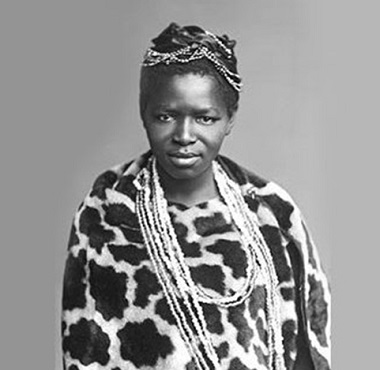

Charlotte Maxeke, ‘the mother of Black Freedom in South Africa – and a missionary in her own homeland – was a choir member with the African Native Choir.

Vancouver will get a glimpse into the long-neglected history of the African Native Choir this week – and even a cursory glance at the main players reveals a legacy which is still remembered with respect in post-Apartheid South Africa.

DanceHouse and Vancouver New Music present the Canadian premiere of Broken Chord through music, dance and narrative at the Vancouver Playhouse Thursday to Saturday (February 23 – 25).

Dance House describes the show:

From 1891 – 1893 a group of young African singers travelled by boat to Britain, Canada and America. This ensemble of missionary-educated Black people, named The African Native Choir, were on a mission to raise funds for a technical school in Kimberley, South Africa.

Inspired by photography from that tour and using traditional Xhosa and contemporary dance styles alongside atmospheric soundscapes, choreographer and performer Gregory Maqoma and musical director Thuthuka Sibisi weave together recorded personal accounts of the African Choir, revealing a drama of global dimensions.

Choreographer/dancer Gregory Maqoma, four singers from South Africa, and 16 members of Vancouver Chamber Choir tell the story of the African Native Choir’s visit to the West. Photo: Lolo Vasco

Choosing themes

It will be interesting to see to what extent the very strong Christian elements which motivated the African National Choir – and the national leaders it produced – will be present in the production.

While the original tour focused mainly on hymns, both English and African, DanceHouse doesn’t appear to highlight them:

With a single dancer (Maqoma), four vocal soloists and an onstage a cappella chorus, Broken Chord not only reflects on an archive but triggers, critiques and comments on urgent issues of migration, dispossession, borders and paths of forced closure, raising important questions about the relationship between the colonized and the colonizer, and either’s complicity in shaping and shifting a South African narrative – past and present.

Interviewed by The Georgia Straight, Maqoma said that after he and Sibisi saw a museum show about the choir in Johannesburg, “What hit them was the way that Black people are often treated when arriving on the shores of countries outside of their homelands.”

He said:

With Broken Chord we started with the story – we were legitimately interested in who these people were. And how Black people were shunned simply for being different. We soon realized that the work had the potential to speak to more than an individual story. The micro, in a way, became the macro. These singers, and how they were ostracised when they got to England, became how Black bodies are often ostracised when they are going to foreign spaces.

As we zoomed out there’s a thread connecting 1891 and now. . . .

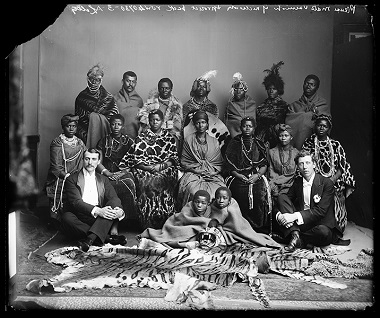

African Choir: London, 1891

Members of the African Native Choir; image from The Missing Chapter.

The Missing Chapter: Black Chronicles is a London-based archive research program which gathers “photographic portraiture to highlight diverse ‘black presences’ prior to 1948.”

It offers this straightforward account of the choir’s visit, along with the accompanying picture:

The African Choir was a group of 14 young men and women, and two children, from South Africa, then under British rule. . . .

The choir toured Britain between 1891 and 1893, ostensibly to raise funds to build a technical college on the Cape Coast, in order to support the expanding black labour force.

They were educated, devout Christians – several graduated from Lovedale College, a distinguished missionary school established by the Glasgow Missionary Society in the Eastern Cape Province.

They performed to great acclaim and large audiences at Crystal Palace, for members of the British aristocracy and leading political figures, and most notably for Queen Victoria at Osborne House, Isle of Wight.

Their stage repertoire was divided into two halves: one comprised Christian hymns sung in English together with popular operatic arias and choruses; the other traditional African hymns. The choir appeared in traditional African dress, and in contemporary Victorian dress in response.

Choir members such as Charlotte Maxeke (née Manye) and Paul Xiniwe later became leading social activists and reformers in South Africa.

Charlotte Maxeke

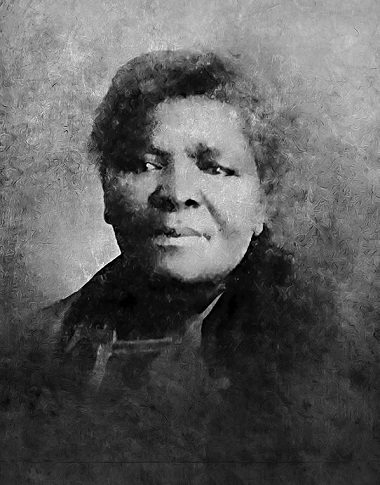

Charlotte Maxeke as a mature woman.

