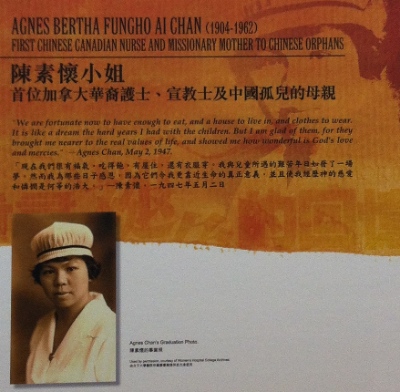

Agnes Chan was the first Chinese Canadian missionary nurse and mother to Chinese orphans. She herself had been born into a poor family in China, then sold a couple of times before finally ending up in the Chinese Rescue Home in Victoria. (Women’s Hospital College Archives)

Dr. Chung-Yan Joyce Chan (director of the North American Chinese Ministries Program at Carey) launched an exhibition and a book (Rediscover the Fading Memories) about ‘Early Chinese Canadian Christian History’ last fall.

The exhibition is showing at Regent College until April 12, and it is well worth taking in.

Joyce points out that the Christian church, though primarily a ‘white’ institution in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, “went against the predominant social ethos and touched thousands of lives of Chinese immigrants and their children, primarily through education.”

Churches aspired “to integrate . . . the ‘Orientals’ into Canadian society, to make them good citizens of the kingdom in heaven and on earth, and to ‘civilize’ them through the ethics of the Western church.”

Her project explores how the ministry of the church opened up opportunities for Chinese immigrants to receive quality education, to move beyond their social confinement and integrate into Canadian society. The exhibition offers inspiring profiles of doctors, nurses, pastors and other professionals who grew up in the church to become very productive members of Canadian society.

Following is an excerpt from the last chapter of Rediscover the Fading Memories.

The job of a historian is like a detective, trying to collect clues and figuring out relationships of collected data. We do not stop at recovering historical facts and data, but must go further to look at the implications of this information. In this final chapter, I will offer a few historical reflections on the Early Chinese Canadian Christian history we rediscover through this project.

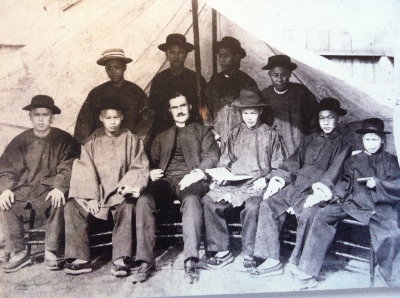

Rev. H.P. Hobson, first rector of Christ Church Cathedral in Vancouver, with a baptismal class ca. 1890. (Anglican Archives, Diocese of New Westminster)

First, this project prompted us to reconsider the question of identity: what it means to be a Chinese, a Canadian and a Christian, all at the same time. It’s easy for us to take the approach of excluding one identity from another and take the ‘either-or’ approach.

The lives of these early Chinese Canadian Christians demonstrated to us that it is possible to become and live in this trio-identity uniquely given by God and shaped by circumstances of their life journeys, though it required an extra effort to maintain a delicate balance of these identities.

The Chinese church was the centre for sharing the gospel – making faithful disciples of Christ – while at the same time a place for teaching the cultural heritage and cultivating a sense of social responsibilities toward Canadian society. Children of these early immigrants were raised in dual cultures through attending both Canadian and Chinese schools (in the church).

Many Chinese pastors at that period of time were also well versed Confucian scholars who had a passion to disseminate Chinese cultural values to the young people of the congregation. They taught the Bible as well as Chinese classics.

Despite serious discrimination from the mainstream society, both first and second generation Chinese Canadian Christians were not ashamed of their Chinese heritage and ethnicity, for they understood that was how God created them to be.

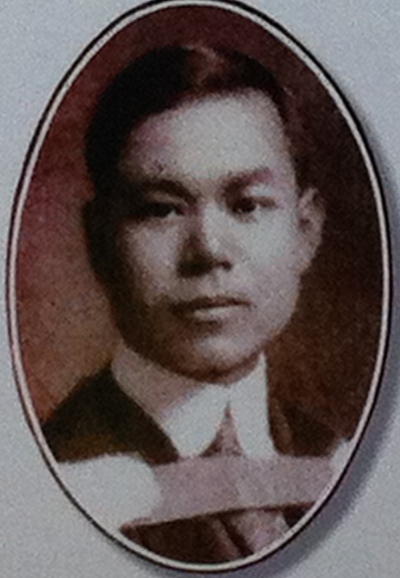

Philip Yuey Yit Chu arrived in Vancouver from China as a 13 year old fatherless boy in 1911. He served as a medical doctor in Vancouver and Toronto, with several years in China in between. (Chinese United Church, Vancouver)

Faithful citizens

Second, we see the desire of these early Chinese Canadian Christians to become faithful citizens of both the spiritual and earthly kingdom, a value much emphasized through the teachings of Caucasian missionaries. Ministry and spirituality went beyond the “four walls of the church.”

In fact, we see over and over again the unbreakable relationship between the church and its community.

