Imagine Van Gogh photo

Vincent van Gogh could never have imagined the art extravaganza now making its way from city to city.

Imagine Van Gogh: The Immersive Exhibition, “after a tremendous success in Paris,” has travelled across North America, setting up shop at the Vancouver Convention Centre last month (until August).

The organizers say of the exhibition:

The very concept of Imagine Van Gogh is grandiose: visitors wander amongst giant projections of the artist’s painting, swept away by every brush stroke, detail, painting medium and colour. Immersed in an extraordinary experience where all senses become fully awakened, viewers will be truly moved by such spectacular beauty.

Visitors discover more than 200 of Van Gogh’s paintings, including his most famous works, painted between 1888 and 1890 in Provence, Arles and Auvers-sur-Oise.

The art is beautiful, the presentation looks impressive, and I have no doubt that a visit to the exhibit would be worthwhile. But does the word ‘grandiose’ not leave an odd taste in one’s mouth?

Dorothy Woodend seems to have wondered something along those lines. Writing on The Tyee site, she asked, ‘When Van Gogh goes huge, what do we miss?’:

Maybe it’s just that, looking at the huge swathes of colour, brush strokes blown up to such an extent, they lose all scale and become abstracted versions of themselves. I wondered how something that started out in a such a humble fashion – a man painting a picture of some flowers – ended up as a multimillion-dollar industry, with three different competing shows [now touring the world] all vying to offer audiences an overwhelming experience.

Or maybe it’s the magnification of the idea of the mad genius artist. The big story sucks away at the smaller, less dramatic details. It’s always a shock to come face to face with his actual work in places like the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. The sketches, paintings and studies are far smaller than one might expect, given the artist’s outsized reputation. But nonetheless, their very humbleness is what gives them a certain presence. They don’t pretend to be anything other than what they are – an artist’s attempt to capture what he sees.

Go here for the full comment, which has some beautiful accompanying photos.

Sustained spiritual passion

Imagine Van Gogh photo

Writing about an exhibit of Van Gogh’s in Los Angeles more than 20 years ago, Los Angeles Times religion writer Teresa Watanabe wondered whether his spiritual depth would be appreciated.

She said:

As a young man, Van Gogh burned with religious fervor and won his first appointment to preach to poor coal miners in the Belgian town of Borinage in January 1879.

In what many secular biographies have termed his era of “religious fanaticism,” Van Gogh determinedly sought a life of acute asceticism. The goal, he told one acquaintance, was to be “a friend of the poor like Jesus was.”

He gave away his money and clothes, refused the lodgings of a miner family and slept crouched in the hearth of a bare hovel. He even refused the luxury of soap; his contemporaries recalled a shirtless, soot-faced, emaciated Van Gogh tending his flock with an intense ardor, Erickson’s book recounts. [Kathleen Powers Erickson: At Eternity’s Gate: The Spiritual Vision of Vincent van Gogh]

Despite his fervor and popularity with miners, the ecumenical Protestant organization that gave him the six-month appointment declined to renew it, citing Van Gogh’s lack of eloquence in the pulpit.

The crushed Van Gogh was further devastated when his own father withdrew support for his pastoral ambitions and, disturbed by what he viewed as his son’s excesses, sought to commit him to an insane asylum. In addition, his beloved Uncle Stricker, another staunch religious influence, rejected Van Gogh’s repeated attempts to woo his daughter, Kee.

The triple betrayal permanently alienated Van Gogh from institutional religion; he never set foot in a church again and took pains to express his bitterness in such works as “Starry Night,” where all village buildings glow with yellow light except the dark steepled church, Erickson said.

At this point, most biographers claim Van Gogh abandoned religion, but a new generation of scholars now say he retained his spiritual passion and only rechanneled it into art. He subscribed to French playwright Victor Hugo’s maxim, “Religions pass, but God remains,” scholars say.

The Imagine Van Gogh exhibition does offer a brief biography but doesn’t seem to challenge the traditional view, though, to be fair, it does recognize the “physical and spiritual vitality” of his late work.

Van Gogh’s words

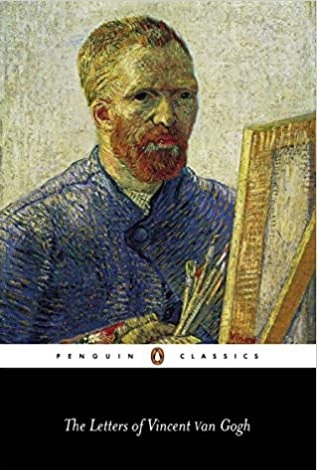

Having come across The Letters of Vincent van Gogh on my bookshelf recently, I found nothing that suggested a fondness for grandiose design.

Having come across The Letters of Vincent van Gogh on my bookshelf recently, I found nothing that suggested a fondness for grandiose design.

Ronald de Leeuw, in the Introduction, said:

Familiarity with the Vincent of the letters leads irrevocably to sympathy for, if not identification with, this struggling seeker after God, for this toiling artist who set himself such high ethical standards.

Following is a passage he wrote to his friend Emile Bernard from the south of France less than a year before he died. He had been suffering from epilepsy and had been confined to a mental hospital for a time:

Another canvas shows a rising sun above a field of young wheat – receding lines, furrows that run to the top of the canvas, towards a wall and a row of lilac hills. The field is purple and yellow-green. The white sun is surrounded by a large yellow halo. Here, in contrast to the first canvas, I have tried to express calmness, great peace.

I am telling you about these canvases, and about the first one in particular, to remind you that one can express anguish without making direct reference to the actual Gethsemane, and that there is no need to portray figures from the Sermon on the Mount in order to express a comforting and gentle motif.

The letters of Van Gogh are full of religious references, and would be a helpful companion for anyone planning to take in Imagine Van Gogh.

Consuming Van Gogh

Another book which could provide perspective on the exhibition – and on the church in materialist North America – is Skye Jethani’s The Divine Commodity. Zondervan, the publisher, stated:

Through Scripture, history, engaging narrative, and the inspiring art of Vincent van Gogh, The Divine Commodity explores spiritual practices that liberate our imaginations to live as Christ’s people in a consumer culture opposed to the values of his kingdom.

Each chapter shows how our formation as consumers has distorted an element of our faith. For example, the way churches have become corporations and how branding makes us more focused on image than reality. It then energizes an alternative vision for those seeking a more meaningful faith. Before we can hope to live differently, we must have our minds released from consumerism’s grip and captivated once again by Christ

Jethani may be overstating his case a bit, but his choice of Van Gogh as a guide does give one pause about the way in which his work is being promoted 140 years after his death. At least, prospective visitors to Imagine Van Gogh might want to be prepared for the onslaught of colour and music in “the zones, angles and sizes of the projected images.”

Having written all of this, I acknowledge that I am far from being an expert on art and would welcome any clarification or correction from those who are – especially from anyone who has actually immersed themselves in Imagine Van Gogh.

This is fascinating! Curious to know if any of the proceeds of these ‘grandiose’ exhibits are going to aid mental illness?