Woman’s Missionary Society worker with a group of Japanese Canadian women, about 1915.

Vancouver Japanese United Church fonds, BCCA 2804.41

The United Church Archives has found a home which suits its purpose well.

Regional Archivist Blair Galston clearly appreciates the environment; 312 Main (the address and the building’s location) has been transformed from the headquarters of the Vancouver Police Department – complete with city jail – into “a community-centred hub that fosters collaboration and innovation among organizations, artists and entrepreneurs.”

Galston particularly warms to the centre’s focus on reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples in the neighbourhood. He says the archive is working hard to reflect early church connections with local First Nations.

Asian Heritage

He is also keen to alert the Christian community, and beyond, to the important interactions with the Chinese Canadian and Japanese Canadian communities.

To coincide with Asian Heritage Month, the archives sent out an invitation May 1 “to explore our holdings relating to Chinese Canadian and Japanese Canadian communities in British Columbia,” saying:

The collections show the church’s relations with Chinese Canadians and Japanese Canadians that predate the formation of the United Church, beginning with Methodist Church outreach to Chinese Canadians in the 1880s. They include over a thousand photographs, some published histories and several registers from what was known as the Oriental Home and School in Victoria.

The digital collections have been published online in response to requests from people of Chinese and Japanese descent who are looking into their family history: “Our collaborative work with the Chinese Canadian Museum and Vancouver’s Chinatown Storytelling Centre has made the need all the more obvious.”

Complex legacy

Kindergarten graduates at Chinese Methodist Mission in Vancouver, possibly 1924. BCCA 2810.3

Some of the records are from the decades before 1900. The archive introduction states:

Missionaries who created many of these records acted in the context of their colonial society, which was racially segregated and shaped by anti-Asian sentiment. Their activities in many cases contributed to loss of heritage, culture and language.

This harmful legacy exists as part of a complex web of relations between Asian Canadians and the United Church, including nuanced experiences of community, both positive and negative.

The church provided social services and supports with a goal of helping Asian people assimilate into a White, Christian Canadian society. These services most sought to assist children, women and people newly arrived in Canada.

The early work of White missionaries laid a foundation for Chinese Canadians to engage in their own organizing, creating vibrant community spaces and enduring relations with the church.

Japanese Canadian Christians also received support in early years from the Methodist Church as missionaries in their community as they established and grew their congregations into self-supporting ones.

Mr. and Mrs. Ernest Lee’s family in the early 1900s; Oriental Home and School fonds. BCCA 2801.0032

Writing two years ago, genealogist Linda Yip wrote about the archives; here is a portion:

I looked at the Vancouver ‘Oriental Home and School fonds’ which begin in 1886 (the same year the city was incorporated). The home initially sheltered Chinese and Japanese sex workers and later women escaping abusive relationships.

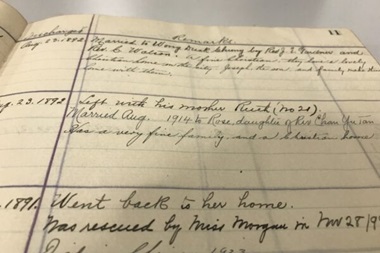

The registers are a collection of handwritten volumes, like a diary of the workings of the Oriental Home from the perspective of the staff. The registers cover every aspect, from the monies spent to the people ministered. One striking aspect of these fonds is the insight into the lives of the Chinese and Japanese women who lived at the home.

Go here for a record of the digital collections. Textual records include ‘Narratives of descendants of the Oriental Home and School’ and ‘A Hundred Years of Chinese Work in British Columbia, 1859 – 1959.’ Photographs include ‘Chinese United Church (Vancouver, BC) photographs, 1906 – 1993)’ and ‘Yoshinosuke Yoshioka fonds.’

About the Archives

Sample page from a register of the Oriental Home and School.

The archives hold records of the founding denominations of the United Church of Canada (Methodists, Presbyterians, Congregationalists), the Indigenous Church and the Pacific Mountain Regional Council (formerly BC Conference) of the United Church of Canada:

Holdings date from 1859 to present (1895 – 2010 predominant). It includes records created by local communities of faith such as registers of baptisms, marriages and burials; historic membership rolls and communion rolls; minutes of church boards, committees and organizations (including women’s groups); printed annual reports of local congregations; congregational newsletters; local church histories; correspondence; and photographs.

The official name for the United Church Archives is the ‘Pacific Mountain Regional Council Archives,’ but it is also known as the ‘Bob Stewart Archives.’ He began with the archives in 1981 and died in 2005.

(I remember meeting Bob Stewart working away on the archives at the Vancouver School of Theology – its original home – in the early 1980s, while I was at law school across the street and again, I think, while I was volunteering at the World Council of Churches Assembly at UBC in 1983.)

Get in touch

United Church Archivist Blair Galston in the storage area.

The archives are open to the public. Blair Galston would be happy to hear from anyone interested in the the history of the United Church locally, and of related groups.

“We want to be as warm and welcoming as we can be,” he says, but notes that appointments are necessary. Go here for contact information.

There are two main rooms, one for reading and one for storage, in the 1,800 square foot space. The third floor had to be specially reinforced to hold the compact mobile shelving units.

Linda Yip, in her very helpful introduction to the archives, even offered specific guidance about parking, how to get into the building and where to go for lunch.

I posted ‘Archiving the lives of displaced and interned Japanese Canadians’ in 2019 and followed up on it briefly a year later.