As one lady remarked, “No one in the community did not know about our church and almost every immigrant and their children had gone through our church doors.”

Early Chinese Canadian churches made their presence known in the community and welcomed everyone who needed their assistance.

Regardless of whether people eventually become Christians (though it was certainly their hope), these churches shared the love of God through concrete community services and they acted as an advocate for the discriminated fellow Chinese.

Second generation Christians who received better educational opportunities and succeeded in their career did not forget that they had a mission to witness their faith in their professional roles. The concept of ministry was not confined to service within the church and spirituality meant much more than merely the pursuit of personal holiness.

In fact, quite a few early second generation Chinese Canadian Christians left the church because they were dissatisfied with the growing conservative evangelical emphasis which only focused on individual spiritual salvation rather than a holistic view of the Gospel.

They left the church and yet maintained a vibrant witness of their faith through community service built on the foundation of Christian values. They considered living out their faith in the other six days more true to the call as a follower of Jesus than just being a Sunday or church Christian.

With the ‘silent exodus’ of so many of our second generation from the ethnic churches, maybe it is time for us to reflect and learn from our history and reconsider the mission and identity of a Christian both individually and collectively. Now that we are not ghettoized by our cultural identity, we must not re-ghettoize ourselves and churches by our religious identity.

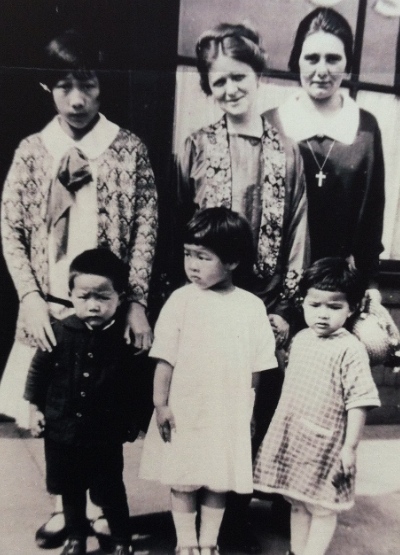

Hilda Hellaby and Bessie Field worked with Good Shepherd Anglican Mission in Vancouver. (Anglican Archives, Diocese of New Westminster)

Third, early Chinese Canadian churches/missions exhibited a strong ecumenical spirit, working together for the good of God’s kingdom.

While many of these early Chinese Canadian churches/missions provided the same kind of ministry programs and ‘services’ to the same target audiences, there was a strong desire to cooperate and work together rather than seeing each other as ‘competitors. in the ‘market.’

Many of them shared resources generously or collaborated with one another in their mission tasks. Churches were not worried about other churches ‘stealing sheep’ from their congregation because of their collaboration. Chinese pastors were often transferred from place to place in order to help out the most ‘needy congregations.’ The power of witnessing from the spirit of unity was evident.

Times have changed

Living in an age like ours, it is difficult for us to fathom the hardships which early Chinese Canadians encountered. In contrast to the early days, many Chinese Canadian churches nowadays consist of middle class and professional people. We do not need to worry about daily survival, discrimination, segregation and being deprived of certain privileges because we are immigrants.

Many immigrant children enjoyed status as ‘cream of the crop’ attached to their family well-being. As a result, we are raising a generation of comfortable Christians who run the risk of only enjoying ‘comfortable pews’ of the church.

The stories of our Chinese Canadian Christian pioneers call us to reexamine seriously our Christian commitment and calling as disciples of Christ. They taught us the meaning of the cost of discipleship; their lives offer us role models of excellence and faithfulness.

Remember the past

To borrow Winston Churchill’s words, “A nation that forgets its past has no future.” Many Chinese Canadian Christian leaders ask, “What is the future of our churches and our future generations?”

Maybe we should start looking at our past and gain some insights from those who have gone before us. Now it is time for us to stop and consider these questions: What kind of history are we creating for our next generations? What kind of spiritual legacy are we leaving behind for them?

We hope and pray that our next generations will see the unique opportunity and mission God has in store for us as Chinese Canadian Christians by looking at what God has accomplished through our ancestors of faith as well as through the way we live in this generation.

We hope that what our children see from the lives of Chinese Canadian churches are not cultural and generational conflicts between the Chinese and English congregations, but rather, how Christians of different cultures and generations live and serve with each other as a unified witness, as one body of Christ. May we learn to respect each other’s uniqueness and giftedness while at the same time helping each other to see our blind spots.

Finding the ‘Rediscover the Fading Memories’ exhibit takes a little looking, even after you are at Regent College on the UBC campus. Walk downstairs to the Allison Library, then thread your way through studying (and sleeping) bodies to the far left corner. A series of informative and interesting large poster boards with text and pictures about leading members of the Canadian Chinese Christian community during, primarily, the first half of last century stretches along two walls. The exhibit gives an illuminating glimpse into an important part of Canadian history.

Is the book still available for buying?

Hello Anne. I am not sure. Probably the best thing would be to contact Joyce Chan (https://zh.carey-edu.ca/2018/03/20/joyce-chan/) directly. Email: info@carey-edu.ca

Flyn Ritchie