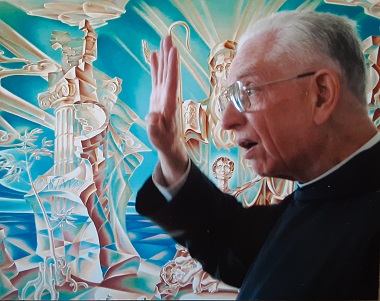

Fr. Dunstan Massey spent his adult life creating art at Westminster Abbey in Mission. Photo: Bev Wilson

When, on the day after Christmas, 2022, Fr. Dunstan Massey died in the infirmary of the Benedictine monastery in Mission, the church and the world lost one of its greatest Christian artists.

His death was no surprise: he was 98 years old. But it is no less a loss. (And those of us who knew him wonder whether his waiting to die till the day after Christmas was not a last deliberate honouring of the church he loved and celebrated through all his work!).

It will require the passage of time – and perhaps a substantial cultural revolution – for his greatness to be widely recognized. But no one who has seen the work he produced in his 70 years as a monk can doubt his stature.

His gifts emerged early. At the age of 16 he had a one-man show at the Vancouver Art Gallery. His potential was recognized at a very early age by other artists. While still a teenager he studied with Vancouver modernist Jack Shadbolt, was tutored by Lawren Harris, and was invited by another member of the Group of Seven, Arthur Lismer, to study with him in Toronto.

The interior of Westminster Abbey, which was completed in 1980. Photo: Bev Wilson

Dunstan appreciated the encouragement of these well-known artists, but he was influenced neither by their style, nor their invitation into fame.

At the age of 18, Fr. Dunstan, (who then was William, ‘Bill’ Massey), influenced by readings on medieval monasticism, and by Bernard of Clairvaux’s On the Love of God, decided to become a priest and a monk.

His teachers and supporters were generally shocked, feeling he was throwing his life away. But he was never in doubt about his calling. Also, he knew from his reading that the monastic life could nourish art.

He did tell his first abbot that he was willing to give up his art. But the abbot, recognizing what a gift the young monk could be to the new monastery – about to move from Burnaby to its hilltop site in Mission – reminded Dunstan of his vow of obedience: ”You’ll do what you’re told.”

And for the rest of his life, encouraged by three successive abbots, Dunstan has had the task and the privilege of turning the monastery into a visual meditation, through colour and molded concrete, of the life of Jesus and his followers down through history.

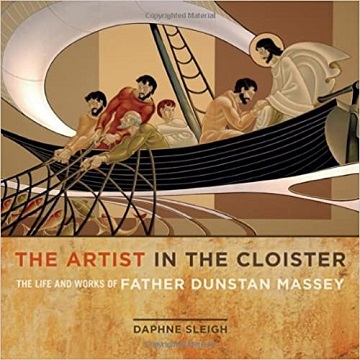

Short of visiting Westminster Abbey, the monastery in Mission, the best way to experience the work of this priest and artist is through Daphne Sleigh’s beautiful book, The Artist in the Cloister: The Life and Works of Father Dunstan Massey (Heritage House Publishing, 2012).

Short of visiting Westminster Abbey, the monastery in Mission, the best way to experience the work of this priest and artist is through Daphne Sleigh’s beautiful book, The Artist in the Cloister: The Life and Works of Father Dunstan Massey (Heritage House Publishing, 2012).

The two huge frescoes which are among his greatest works are in the cloister and cannot normally be viewed by the public. But his other great work is the array of life-sized-bas relief concrete sculptures in the Abbey church. And they are very accessible.

The church itself, the masterwork of Norwegian architect Asbørn Gathe, was finished in 1980, and is itself a great work of art, built for the daily prayers which are the heart of Benedictine life. (The public is welcome to take part, and the experience is well-worth the trip up the valley!)

But its soaring concrete pillars, though warmed by coloured glass, have a kind of austerity. As Fr. Dunstan once told a group of us, “Abbot Eugene said to me, ‘It needs to be humanized – that’s your job.”

