C.S. Lewis was eclipsed at the time of his death (November 22, 1963) by the fact that John F. Kennedy and Aldous Huxley died on exactly the same day.

C.S. Lewis was eclipsed at the time of his death (November 22, 1963) by the fact that John F. Kennedy and Aldous Huxley died on exactly the same day.

However, he has retained a solid perch in the public consciousness, and for several good reasons. His Narnia series and theological works come to mind immediately; books about him and his legacy continue to appear at an impressive rate.

Ideas: C.S. Lewis and The Inklings

CBC Radio’s Ideas program will devote two hours (October 10 and 17) to C.S. Lewis and the The Inklings, the literary group (including J.R.R. Tolkien, Owen Barfield and Charles Williams) in which he was a central figure.

Many of the participants in the two-part series have close ties to the Inklings Institute of Canada – based at Trinity Western University – and to Regent College.

Participating in the Ideas discussion – which will focus on what Lewis and The Inklings’ understanding of what it meant to be fully human – are several members of the Inklings Institute: Ralph Wood, Malcolm Guite, Monika Hilder and Laurel Gasque (the latter two teach at TWU). All except Hilder have also taught at Regent College, and another contributor, Alister McGrath, has spent a considerable amount of time at Regent College over the years.

Alister McGrath has made something of a cottage industry of writing about C.S. Lewis (though one should not write him off as a one-trick pony; the Oxford professor has at least 50 books to his credit).

McGrath spoke at Regent College during the summer about his brand new C.S. Lewis: A Life. In response to the question, “Why has Lewis remained so interesting?” he pointed to four themes.

1. Christianity as a ‘big picture’

He quoted one of Lewis’s famous sayings: “I believe in Christianity as I believe that the sun has risen, not only because I see it, but because by it I see everything else.”

Lewis often stressed that we need to see in the right way, and to see further. We need to see what is in the shadows, and bring it into focus. Seeing this way allows us to fit things in.

2. Argument yields to vision

Referring to comments by Austin Farrar, a fellow scholar and friend of Lewis at Oxford, McGrath said: “Lewis makes us think we’re listening to an argument, but instead he’s giving us a vision, and that carries conviction.”

A key concept, for Lewis, was the ‘argument from desire,’ which posits, as Lewis said in Surprised By Joy, that “If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world.”

Another central belief is found in ‘The Weight of Glory,’ a sermon delivered at Oxford during the Second World War. Lewis said: “These things – the beauty, the memory of our own past – are good images of what we really desire; but if they are mistaken for the thing itself they turn into dumb idols, breaking the hearts of their worshippers. For they are not the thing itself; they are only the scent of a flower we have not found, the echo of a tune we have not heard, news from a country we have never yet visited.”

3. Imagination and stories

McGrath said Lewis increasingly came to see that fantasy literature allows reason and imagination to work together, and that his Narnia series is a “retelling of the Grand Narrative” – a fictional illustration that our own story is part of something grander.

“We live in a story-shaped world,” said McGrath, pointing out that one of the most important reasons Lewis has remained so successful is that “stories are more important than argument in a postmodern world.”

While celebrating Lewis’s continued significance in our time, McGrath also cautioned us that “Stories are also being told against us [by the likes of Philip Pullman]. We need to put forward a counter-vision; we haven’t had anyone to take Lewis’s place.”

McGrath devoted two chapters of A Life to the Narnia series, pointing out that Lewis created an imaginative world (“something produced by the human mind as it tries to respond to something greater than itself”) rather than an imaginary world (“something that has been falsely imagined, having no counterpart in reality”).

Lewis, he wrote, “takes ‘things that lie to hand,’ and puts them to use.” At the same time, drawing on his scholarship, he “drew extensively on ‘elements’ he found in literature.”

4. Translation

McGrath described Lewis as a “translator of the gospel message into modern terminology.” He believed that the requirement to translate complex material into simpler terms forces you to really understand your material. (See McGrath’s Mere Apologetics below.)

C.S. Lewis and his world, in books

Following are brief notes on some of the other recent books about C.S. Lewis, The Inklings, Oxford . . . that is, on various elements of the mystique which has lasted to the present day.

Colin Duriez: C.S. Lewis: A Biography of Friendship

Colin Duriez: C.S. Lewis: A Biography of Friendship

Like McGrath, Colin Duriez has written extensively on Lewis, and on J.R.R. Tolkien and their shared Oxford world. Lewis had a wide circle of friends, in academia, certainly, but also from childhood, from the army and among just plain folks.

