St. Mark’s space will no longer be available to the Kitsilano community.

A couple of years ago, my family and I walked a few blocks to our church to take part in its annual Christmas lunch. The cross-section of people in attendance was remarkable: middle-class families from our church, older homeless men and people who were visiting Vancouver for the holidays and had nowhere else to go.

We ended up at a table with an exuberant man from Burnaby and his quiet, smiling adult daughter. As he glanced around the sanctuary, a plain, spacious room with windows that let in a lot of light and the surrounding greenery, he uttered a simple sentence that moved me unexpectedly: “I think this place is for everybody.”

I, too, believed this in some way, but I also knew, painfully, that it wasn’t true, and was soon going to be even less so, because the church was about to be sold to a developer for $12 million and will soon be – barring, well, an act of God – an apartment building, a space very few people in this city will be able to afford to occupy.

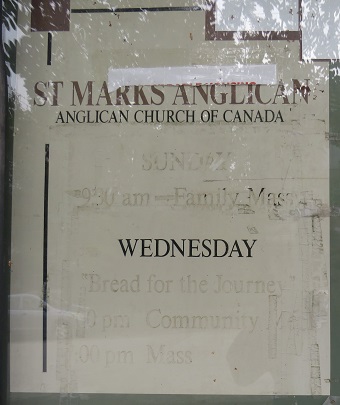

The congregation we belong to is part of a bigger church in Vancouver with several sites; the church has been renting St. Mark’s Anglican in Kitsilano for its services for the last few years. The building and the churches that meet in it have undergone no small amount of change in recent years. St Mark’s’ congregation moved out a few years ago, as they were too small to sustain a full-time priest; Trinity United Church, itself a merger of two United Church congregations, vacated the building earlier for similar reasons.

I don’t blame the Anglican Church, which I assume needs to consolidate its resources during a protracted period of change and conflict in its worldwide communion, for selling the building, nor am I surprised that neither our nor any other small local church or community organization was able to muster up the necessary funds to buy the building outright.

I know that we need more housing in Vancouver. I think it’s good that our neighbourhood is building new buildings. It’s a great place to live. You should come check it out.

What I do lament, though, is the communal space that is being lost. This “place for everyone” will no longer be one, even though some of the new units will, thankfully, be set aside for people with “moderate” incomes.

What I do lament, though, is the communal space that is being lost. This “place for everyone” will no longer be one, even though some of the new units will, thankfully, be set aside for people with “moderate” incomes.

The developer’s application for rezoning refers to St. Mark’s as a “disused ecclesiastical building” with “no tenants to re-home.” Well, maybe.

No one lives in the building, but as it has inched closer to being demolished, many people have been displaced. The Anglican and United congregations have moved. A preschool has closed. Meditation and addiction recovery groups have had to relocate or disband. A Scout troop that had been meeting at the church for nearly a century has had to leave. Folk concerts and poetry readings no longer happen here. People without homes who used to shelter in the parking lot rarely come around anymore. The sessions run by public health nurses for parents of newborns no longer meet. The Christmas lunch is a thing of the past, and our own church of 200 or more left last month.

We’ll be fine, of course; we found another place to worship, just as the others did. Some people think that religion simply is and has been on the way out for a long time, and maybe they’re right – only something like 30 percent of people in BC go to church regularly anyway.

But you don’t have to be a person of faith to see that when we lose a building like St. Mark’s, we’re losing a space where people in our community can be together. That open, spacious sanctuary where people mix and mingle, where we come together from out of our usually solitary single or coupled or parents-and-kids-family-unit lives, will become tiny boxes, subdivided silos, walls between neighbours.

Calling St. Mark’s an “ecclesiastical” building sounds technical and esoteric, until you remember that the Greek work “ekklesia” means “assembly.” I think of that hodgepodge of people at the Christmas lunch, looking for a place to be together, and finding welcome; a gathering of people from different backgrounds, places, life circumstances – and I can only lament that that place of assembly and welcome will soon be destroyed.

Sometimes at our church we sing a song with the lyrics, “I will build my life upon your love / It is a firm foundation.” When we were still at St. Mark’s, this song put me in mind of building and tearing down, and I’d look up at the ceiling, out the windows, to the trees and the light streaming in. I’d think of all the communal life that must have happened in this building over the decades – the weddings, the baptisms, the funerals, the love, the pain, the growth, a thousand other tiny intangible human things that mattered.

A Metric Architecture rendering of the proposed rental development at 1805 Larch Street in Kitsilano.

I hope and pray that the people who move into the apartments that replace St. Mark’s will continue to find ways to come together – that all of us in this neighbourhood will find ways to move beyond the social isolation that seems to be chipping away at our sense of community.

We can do this in the cafes and pubs and parks of our neighbourhood, sure. But there’s one place – a beautiful, open, spacious sanctuary, a place for everyone – where we won’t be able to do that any more.

Joel Heng Hartse is a lecturer in the faculty of education at Simon Fraser University. This comment first appeared in The Vancouver Sun and is re-posted by permission of the author.

A Georgia Straight article describes the development that will go up in place of the church building: ‘Vancouver rental with $4,000 monthly charge for three-bedroom unit qualifies as affordable housing.’

Sad. A stark reminder that community and place are inseparable.