Wayne and Esther Northey with Bishop John Rucyahana (beside Esther) and two of his associates.

Wayne Northey has devoted his life to practicing and studying reconciliation, peace-making and justice. He oversaw the work of M2/W2 Association – Restorative Christian Ministries until his retirement in 2014 and is still “a keen promoter of restorative justice.”

Wayne and his wife Esther spent almost two months (mid-May to mid-July) in Rwanda. What began with a plan to attend the International CURE Conference (the organization’s theme is ‘today’s inmates are tomorrow’s neighbours), expanded to include meetings with leaders of several reconciliation movements, participation in grassroots reconciliation activities and visits to communities devoted to personal and cultural peace-making.

Rwanda is best known in the west for the 1994 genocide which claimed as many as a million lives.

Northey has written four lengthy dispatches, which are well worth reading. What follows is a small portion of what he has written, hopefully enough to whet the appetite for more.

Colonial background

Colonization meant embracing a track of slavery’s first cousin: brutal subjugation and oppression of a people to maximize domination to extract maximum wealth. This was modus operandi the world over by Europeans and too often with Christian missionaries’ consent (and that of their converts): in direct contradiction of Jesus:

Jesus called them together and said, “You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their high officials exercise authority over them. 26 Not so with you. Instead, whoever wants to become great among you must be your servant, 27 and whoever wants to be first must be your slave – 28 just as the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many.” (Matthew 20: 25 – 28) . . .

Bishop John [Rucyahana] notes that under colonial rule, Rwandans were reduced to slavery or worse, through forced conscription, for instance to build roads – public works that were harshly enforced. He writes:

Like all colonial masters, the Belgians exploited African resources. There was very little regard for Africans as human beings. The colonizing nations believed the African brain did not function like their own brains, and saw them as second-class beings, somewhere between themselves and the animals in the jungle . . . It’s not a great loss to lose 10 thousand or even a million of these subhuman people to build the road. They have to serve the superior humans. (Rucyahana, John. The Bishop of Rwanda, Thomas Nelson. Kindle Edition, pp. 11 & 12, & 16).

In 1894 the first European, a German Count, set foot in Rwanda, and by 1897 it was a German colony – even if the Rwandan people did not know it at the time! One hundred years later, in 1994, genocide horror engulfed the nation. . . .

At the end of World War I, the newly-formed League of Nations assigned rule of Rwanda to Belgium. Deep racial bias based on completely specious “science” attributed the minority Tutsi with superior human traits, because, it was claimed, of their presupposed naturally superior Caucasian ancestry. This same “science” was introduced by the Nazis in 1931, and the horror of Holocaust began . . .

The Belgians issued identity cards to differentiate Tutsi from Hutus in 1933. Jump ahead to April 1994, and Tutsi identity cards had become death warrants, when in 100 days upwards of one million Tutsi were mercilessly and gruesomely slaughtered – at five times the rate the Nazis massacred the Jews.

Many church denominations had priests and pastors, nuns and lay persons and others, betraying their flocks and fellow congregants, luring them to their churches with promises of protection, aiding and abetting the killers, participating directly in the killings. Priests bulldozed their churches to crush to death the Tutsi who had fled there for safety. Nuns provided gasoline to burn churches and those sheltered inside.

Some said of this horror that “the blood of [false] ethnicity was thicker than the water of baptism.”

Reconciliation

Reconciliation grew out of the Rwandan horror, at once Christian-based, government-promoted, business-blessed, with aspects generically Rwandan. . . .

One can argue that post-genocide Rwanda took a page directly from the New Testament, in particular from Paul the Apostle in its approach to the profound need for the healing of Rwandans, of the nation of Rwanda.

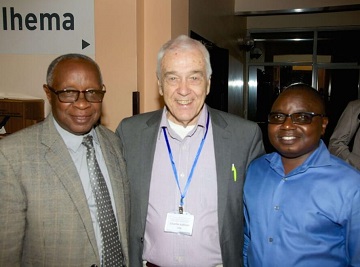

Bishop John Rucyahana (left) with Charlie Sullivan (founder with his wife of CURE) and Pius Nyakayiro of GNPDR.

And in fact, Bishop John Rucyahana was one of those who invariably referenced Jesus and Paul in his outstanding contributions to the work towards rebuilding/reuniting the people of Rwanda.

In 1995 Prison Fellowship Rwanda (PFR) began its post-genocide work. Its then and continuing board chair has been Bishop John. In 1999 the National Unity and Reconciliation Commission (NURC) was founded by the government to promote what the name indicates. . . .

