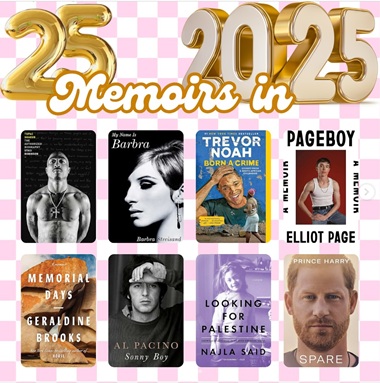

From the Instagram account of an American who wants to read 25 memoirs this year.

As we move through ‘June-uary,’ many Vancouverites are looking forward to heading out on vacation – to one of our many islands or simply to a local beach.

If you’re like me, one of the most important accessories on these summer excursions is a good book.

As I peruse best-seller lists and gather annual suggestions from friends and acquaintances for my summer reading list, I’ve noticed a significant uptick in one particular genre: autobiographies and memoirs.

Memoirs on the rise

Two things stand out to me about this genre. First is the increase in volume. Depending on which search terms are used (memoir, autobiography, biography) and which Western markets are considered (U.S., U.K., Canada), biographies have grown immensely in popularity throughout the 21st century.

But in the past 10 years, we’ve seen a further spike, with increases ranging between 26 percent and 34 percent. While the exact numbers vary, a quick trip to a bookstore or library will easily confirm the trend: memoirs are having a moment.

Second is the shift in the types of autobiographies available. There’s been an increase not only in the diversity of voices – particularly those from underrepresented or historically marginalized communities – but also in the age range of authors.

More memoirs are being written by people in their 20s to 40s, recounting a specific season or time in their lives, rather than the traditional life-spanning retrospectives written in later years.

This has led me to wonder: Why is there such a market for people telling their stories?

The crisis of narration

One possible answer comes from philosopher Byung-Chul Han. Building on the work of other thinkers, Han observes that in the past, our lives were embedded within larger cultural narratives – often with a spiritual or religious dimension – that placed individual stories within a cosmic frame.

These shared stories animated personal identity, secured our place in society and, borrowing a phrase from sociologist Peter Berger, provided a ‘sacred canopy’ that shielded us from existential uncertainty and meaninglessness.

In contrast, Han argues, the modern world has largely deconstructed or rejected these cultural meta-narratives. Whether because they were oppressive, incompatible with modern life or seen as limiting personal freedom, these big stories have lost their authority.

In some ways, this has been a positive shift – it’s allowed individuals to define themselves on their own terms and empowered societies like ours to name and confront colonial and harmful histories.

On the other hand, Han believes this narrative vacuum has led to what he calls “The Crisis of Narration” (also the title of his 2024 book). Without a shared story to locate our lives within, we are now pressured to craft our own narratives to find meaning and coherence.

Enter the modern hunger for memoirs. These are stories where someone has done the hard work of reflecting on, sorting through and narrating their experience in a way that gives it purpose and structure.

Michelle Obama expresses this beautifully in her 2018 bestseller Becoming:

There’s power in allowing yourself to be known and heard, in owning your unique story, in using your authentic voice. And there’s grace in being willing to know and hear others. This, for me, is how we become.

If telling our stories is how we ‘become,’ what do the stories we tell – and the ones we consume – reveal about us?

Three mystical pathways

In The Church in the Age of Secular Mysticism, author Andrew Root identifies three mystical pathways that shape the way people use storytelling to make sense of their lives.

- The mystical pathway of inner genius

This narrative centres on the self as the source of truth and meaning. It asserts that personal expression is the key to fulfillment, and emotional authenticity is a form of truth.

Examples include Glennon Doyle’s Untamed and the many biographies of Steve Jobs.

While Root acknowledges the empowering potential of this pathway, he warns of its fragility. It requires a high degree of privilege and autonomy and places the full weight of meaning and transcendence on a single life.

As Root puts it: “The inner genius must perform its own salvation. But when it cannot, there is no Other to meet it.”

- The mystical pathway of heroic action

This narrative turns outward, finding meaning not through inner truth but through self-sacrifice for a greater cause. It’s the story of becoming an agent of justice or change, often through adversity.

Examples include David Goggins’ Can’t Hurt Me and Tara Westover’s Educated.

While these stories are inspiring, Root cautions that this pathway can also be spiritually fragile. It risks burnout – either because the world’s brokenness is too vast or because the cost of sustained self-sacrifice becomes too great. Here, the individual becomes not their own saviour, but the saviour of the world.

Mixed narratives and churches

Many ‘inner genius’ storytellers blend in heroic action by labeling themselves as ‘activists’ or ‘changemakers.’ Especially in influencer culture, this signals moral seriousness – ‘I’m about more than just me’ – without giving up the centrality of self.

Root also notes that it’s not just individuals, but churches that adopt these mystical pathways.

A church centred on the ‘inner genius’ becomes irrelevant, as it offers nothing larger than the self. A church focused on ‘heroic action’ risks becoming just another NGO, where God is no longer encountered as a living presence but deployed as a motivational tool for good deeds.

- The mystical pathway of confession and repentance

This final pathway tells a different kind of story – one that emphasizes vulnerability, addiction, loss and moral failure. These memoirs often displace the self as the hero and instead focus on suffering and brokenness.

Examples include Chanel Miller’s Know My Name and Roxane Gay’s Hunger.

Root warns this storytelling can be driven by two very different forces. One is performative – a way to avoid cancellation and repair public image without true transformation. The other is authentic confession, seeking real forgiveness and healing.

Questions to take with you

- Where have churches failed to tell the meta-narrative of confession, repentance and forgiveness?

Have we offered forgiveness without deep, reflective confession? Or demanded confession without proclaiming joyful absolution? -

John Hau

As you pick up a book this summer or talk to friends about their summer reading, what mystical pathway is it inviting you down?

And just as importantly, how are you spinning your own story to make meaning?

John Hau is lead pastor at Reality Church and the COO of Colours + Shapes, a multidisciplinary creative studio, both in East Vancouver.

He has posted this comment on this site as a member of The Bell: Diverse Christian Voices in Vancouver. Go here to see earlier comments in the series.