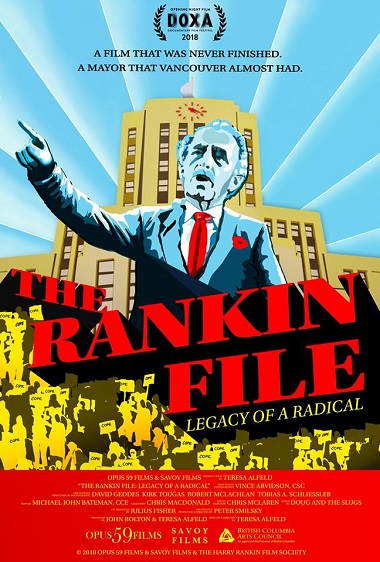

The Rankin File will be showing as part of the DOXA Documentary Film Festival. Image from the Facebook page.

Vancouver has changed dramatically over the past 50 years. Everyone knows that, but it is not until one looks at specific leaders or movements that the message really sinks in. A new documentary about a radical civic politician and a book about BC’s labour history illustrate that gulf perfectly.

The Rankin File

Christopher Cheung of The Tyee just posted an interesting interview with Teresa Alfeld, who recently completed a movie about Harry Rankin. The article began:

Harry Rankin was a Second World War veteran, criminal lawyer, Vancouver city councillor and socialist icon. He was described in a 2002 Globe and Mail obituary as “loud, profane, bombastic, ungracious and unforgettable.” If this larger-than-life legend and fighter for underdogs had succeeded in his campaign to become mayor of Vancouver in 1986, the city would have gone in a very different direction.

A long-awaited documentary chronicle of Rankin is finally complete. It began with that fateful 1986 campaign when Peter Smilsky, a lawyer-turned-documentarian, was shooting a film on Rankin. The project was never completed.

Fast forward to 2010. East Vancouver-born Teresa Alfeld, fresh out of film school, unearthed Smilsky’s reels in the basement of Harry Rankin’s son Phil, and completed the film with new interviews.

Directed by Alfeld, The Rankin File: Legacy of a Radical will premiere at DOXA in Vancouver on May 3.

Harry Rankin was the COPE candidate in the 1986 mayoral elections. Screenshot from The Rankin File.

As to whether Rankin might have changed the direction of Vancouver had he won the mayoralty race, I’m not sure that was ever in the cards. He was too radical for a small town looking to make its mark on the world; he lost the mayoral race to NPA candidate Gordon Campbell during the year that Expo 86 brought the world to Vancouver’s door.

Alfeld makes the case that things could have been different – maybe still could be different – during the interview:

Harry Rankin and Gordon Campbell presented very distinct and different views.

Harry wanted protections for renters and he wanted affordable housing. He wanted social housing in the proposed development on the Expo lands and to make them accessible to all people, not just those who could afford it.

Then there was the Gordon Campbell view, totally market-focused. In the film footage, Campbell said a lot about taking advantage of opportunity and of wanting to open B.C. and Vancouver up for business. It was a different paradigm than what Harry was working with. Understanding the difference between these paradigms is important today from my perspective as a millennial here hoping to continue to be able to live in the city.

Tom Hawthorn’s obituary in the Globe and Mail offered several insightful comments about Rankin which cast some light on why he did not prevail:

A Communist in all but party membership, Mr. Rankin was a utopian whose dream society proved to be a dystopian horror, a reality he firmly rejected. He would brook no criticism of anything Soviet. His political convictions were forged in the communist-fascist crucible of the 1930s.

Mr. Rankin was immune to the influences of the New Left of the 1960s and the identity politics of recent years. He thought the former were egghead dilettantes and the latter pandered to a patronizing, middle-class tokenism.

Of course, there was much more to Rankin than a brief analysis of his politics can reveal.