We have heard repeatedly that modern-day Rwanda is a fragile work in progress. But we have heard repeatedly about Hope as well – one that the Apostle Paul says “does not disappoint” when anchored in Christ. “Hope” in Greek Tragedies was ever the Trickster like the North American indigenous Raven or Coyote. Just as there emerged Hope that all seemed to be turning towards the good, disaster would strike and Hope would be dashed. Not so says Paul is the Christian Hope! . . .

So in that Hope, captured in the biography of Bishop John by the title, Jesus: Hope of the Nations, Rwanda may continue to strive towards national resurrection. With no one left behind! Amen.

The conference

The schedule included plenary speakers and break-out groups, as well as visits to a Rwandan prison; to the genocide memorial in Kigali; to another memorial in Nyamata at a church where thousands who sought refuge had grenades, machetes and all manner of other instruments used against them until the killers were satisfied all were dead. . . .

This was all thanks in large part to the skills and tireless work in particular of Pius Nyakayiro and Good News of Peace and Development for Rwanda (GNPDR) [and others] . . .

The story of Pius

Pius in conversation with us more than once had alluded to his experiences during the genocide. He told us he would tell us his story in full at an opportune time. We knew in advance that we were never permitted to ask anyone for their story. The occasion to hear Pius’ story was Saturday, July 7 in his home, just days before our planned departure from Kigali. . . .

Pius Nyakayiro

With four other Tutsis, he boarded a bus for the Kigali airport. Half way there, in the town of Rwamagara, the bus driver, having heard of trouble in Kigali, refused to go further. Pius knew one woman in town through the church, who took them in for the night. They had hoped to continue on to Kigali the next day. Had they done so the day before, almost certainly they would have been murdered when the genocide began there on that day, April 7, 1994.

What made them remain in town was the news they had heard that morning that the President of Rwanda, together with the President of Burundi, and of course the crew – as the airplane came in to land – exploded in the air from two missiles launched from near the airport. Though that President had been a brutal dictator towards the Tutsis, even greater extremists in the government wanted him out of the way for the meticulously planned genocide to go ahead. There is little doubt the extremists fired the missiles, though the Tutsis were immediately blamed, justifying the commencement of the bloodletting. . . .

Pius and friends spent two weeks in the same house. One with them, a journalist connected to the Rwandan Patriotic Front, was convinced they would all die. They could hear gunshots around them, and the screams of those dragged from their houses and murdered.

Then, in the evening after two weeks, the deadly Interahamwe found them. They were the “Hitler Youth” of the genocide. They asked what they were doing there. No one answered. They told the occupants that they had to be killed. The woman with them said to her fellow house occupants it was up to God whether they would live or die. They were told to lie down; did so and expected the worst.

Pius suddenly remembered he had the money for his flight, and offered it to them. He also boldly told them not to defile themselves with their blood, and if they abstained, God would have mercy on them.

The soldiers took the money, told them they should really die, but said as they left that they would honour the agreement made in receiving the money. They returned however within minutes. Again all expected their deaths. Instead, to everyone’s shock, the soldiers asked them if they knew of a better hiding place! No one had any idea. Instead, the youth took them to a local pastor’s home, charged him with protecting and taking care of them, saying that he was to tell no one about their hiding place, and that they would return to be sure his charges were still alive. The soldiers never returned.

They were kept in a darkened room for two weeks with minimal food and water. They heard death all around them.

After that time, there were suddenly sounds of a military convoy travelling towards them. It was the RPF! The army, under the leadership of the current President, Paul Kagame, would eventually stop the genocide – without assistance from any outside source. They moved the group to a refugee camp behind their lines. Pius heard many stories there of mass murder. But he found out nothing of his family’s fate.

So before the country had been “stabilized” by the RPF, with many killers still on the loose, he took his chances and travelled back to his village. It was in utter ruins and a ghost town with bodies everywhere. He proceeded to a nearby refugee camp, and learned that there were only three survivors from his church family, and that many from the town had fled to Tanzania. He found out nothing about his own kin.

On his return one evening to a nearby refugee camp he had gone to, still in search of his family, he met one of the killers on the road. Pius was overpowered and dragged into the forest where he began to be beaten mercilessly with a large stick. The man said he was going to kill Pius. Pius prayed that God would receive his soul. The man suddenly stopped, and Pius heard a voice telling him to get up and run away. He was not pursued.

Though Pius was in a very weakened condition, he managed to crawl to a banana plantation to hide. He waited and listened through the night, bleeding and in very bad shape. He could hear hyenas and dogs in the distance. They had lost all fear of humans, feeding on the corpses. He wondered whether wild animals might find him. He prayed. He never knew the source of the voice. But there were yet to come encounters with his attacker.