This sculpture portrays a dream of St. Benedict; it is in the Chapter House, where the monks have meetings. Photo: Bev Wilson

Christians believe that they pray in and with the communion of saints, and over the next dozen years Dunstan evoked the presence of that communion through the creation of 20 full-sized bas-relief sculptures for the pillars.

They range from the angels Michael and Gabriel, through biblical figures like Moses and Peter, to men and women through the history of the church, into the 20th century – including the Jesuit missionary to Canada Jean Brébeuf (who wrote the Huron Carol).

Fr. Dunstan had to develop his own techniques and tools: first a clay form, then a plaster mold, then the final concrete, cast on a movable platform built to manipulate the heavy figures.

Fr. Dunstan was in the early stages of this project when Mary Ruth and I first met him. Another artist, Dal Schindell at Regent College, had put us in touch, and we visited him in his studio, downhill from the church, across a pasture, beside the barns. The lean, black-robed figure greeted us warmly, like the friends we were to become.

He was smoothing the clay on the muscled arm of Peter hauling up a net. The figures in all the sculptures, are vigorous and lively, even in repose – like Dunstan himself. (One student later said that “he has a sparkle!”)

Our purpose in that first visit was to ask if I could bring the students of a Regent class, ‘The Christian Imagination,’ to meet with him at the Abbey. He was enthusiastic about the idea. So over the next 30 years he was a gracious host to hundreds of students in many classes.

Monks daily walk down a hall in the cloister towards this fresco of the ‘Temptation of St. Benedict’ (founder of the Benedictine order). Photo: Bev Wilson

He always went out of his way to welcome us, often interceding with the abbot to let us visit works in parts of the monastery not usually open to the public.

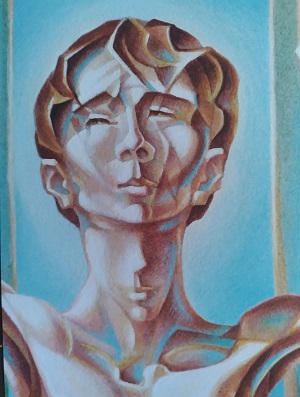

The mature Benedict, from ‘The Temptation of St. Benedict.’ Photo: Bev Wilson

The most memorable of these works – and the one for which he is most widely-known – is a huge (10’ x 15’) fresco of the temptation of St. Benedict, the founder of the Benedictine order. In brilliant blues and browns, it beckons at the end of a long hall down which the monks walk several times daily from their residence to the church.

As Fr. Dunstan once told me: “I wanted to give us the sense of walking back in time towards our founder.”

From a distance the large bearded figure of the grown man beckons, arms upraised in invitation and blessing.

But as one draws closer a story appears: within the larger figure is the double figure of a youthful Benedict, both casting himself into thorns, to avoid the temptations of a corrupt Roman culture – and with arms uplifted in triumph – holding a wafer of the eucharist.

The image is both timeless and modern, suggesting influences from both Picasso and Dali.

That was Fr. Dunstan’s first fresco. He always intended another, but it was interrupted for many years, mainly by the 12-year task of creating the sculptures for the church, each of which took about six months.

The youthful Benedict, from ‘The Temptation of St. Benedict.’ Photo: Bev Wilson

The technique of fresco painting – which requires the bonding of mineral colours to freshly-applied plaster to make an image with the durability of stone – was almost forgotten, and to do these works he had to recover the art of fresco, and learn to prepare the materials, a laborious task which took him years.

On the regular visits of our class to his studio he would point out shelves of colours in jars, along with barrels of slaked lime and graded sand. “That’s for the next fresco,” he would say – “a ‘Last Supper’ for the refectory” (the monks’ dining hall).

There were many delays, including a successful fight with serious cancer (the only year my class didn’t visit). “They said I was at death’s door,” he said with a grin on our next visit, “but I’m back at work now”.

Finally, at the beginning of the new millennium, as the artist was nearing 80, work on the huge fresco could begin – first with years of preparation of the wall. Over 30 feet wide, and nearly as tall at its arched high point, it dwarfed the large St. Benedict fresco. The work took several years.

