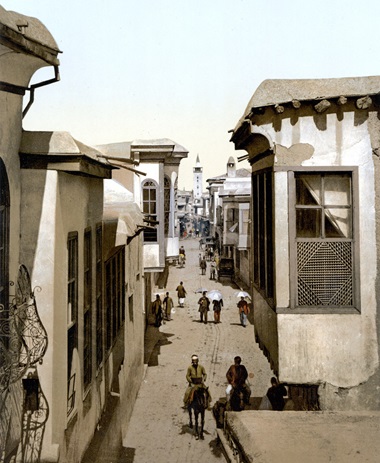

The Street Called Straight, Damascus, Holy Land, (Syria). Detroit Photographic Company, 1890 – 1900.

In the song ‘Straight Street,’ J.W. Alexander and Jesse Whitaker say, “Well I used to live on Broadway, right next to the liar’s house, my number was self-righteousness and a very little guide of mouth.”

This song is about conversion, a life turned away from the liar’s house and now lived on the straight path, the straight and narrow. It places conversion, that is, in the context of truth telling and turning from lies. So, does it matter if we tell the truth?

This is not that complex a question, not a trick question, and most people would say that it certainly matters, whether their position is based on a religious text – such as Exodus 20:16 (“You shall not bear false witness against your neighbour”) or the presentation of Satan as “the liar” (John 8:44) and God as incapable of lying (Titus 1:2) – or on an inherent or natural sense of what is right and how we ourselves want to be treated.

That is, just like most people know theft is wrong because they do not like their stuff being stolen, most of us adhere to the truth because we do not like people lying to us.

There is another related issue and that is the tone and content of what we say and its implications for others, either at a personal or community issue. This is when we say things intended to hurt others or to create animosity towards them.

This might be based on truths, partial truths, exaggerated truths or falsehoods, but the intent of this sort of speech is not to defend oneself, but to harm others. I think this sort of speech is in mind when the letter of James 3:8 says, “but no one can tame the tongue – a restless evil, full of deadly poison.”

In the lead up to the forthcoming election in the United States, a story took root about Haitian immigrants stealing their neighbours’ pets, dogs and cats, and eating them. Donald Trump even spoke of this at a Presidential debate.

This story now seems grounded in baseless rumors and lies. J.D. Vance, Trump’s vice presidential running mate, suggested on CNN, when challenged about the veracity of these claims, that “If I have to create stories so that the American media actually pays attention to the suffering of the American people, then that’s what I’m going to do.”

On September 9, Vance had claimed on X that “reports now show that people have had their pets abducted and eaten by people who shouldn’t be in this country.” On September 10, after local leaders said these were not factual stories, he said on X, “In the last several weeks, my office has received many inquiries from actual residents of Springfield who’ve said their neighbours’ pets or local wildlife were abducted by Haitian migrants. It’s possible, of course, that all of these rumours will turn out to be false.”

I focus on J.D. Vance’s words because as a politician, his words impact numerous people quickly, and because he identifies himself as a Christian and a Catholic. How he speaks matters because of his large audience: one of his tweets on X regarding this has over 15 million views.

Our words and speech have implications for real people. On September 12, a bomb threat was “sent to multiple agencies and media outlets” that “used hateful language towards immigrants and Haitians in our community.” The next day Trump repeated the false claim at a rally in Arizona, and in Springfield, Ohio two elementary schools were evacuated due to an email threat and a middle school was closed all day due to threats. But truth matters no matter how big or small our audiences.

Truth also matters regardless of how righteous we think our causes are – and Christians especially need to keep in mind that there is no exception, whatever our political beliefs, to the righteousness of truth.

Increasingly, truth is seen as insignificant if we can advance our own political parties and social or cultural issues and this is not just an issue in the United States, but in Canada and throughout the world. Christians need to take the lesson of James and rediscover that the truth and how we use our tongue to guide us is always relevant, the ground on which our integrity rests.

The writers of ‘Straight Street,’ written in the 1950s and first recorded by the gospel group The Pilgrim Travelers in 1955, knew how important telling the truth and speaking without rancor is to personal conversion. Ry Cooder recorded ‘Straight Street’ on Prodigal Son in 2018; it is no less relevant today than it was in the 1950s.

To turn from lies, to move away from the ‘liar’s house‘ is the beginning of conversion and draws on the image of the Apostle Paul’s conversion when he was living on Straight Street in Damascus (Acts 9:10-12).

When living beside the “liar’s house,” the songwriter says he had “very little guide of mouth.” It’s an interesting phrase, and not one I have heard before listening to this song, but images from James 3:1-10 might help make sense of it.

James 3:2-5 says:

Anyone who makes no mistakes in speaking is mature, able to keep the whole body in check with a bridle. If we put bits into the mouths of horses to make them obey us, we guide their whole bodies. Or look at ships: though they are so large and are driven by strong winds, yet they are guided by a very small rudder wherever the will of the pilot directs.

The twin images of bits and rudders indicates the need to guide the tongue and how we speak at all times to keep ourselves on the straight path.

But what is the ‘guide of mouth’ – the bit or the rudder, for us? What helps us keep the tongue in check and ourselves from telling lies?

James 3:9-10 says that with the tongue “we bless the Lord and Father, and with it we curse people, made in the likeness of God. From the same mouth comes a blessing and a curse. My brothers and sisters, this ought not to be so.”

James suggests that when we recognize that each person is made in the likeness of God, the God whom we bless with our prayers and who loves each person, we ought to have second thoughts about lying or otherwise harming people with our speech, and we ought to be careful always to speak truthfully and honestly.

In election seasons, whether in Canada, the USA – and anywhere else, and truly at any time – our speech needs to be shaped by love of God and love of neighbour.

In ‘Straight Street,’ the singer says that his “heart got troubled all about my dwelling place, I heard the Lord when He spoke to me, and he told me to leave that place. So I moved, I moved and I’m living on straight street now.”

John Martens

Since speech can be so fiery and our emotions so passionate about matters dear to us, whether political, social, cultural or personal, we might have to pack up our bags any number of times and move from the dwelling beside the liar’s house.

We might justify our lies by our righteous causes, our rationalizations might make us feel comfortable and at home, but we need always to be ready to pick up and move to Straight Street over and over.

And the song assures us that since the move to Straight Street, “I’ve got peace within. I thank the Lord for everything, so glad I found new friends.” I’ve made the move a lot of times and I can assure you, there’s always vacancy and we’re always welcome.

John W. Martens is a professor of theology and director of the Centre for Christian Engagement at St. Mark’s College at the University of British Columbia.

He has written this comment as a member of The Bell: Diverse Christian Voices in Vancouver. Go here to see earlier comments in the series.