Pius exerted the next morning what little strength he had left to make it to an RPF compound where he was immediately hospitalized. While spending a week there, he learned the fate of his family: 12 immediate members had been gruesomely murdered.

When he left the hospital, he found Rwanda in ruins physically, and in every other way imaginable. It matched his own tattered spirit. He like millions of others was angry at God, broken, devastated, hateful, bitter – including against himself. Life had become meaningless. He had lost the will to live. . . .

In the midst of all this, the man who had beaten him was captured. One day later on, soldiers brought him to Pius, asking what should they do with him? Would Pius forgive him? Pius had no answer. He knew however that in his heart there was no forgiveness. The Commander told the soldiers to each pick up a stick, and hit the attacker as hard as he would demonstrate, until he told them to stop. The Commander took one of the sticks from a soldier, and suddenly whacked the soldier hard! That “whack” modelled, the attacker was beaten in front of Pius to within an inch of his life. Pius remained mute and affectless.

In August 1994, Pius moved to Kigali to try to kick-start his life. The devastation was beyond imagining. Pius knew in his Christian faith that he needed to forgive, but still could not muster up forgiveness in his heart. Then one day the penny dropped, the dam waters broke, and Pius suddenly could find that latent forgiveness, exercise it, and be immediately freed of acrimony and bleakness of spirit. He took further spiritual and practical steps when he began finding new ministry legs in pursuing ways to contribute to rebuilding Rwanda.

In an Internet search, he came across an international American organization called Good News Jail and Prison Ministry. In 2006 he founded in consort with them Good News of Peace and Development for Rwanda (GNPDR). He had become a prison chaplain in 1996, and had gone on to become country director of chaplains for all Rwanda: a huge task. The international ministry remains supportive of the program in Rwanda. Pius continues to be a man of boundless energy, fully dedicated to his work.

In Kigali one day, Pius saw the man who had beaten him. Pius quickly ran after him, but the man, driven likely by fear of denunciation, ran away. Pius was not however chasing him to take the man to the authorities, rather to tell him that he had forgiven him, and why. Instead of that opportunity being taken however, Pius has since had occasion hundreds of times to tell génocidaires that he has forgiven them, and why; that God too can forgive them.

Wayne sat in on a sociotherapy circle.

This brings one to a mystery: Just what why motivates people to forgive? Just what why drives mass murderers to ask forgiveness?

Cynicism would preclude authenticity in the perpetrators, who simply may be hoping that a confession and asking forgiveness might be their “Get out of jail free” card. It has been so multiple thousands of times. And the cynics are doubtless right – some of the time! But by no means always. It is in this regard that I mention Survivors by Gregory R. Moffatt – who teaches psychology at a Christian university, and is nationally and internationally known. He indicates that in his writings he usually studiously avoids “religion.”

Moffatt avers:

But I’ve interviewed dozens of survivors and as much as it might be distasteful to those in the secular world, for most victims of trauma whom I’ve studied, religion was indispensable (p. 142).

He states that in particular, forgiveness is exceedingly difficult without a religious motivator. And he indicates that forgiveness is central to Christian faith. . . . But of course there are fine humanitarians in every religion and in none.

For Pius, comments Moffatt, he moved from a sense of Christian duty to forgive, to a deliberate choice to enact it. And once he began, he never looked back . . . And by continuing acts of forgiving, Moffatt observes – like the 70 times 7 in Jesus’ mandate (i.e. limitlessly) – Pius thereby released “the chains of memory that bound him to the past and the pain that resided there (p. 143).”

For Pius, comments Moffatt, he moved from a sense of Christian duty to forgive, to a deliberate choice to enact it. And once he began, he never looked back . . . And by continuing acts of forgiving, Moffatt observes – like the 70 times 7 in Jesus’ mandate (i.e. limitlessly) – Pius thereby released “the chains of memory that bound him to the past and the pain that resided there (p. 143).”

Moffatt cites psychiatrist Gordon Livingston:

Widely confused with forgetting or reconciliation, forgiveness is neither. It is not something we do for others; it is a gift to ourselves (p. 143, emphasis added).

This has been corroborated repeatedly by people who have been victimized, whom I have known or read about over the 45 years and counting of work in the criminal justice system.

Go here for the full story of Wayne and Esther Northey’s time in Rwanda. Wayne’s extensive dispatches cover much not discussed in this excerpt, including many moving insights into their personal interactions with Rwandans in a variety of settings. He discusses the uniquely Rwandan Gacaca court system, Sociotherapy Circles, Reconciliation Villages, the three main local ministries they worked with and much more.