews did towards the Samaritans in Christ time?

Meanwhile other political entities are quick to exploit BC’s current unreconciled relationship with those of colour. Externally, the risen China has been exploiting the resentment among Canada’s diaspora towards Canada’s century long official discriminatory policies and the glass ceiling still encountered at work.

So more and more within the Chinese diaspora have become foot soldiers for China in Canada, as revealed in the ongoing Foreign Interference Commission. The Indigenous communities, as well as the Inuit’s, are also becoming targets for China’s undue influence via offers of investment money, which they will not get from Canada so handily. The mistreatment of them also became China’s argument that Canada has no moral high ground to criticize China’s treatment of the Uyghurs.

Lately China’s proxies here often conflate criticism of PRC with anti-Chinese racism in an attempt to silence all critics of China. Behind the above lies the danger not just to Canada’s cultural harmony, but a rising national security threat particularly to our north with the longest undefended coastline.

Internally, BC’s latest election results should put an added urgency to practice tearing down the wall between the Jews and Gentiles outside the church. Since not a few Christians have poured their support behind John Rudstad, who was propelled to sudden fame in a near extinct party simply by it bearing a similar name as the populist federal Conservative Party, is stewardship merely about achieving prosperity which he promised? Or about ‘certainty’ for the resource industries by ripping up the UNDRIP?

If Christians are following the ‘common sense’ of ignoring the global trend to decolonize and worship even the shadow of a populist party, does it not spell a crisis for our Christian worldview?