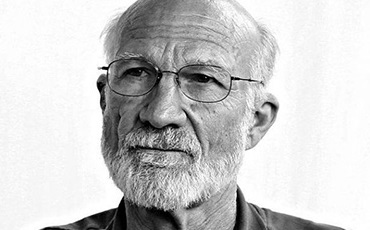

Stanley Hauerwas will deliver the Laing Lectures at Regent College March 20 – 22.

The annual Laing Lectures are coming up next week (March 20 – 22) at Regent College.

Derek Witten, senior writer and editor in Regent’s communications department, spent a few minutes on the phone with Dr. Stanley Hauerwas, getting a sneak peek into what he’s going to talk about, and why he thinks it’s vital.

In this interview, Hauerwas discusses the new christological humanism, how to recover our theological voice in the world and the crucial message that Karl Barth’s World War II writings offer in our current cultural climate.

Derek Witten: The topic of Christian or theological existence today has reappeared perennially in your work. What drew you to revisit this topic in the upcoming Laing Lectures?

Stanley Hauerwas: I thought it was a wonderful opportunity for me to try to show how Karl Barth did what I’ve tried to do so much better, early on, in World War II. And to show how Barth operated in such a wonderfully constructive way for helping Christians negotiate the world in which we find ourselves. I’ve been [using] the same ideas that Barth had – I obviously learned them from Barth – so I am trying to give in these lectures a background account of what has always been there.

DW: To what extent then would you draw the parallel between what we are facing now and what Barth was responding to? How do you draw insight for today out of his response to Nazism and communism?

SH: The issues are christological in how he is able to distinguish between what the Nazis did in establishing a counter church and what the communists did in not trying to establish a counter church but simply to take over the world. Barth didn’t think the attempt to take over the world was all that justified, but he thought that the very absence of religious convictions among the communists was an advance just to the extent that Christianity was not being confused with the world.

DW: How does this relate to today’s context? To what extent do you feel that [our culture] is attempting to build an alternate church and to what extent is it simply secular?

DW: How does this relate to today’s context? To what extent do you feel that [our culture] is attempting to build an alternate church and to what extent is it simply secular?

SH: I think the general description people would use is that it’s simply secular, but I think that’s a mistake. I think that what we see is a kind of glorification of what in general is called democracy as the true faith that Christians ought to support, even though the very institutional forms of democracy undercut any ability to say what we believe as Christians as true. I’m drawing on Barth to try to show the alternatives the cross makes for how you think of the church’s engagement in the world.

DW: You talk in these lectures about the importance of the recovery of the visible church. What do you mean by this?

SH: It’s been a common theological move to distinguish between the visible and the invisible church, associating the church faithful with the visible church. It must exist but we never see it. But I think that there’s a kind of docetic christology and ecclesiology associated with that move to excuse us for being less than what we’ve been called to be.

DW: Can you unpack “docetic?”

SH: Docetism is the christological heresy that failed to acknowledge Christ’s full humanity. So [emphasizing the visible church] is my way of trying to make us more serious about our identity as Christians as an alternative to the world. . . . We have to take the risk of Christians actually looking like Christians.

In some ways the payoff for all that comes in the third lecture in terms of the church’s engagement with civil society, where I draw on Barth’s way of drawing analogies from Christian practice and theology for giving us guidance about how the world’s politics is best understood.

DW: In your third lecture you also discuss Barth’s “new humanism.” Could you define that?

SH: Barth’s new humanism is christologically determined. He knew what he was doing when he said that. And that was counter to what people thought was a recovery of humanism after World War II. And Barth would have nothing of it.

DW: Can you expand on “christologically determined?”

SH: It means that Christ has made us more than we otherwise could imagine by calling us to be a follower. That turns out to be the most determinative formation we could have to be human. And part of what that entails is as Christians we’re not called to be more than human. We’re called to be human. And that’s a modest and realizable way of life.

DW: That sounds like your quote: “the first task of the church is not to make the world more just but to make the world more the world.”

SH: That’s right. One of the things I’m trying to do in these lectures is – when you take a kind of judgment like that – is to show its theological rationale by drawing on the work of Barth.

DW: You also focus on how to recover a strong theological voice in a “dying christendom.” How do we do this?

SH: Well I’m trying in these lectures to do it – to unapologetically show the centrality of God as Trinity for how we understand all of existence.

DW: Are there specific practices we can adopt to recover a strong theological voice?

SH: Yeah. Preach truthfully [laughs]. One of the bottom lines for me is the recovery of serious Christian vocabulary for the formations of sermons. I think it’s very important that Christians not let themselves be seduced by the vocabularies that have been discovered and reinforced by liberal political processes.

DW: What do you hope that each attendee will walk away from these lectures with?

SH: A sense of joy at watching theological work be done without apology. I’ve never been to Regent so I’m looking forward to it.

To go deeper, join Hauerwas next week (March 20 – 22) for the 2018 Laing Lectures at Regent College. This interview is re-posted by permission.