It is called ‘The Celestial Banquet,’ and though it clearly alludes to da Vinci’s ‘Last Supper’ painting, it is not of the last supper, but the promised feast in heaven in which Jesus promises to once more drink wine with his friends.

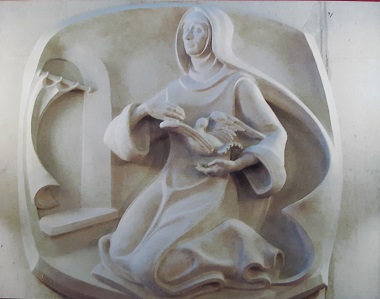

Benedict’s sister, Saint Scholastica, pictured at the moment of her death. Her soul is flying off in the form of a dove; legend has it that Benedict saw it fly past his monastery. Photo: Bev Wilson

As the glorious colours slowly covered the wall above the tables where the monks ate, they occasionally teased him (Daphne Sleigh relates): “Michelangelo did the whole Sistine chapel ceiling in four years, but you’re taking longer”.

The comparison with Michelangelo is not trivial. During the five-year process of the painting a Knowledge Network TV film was done about it, called ‘In the Footsteps of Michelangelo.”

On my class’s successive yearly visits we watched the fresco develop — first as a life-sized paper ‘cartoon’ in his studio, then on the refectory wall itself.

On one memorable visit we were permitted to spend the afternoon in the refectory, watching Dunstan, a small figure high on the scaffold, put the colours of a disciple’s face on the wet plaster left by his assistant. To the occasional whispers of appreciation from the students he looked down once and said, “I don’t see what you’re so excited about – I’m just painting.”

Regent College students admire Fr. Dunstan’s partially-completed second fresco, in the refectory. Photo Bev Wilson

That playful humour was typical of the man. Once, on another visit, Dunstan showed us another sculpture he was working on for the church – not in bas-relief this time, but fully in the round. It was of two angels, arms arched over a 16th century wooden sculpture of the Virgin Mary.

The angels were cast in concrete, like the walls of the church, and his purpose, he said, was to give that older statue a welcome into the modern structure. The clay form was almost finished, carefully wrapped in plastic.

Though we urged him not to go to the trouble, he wanted to show the angels to us. As he unwrapped one of the delicate hands, one of the clay fingers broke off. We were distressed at the damage. “Don’t worry,” he said with that sparkling grin. He gave the finger a quick kiss – and deftly reattached it to the wet clay!

What people remember most about Dunstan Massey was his irrepressible vitality. He seemed to be more alive than most people: excited about his work, eager to share it, and genuinely interested in the art of others.

Fr. Dunstan and Loren Wilkinson. Photo: Bev Wilson

And he was always planning his next project. The last one he shared with the class was a gold crucifix suspended above the altar.

He explained with delight how he had designed the figure, on its open-framed cross, to be visible from all sides – and how it could be seen not only as a Crucifixion, but an Ascension.

Fr. Dunstan was deeply rooted in his Catholic faith. What came across strongly to the students, and to myself, was the joy with which he lived out, through the life of prayer, the liturgical cycles, and the art of the church, the same Christian faith which we, as Protestants, shared.

There was never a hint of proselytizing, only a delight in speaking to people who shared his faith. But all of us – certainly myself – found our appreciation of the Roman Catholic tradition, and of monasticism, deepened. “If this is what a monk is like,” some would say, “maybe I’d like to be a monk” (or a nun).

In his mid-90s, many years after the other bas-reliefs for the Abbey church, Dunstan completed his last two sculptures (I remember his speaking hopefully about being able to do them before he died ). One was of the taking of Jesus’s body from the cross.

Fr. Dunstan always looked toward the resurrection. Photo: Bev Wilson

The other, his last full work, was of the resurrected Christ. In the last conversation we had with him he complained that his hand was not as steady as it used to be, and he needed the hand of a younger monk to steady it while he shaped the clay.