My experience with Harry

Harry Rankin was, surprisingly perhaps, appreciated in our comfortable West Point Grey home. He was first elected to Vancouver City Council in 1966, when I was just 14. My middle of the road parents voted for him faithfully because they trusted him to “keep things honest” and “speak up for the little guy.” That view was widely shared around the city, and helps to explain why he remained a staple in city politics for a quarter of a century despite his radical views.

Some 15 years later, I had a chance to meet Harry in person, as an articling student at his law firm. We didn’t spend a lot of time together, and though he was fair to me, my main memories are of his aversion to religion.

One of his first comments to me was, “What’s a bright young guy like you doing in a racket like that?” A racket like religion, that is.

Another time he railed against Mother Teresa, saying that if it weren’t for do-gooders like her ameliorating the miserable situation of the poor in India, the lumpenproletariat would have seen the light and joined the revolution. Something like that.

Friend of the poor

Harry Rankin wasn’t a fan of religious types, but he made some exceptions. Screenshot from The Rankin File.

But I also remember him working Saturday mornings – articling students in tow – offering free legal advice to people in the Downtown Eastside. (His office was at the foot of Main Street, near the criminal courts.)

And that’s when he acknowledged that he had some time (rather inconsistently, given his comments about Mother Teresa) for some of the Christians ministries working not far from his office. Among those he might have considered a ‘fellow traveller’ was May Gutteridge, who ran St. James Social Services for more than 30 years

Vancouver Sun writer Douglas Todd described her as “feisty” and a “devout Christian” when he wrote her obituary: May Gutteridge’s tough-talking legacy.

Ironically, Rankin and Gutteridge died on the same day, February 6, 2002. Todd wrote:

“They were friends – and combatants too,” [St. James Anglican Reverend David] Retter said, noting Gutteridge and Rankin recently met in hospital and enjoying talking about old times.

An official for Greater Vancouver Anglican diocese, Neale Adams, said Gutteridge and Rankin were both passionate defenders of the poor. But they sometimes locked horns because left-wing Rankin wanted to focus on erasing the causes of poverty and Gutteridge concentrated on taking care of the disadvantaged.

One of the comments made in response to Cheung’s article made a similar point:

On the Line

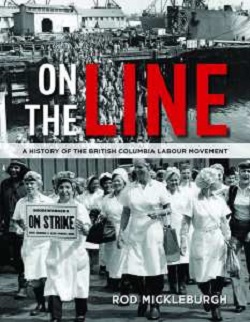

Harbour Publishing has just released an important book by Rod Mickleburgh, On the Line: A History of the British Columbia Labour Movement.

Harbour Publishing has just released an important book by Rod Mickleburgh, On the Line: A History of the British Columbia Labour Movement.

Rankin would have liked the book, which reminds us of bygone days, when BC was known around the world for the militancy and effectiveness of its labour movement.

Mickleburgh said the history of the labour movement in BC is a history of gains won, then eroded.

“The employers never stop trying to roll back conditions if they can.” Mickleburgh said.

“It’s always under attack.”

Many of the benefits workers enjoy, like eight-hour days, weekends, overtime pay, sick leave, unemployment insurance and the minimum wage were not the result of “benevolent employers,” but were won by workers in unions, Mickleburgh said.

“You just have to take your hat off to them,” he said.

Maybe things would have been better if Harry Rankin had won in 1986. As Cheung said, the documentary “may leave you longing for a Vancouver that never was, but could have been.” And maybe the labour movement can regain its strength. Time will tell.

In the meantime, The Rankin File and On the Line both offer important insights – which will remind some, and instruct others – about key elements of Vancouver’s history.

I thoroughly enjoyed the documentary, The Rankin File. As a lifetime BC resident born in Vancouver and raised in North Burnaby in the 1950s and 60s, I had heard of Mr. Rankin, but until I saw the film on the Knowledge Network, I knew little about him.

I have come to appreciate the work he did on behalf of the people of low incomes in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Sadly, it seems that since Harry retired? and died in 2002, not many gains have been made for people in that part of town.