In commemoration of the birth of Charlotte Mannya Maxeke 150 years before, South Africa’s National Department of Sport, Arts and Culture named 2021 The Year of Charlotte Mannya Maxeke.

South African History Online featured Maxeke, describing her as “the ‘Mother of Black Freedom in South Africa.”

She was the only female delegate who had attended the founding of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC; later renamed the African National Congress or ANC) in Bloemfontein in 1912.

The article noted:

Sources state that the sisters [Charlotte was joined by her sister Katie on the 1891 tour] were uncomfortable with being treated as novelties in London and during this time Maxeke is said to have attended suffragette speeches by women such as Emmeline Pankhurst.

With hopes of pursuing an education, Maxeke went on a second tour to the United States of America with her church choir in 1894 (some sources state this date as 1896). When the tour collapsed, Maxeke stayed in the USA and studied at Wilberforce University in Cleveland, Ohio, which was controlled by the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AMEC).

At the university, she was taught under Pan-Africanist, W.E.B Du Bois, and received an education that was focused on developing her as a future missionary in Africa. . . .

After this, Maxeke and her husband established a school at Evaton on the Witwatersrand. The Maxekes went on to teach and evangelise in other places, including Thembuland in the Transkei under King Sabata Dalindyebo. It was here that Maxeke participated in the king’s court, a privilege unheard of for a woman. However, they finally settled in Johannesburg, where they became involved in political movements. . . .

As an early opponent of passes for Black women, Maxeke was politically active throughout her adult life. She helped organise the anti-pass movement in Bloemfontein in 1913 and founded the Bantu Women’s League of the SANNC in 1918.

Go here for the full article.

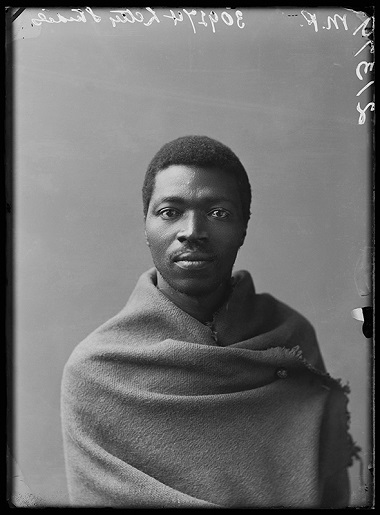

Paul Xiniwe

Paul Xiniwe became a leading figure in the precursor to the ANC; image from The Missing Chapter.

The Missing Chapter also featured Paul Xiniwe:

Paul Xiniwe (1857 – 1902) was a social entrepreneur, political leader and the most senior member of The African Choir.

A graduate of Lovedale College, he trained as a teacher and in 1884 presented a paper at the Native Educational Society, stressing that ‘the time had come for Africans to become members in Parliament.’

He became a member of the political organization Imbumba Yama Nyama, and later a leading figure of the South African Native Congress (which in 1912 became the African National Congress, and was instrumental in paving the way for the post-Apartheid state).

Together with his wife Eleanor Xiniwe, née Ndwanya, he opened the Temperance Hotel – the first hotel for black Africans – in 1894 in King Williams Town in the Cape Province. The couple had five children and were one of the most established families in the Cape, part of an educated social group actively engaged in national politics, and social change.

People like Maxeke and Xiniwe help to explain another phenomenon (which may relate to this show’s theme that Africans have not been taken seriously in the West). The growth of Christianity in sub-Saharan Africa in unequalled in history – but went largely unnoticed in the West throughout most of the 20th century.

In 1900 there were less than 10 million Christians there; now there are well over 600 million. The largest missionary conference ever, held in 1910 in Edinburgh, didn’t see this movement of God coming, and most of us in the West are still getting used to the fact that the weight of the church has shifted decisively to the southern hemisphere.

Broken Chord invites conversation

Broken Chord celebrates the African Native Choir’s tour while also illustrating underlying tensions between South Africa and Great Britain. Photo by Lolo Vasco

Broken Chord is primarily about dance and song, not about history. Musical director Sibisi described its purpose in a Vancouver Sun article:

The show includes some dialogue, but Sibisi says that it’s not there to create a narrative.

“We’ve tried to make the work as porous as possible. What is problematic about referencing the archive and trying to perform the archive is potentially becoming didactic or pointing fingers. At no point does the work try to convict somebody.

Rather, it invites people into the conversation. What we’ve tried to do is have the discourse come from an Afrocentric perspective. Because this is a story from Africa about Africans, it was important for us to have that perspective be what leads us to whatever resolution we think and hope we get to.”

Go here for the full article. The Georgia Straight and Vancouver Presents have also described well the artistic elements of the show.