In a sense, all of Father Dunstan’s work, though stark in its portrayal of pain and suffering, looked towards the resurrection. This was particularly true of a major project in which I was privileged to have a small part.

He had written an epic poem on the Last Resurrection – accompanied by 157 pen and ink drawings. It was part of a long project of a film on the resurrection of the dead – which never came to completion. Fr. Dunstan began to share the work with our visiting class – laying the pages out, set by set on a long table for us to see, and reading key passages.

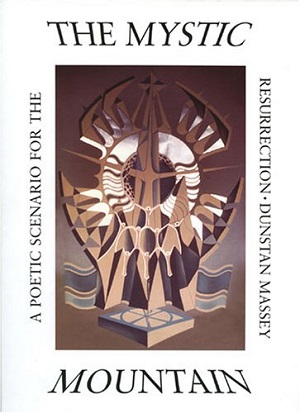

I put him in touch with Piquant Press in England, which was committed to publishing high quality works that brought together Christian faith and art. It was a perfect fit, and the book, The Mystic Mountain: A Poetic Scenario for the Resurrection, was published jointly by Piquant and Regent Press.

I put him in touch with Piquant Press in England, which was committed to publishing high quality works that brought together Christian faith and art. It was a perfect fit, and the book, The Mystic Mountain: A Poetic Scenario for the Resurrection, was published jointly by Piquant and Regent Press.

It is still available at Regent Bookstore, and is a beautiful journey, both in word an image, with a man seeking his dead wife and son, but never finding them. Finally there is a cataclysm; the man dies, along with all of humanity, and death reigns. But then comes the resurrection. The skeletons are re-fleshed (with imagery I will never forget).

The family is reunited, and follows the three voices, which have accompanied the whole quest, up a vast mountain – a mountain which takes the form of a Man, whose words echo now in my mind as I imagine how Dunstan might have heard similar words at last, on the day after Christmas, spoken to him by the Incarnate ‘second voice’:

O come unto me, burdened

my labourers, so heavily with sheaves,

and I will refresh thee; I have

trod the wine press too, with

blood my vesture, stained;

for I am the vintner, the harvester,

and the gardener too –

I am the Sower and the seed;

So come as I call thee

my sister, and brother,

and mother, unto me.

And surely Father Dunstan also heard, and continues to hear, “Well done, faithful servant.”

Loren Wilkinson is expecting his new book, Circles and the Cross: Cosmos, Consciousness, Christ and the Human Place in Creation, to come out later this year. His earlier books include Earthkeeping: Christian Stewardship of Natural Resources and Caring for Creation in Your Own Backyard (co-authored with Mary-Ruth Wilkinson).

He joined the Regent College faculty in 1981 and was appointed Professor Emeritus there in 2016. His teaching interests include Christianity and the arts, philosophy and earthkeeping. He has written many scholarly and popular articles developing a Christian environmental ethic and exploring the human relationship to the natural world in its environmental, aesthetic, scientific and religious dimensions.

Thank you for the sad news and wonderful information.

Wow! – said into the august silence of this beautiful life sketch. Thank you, Loren. Thank you.

You invited the reader onto holy ground.

When it was possible to have a retreat, late ‘70s, staying in a guest room on one’s own and having a silent meal with the brothers, I took part with small a group from Trinity Western. We were able to walk the halls to see all of the art. This was when the the chapel was still under construction. It was an amazing privilege as not all these places are accessible today.

Thanks Loren for making us aware of the depth of Fr. Dunstan’s work, and honouring his devoted life.

Dal felt such deep warmth, respect, and admiration, for Father Dunstan. May they both rest in peace, glorifying, worshiping, and enjoying God forever.

Beautiful article for a beautiful man, thanks Loren.

A most generous, informative and insightful overview of the life and artistic genius of Father Dunstan, Group of Seven taken to a deeper and more centred level, Christian art at its evocative and compelling best. I have lingered many an hour, when at the monastery, on the vocational vision of Father Dunstan – well done thou good and faithful servant.

Ron Dart