This holiday season afforded me a small reprieve from the fullness of everyday life to be with extended family – to rest, relax and spend some time engrossed in narratives other than my own.

This holiday season afforded me a small reprieve from the fullness of everyday life to be with extended family – to rest, relax and spend some time engrossed in narratives other than my own.

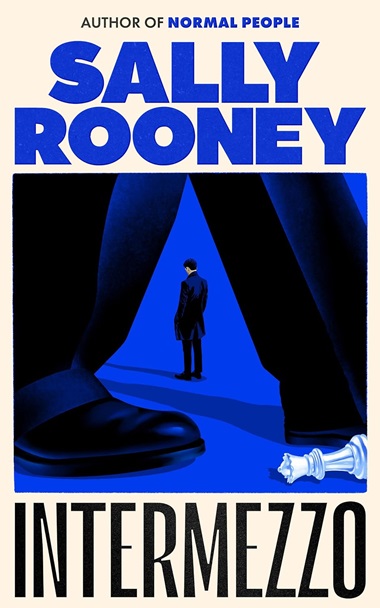

One story I’ve been looking forward to for months was Sally Rooney’s newest book, Intermezzo, which I purchased a couple of months ago from Massy Books after realizing I was 4000th on the VPL holds list.

I’ve been a fan of Rooney’s since reading Normal People several years ago. She’s been lauded as the voice of a generation and has a large following and I had a special interest in Intermezzo as I’ve just taken up chess.

Spoiler alert – for those hoping to increase your Elo or learning to play the London System, Intermezzo offers very little in the way of help.

However, what Intermezzo lacks in chess strategy, it more than makes up for in beautiful prose and articulation of the expanse and limits of modern life, specifically in relationships.

As often characterizes Rooney’s writing, the plot of Intermezzo takes a backseat to the web of relationships of seven characters: two brothers, Peter and Ivan, working through the grief of the loss of their father; Naomi, Margaret and Sylvia, Peter and Ivan’s significant others; and Christine, Peter and Ivan’s mother.

The novel is an invitation to explore the complexities of the inner and outer worlds of these characters. As Rooney writes: “The demands of other people do not dissolve; they only multiply. More and more complex, more difficult. Which is another way . . . of saying, more life, more and more of life.”

One of the fascinating things about Intermezzo is that it both takes for granted and at the same time challenges an assumption about relationships widely held in our culture. While personal relationships have always been central to human life and experience, in Rooney’s novels, relationships are more than important, they are the entire scope of the world, the whole stage on which the drama of life unfolds.

No larger story animates the narrative, just the relationships and cultural expectations that the characters may choose to live within or rebel against.

On one hand, the absence of a larger or cosmic narrative makes the characters ‘free’ to curate their life in any way they’d like, to create their own meaning, and to explore various ways to meet their need for love.

On the other hand, Intermezzo is clear about the massive amount of pressure on each individual to manufacture a life that will be meaningful enough, to become people who will be good enough, and to find ways of grieving that can match the depth of the losses they feel.

Towards the end of the novel, Peter’s internal monologue articulates this pressure. He’s been living his life “[a]s if attempting to reach the end of his desires, to find out what is there at the end. Discovering instead with horror that his desires even when instantly and gorgeously gratified only make him increasingly unhappy and insane. Wanting too much.”

This weight doesn’t just sit with the characters themselves, it affects everyone around them. Each relationship is both animated and shot through with the heaviness of expectation of people on each other. As one character says, “Sometimes you need people to be perfect and they can’t be and you hate them forever for not being even though it isn’t their fault and it’s not yours either. You just needed something they didn’t have in them to give you.”

For the most part, the imperfect relationships in the novel admirably bear the weight of these ultimate human concerns. The characters, specifically the female love interests, showcase the amazing human capacity for grace, forgiveness and, ultimately, a type of love and healing acceptance of their flawed partners.

Yet, one of the things I appreciate most about Rooney is her openness to the possibility of a larger narrative that might help carry the burdens we put onto ourselves and each other. Sometimes these wonderings become explicit, like Ivan who asks his girlfriend, “Do you believe in God?” or characters who feel compelled to pray. Often, however, they are more implicit, felt as an unfulfilled longing or the fleeting nature of pleasure.

John Hau

There are no simple answers, and there is no apologetic for the Christian faith within the novel, but I hope Intermezzo will encourage readers to consider searching beyond the immanent frame to meet the deepest longings of human life.

John Hau is lead pastor at Reality Church and the COO of Colours + Shapes, a multidisciplinary creative studio, both in East Vancouver.

He has posted this comment on this site as a member of The Bell: Diverse Christian Voices in Vancouver. Go here to see earlier comments in the series.