Former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams described this “thoroughly researched, wide-ranging, sympathetic telling [of] Lewis’s story” as “allowing us to see him not as a solitary genius but as someone whose brilliance was always being honed and clarified in conversation and letter-writing and plain human affection.”

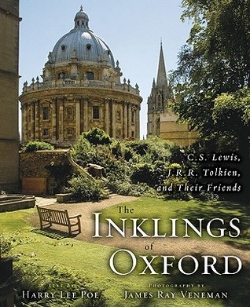

Harry Lee Poe: The Inklings of Oxford

Harry Lee Poe: The Inklings of Oxford

Subtitled ‘C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien and Their Friends,’ this beautifully photographed book shows more than it tells us about the Oxford milieu in which The Inklings met to drink beer at the fabled Eagle and Child Pub, debated theology, literature, Norse mythology in Lewis’s rooms at Magdalen College, and strolled together along the Cherwell River.

It was jolly fun, no doubt, but these meeting were also the crucible of literary works (The Lord of the Rings and the Narnia series to start) that still have an important place in our culture today.

Louis Markos: On the Shoulders of Hobbits

Louis Markos: On the Shoulders of Hobbits

Louis Markos reminds us that Lewis, like his old friend Tolkien, “sought, through critical essay and fantastic fiction alike, to restores stories to their proper place both as schools of virtue and repositories of truth.”

“Like Tolkien,” Markos says, Lewis achieved his goal “by spiriting his delighted audience away to his own magical world of talking animals and living trees where the old virtues and vices and the stock responses associated with them still existed.”

Devin Brown: The Christian World of the Hobbit

Though The Christian World of The Hobbit is focused on Tolkien’s fantasy story, Devin Brown quotes Lewis for his prescience a number of times.

Though The Christian World of The Hobbit is focused on Tolkien’s fantasy story, Devin Brown quotes Lewis for his prescience a number of times.

Reviewing The Hobbit in the October 2, 1937 issue of the Times Literary Supplement, Lewis notes that it “will be funniest to its youngest readers, and only years later, at a tenth or twentieth reading, will they begin to realize what deft scholarship and profound reflection have gone to make everything in it so ripe, so friendly, and in its own way so true.”

Brown says Lewis knew the role the ‘sacramental ordinary’ (following G.K. Chesterton’s view) had in Tolkien’s moral vision and fiction. In one essay, Lewis argued that “the value of the myth is that it takes all the things we know and restores them to the rich significance which has been hidden by the ‘veil of familiarity.'” In another, he said fairy tales “restore to [the actual world] something that has been eroded by the view, so dominant in the past century, that says it is nothing more than matter.”

Robert Boenig: C.S. Lewis and the Middle Ages

Robert Boenig: C.S. Lewis and the Middle Ages

In this scholarly work, Robert Boenig demonstrates the central significance of medieval literature on all elements of Lewis’s personal and literary worlds.

Catching up by mail with an old friend in 1935, Lewis referred to his relationship to his father before he died, then described himself in these three succinct sentences: “I am going bald. I am a Christian. Professionally I am chiefly a medievalist.” He finished his career as Cambridge’s first Professor of Medieval and Renaissance Literature.

Alister McGrath: The Intellectual World of C.S. Lewis

Alister McGrath: The Intellectual World of C.S. Lewis

This is an important companion to A Life, covering many of the kind of issues that were so central to Lewis’s life, but which the narrative flow of a general biography could not accommodate.

If there McGrath has an overarching concern, it is to “set Lewis in the greater context of the western literary and theological tradition . . . which he described as ‘the clean sea breeze of the centuries.'”

Alister McGrath: Mere Apologetics

Again Alister McGrath turns to C.S. Lewis – “perhaps the greatest Christian apologist of the 20th century” – as he encourages Christians to engage the culture around them.

Again Alister McGrath turns to C.S. Lewis – “perhaps the greatest Christian apologist of the 20th century” – as he encourages Christians to engage the culture around them.

And again he quotes Austin Farrar on Lewis: “His real power was not proof; it was depiction. There lived in his writings a Christian universe that could be both thought and felt, in which he was at home and in which he made his reader feel at home.”

Mere Apologetics goes beyond Lewis, but McGrath acknowledges his debt to the master throughout the book.

Heath McNease: The Weight of Glory / The Weight of Glory (hip hop remix)

Heath McNease: The Weight of Glory / The Weight of Glory (hip hop remix)

And now for something completely different. Heath McNease has put out two enjoyable CDs inspired by the work of C.S. Lewis. Both are available for free (donation requested) at Noisetrade,