Loren Wilkinson, surrounded by books and nature at his home on Galiano Island.

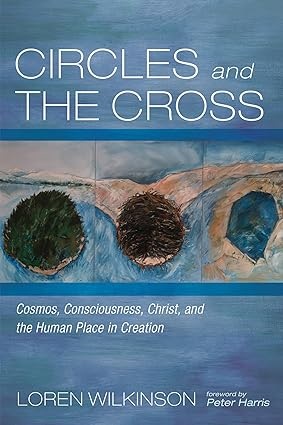

“. . . after a lifetime of deep commitment to the creation, cosmos and Christ, here is Loren’s most wonderful book.” Peter Harris, co-founder of A Rocha, wrote the Foreword to Loren Wilkinson’s Circles and the Cross: Cosmos, Consciousness, Christ and the Human Place in Creation (Cascade Books, August 2023)

Following is Loren’s Preface:

Circles and the Cross is an invitation to join me on a personal journey through two mysteries in the light of a third. Journeys need maps, and this book is a map through terrain that has been for me both difficult and delightful.

Cosmos is that first mystery: why is there something, and not nothing? And why should that ‘something’ be not chaos, but cosmos, which we experience – at least in this one tiny corner of it, the earth – as life-friendly and beautiful.

The second mystery is consciousness: why should this collection of stardust, which is myself, be an ‘I’ and not just an ‘it?’ The basic human response to that mystery is wonder. And from wonder grow the three great trees of human culture: art, science and worship.

Worship takes us to the third mystery, Christ. The word might prompt some readers to dismiss this book as ‘religious,’ but that would neglect the fact that no one is without religion. In the center of that word, the root (lig) suggests its importance. Re-lig-ion is related to the word ligament. Lig-aments hold us together, and just as we cannot live without ligaments, none of us can live without some sort of religion: a worldview or story that holds everything together.

Ultimately we have only two such religious stories. One says that the cosmos is a purposeful creation. The other says that it is a long, elaborate accident. Science grew out of that first story, belief in a Creator, but is often associated with the second story, belief in an accidental universe. So this book spends a great deal of time talking about science. It is written for religious people of both atheist and theist persuasions.

For over 40 years I have taught at Regent College, a graduate school of Christian studies affiliated with the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. I have been working on this book for over half of that time. Its long gestation can be explained in part by the sort of school Regent is, and in part by the awkwardness of the job I was given when I joined the faculty in 1981.

For over 40 years I have taught at Regent College, a graduate school of Christian studies affiliated with the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. I have been working on this book for over half of that time. Its long gestation can be explained in part by the sort of school Regent is, and in part by the awkwardness of the job I was given when I joined the faculty in 1981.

My title is ‘professor of philosophy and interdisciplinary studies.’ ‘Interdisciplinary studies’ has no content in itself (‘Philosophy’ was thrown in to make the title more respectable.)

An unkind but understandable description of interdisciplinary studies contrasts it with specialized disciplines, whose scholars are said to know more and more about less and less until they know practically everything about almost nothing. ‘Interdisciplinary’ scholars, on the other hand, are said to know less and less about more and more until they know practically nothing about almost everything.

And as C.S. Lewis has helpfully observed (in a long article on the word ‘Nature’), “‘Everything’ is a subject on which there is not much to be said.”3

On the other hand, a lot of effort has been expended in the last century on developing a ‘theory of everything’ in cosmology. As Wikipedia (that handy recent guide to ‘everything’) puts it, this cosmological search is looking for a theory “that fully links together and explains all aspects of the universe.”

The peculiar nature of Regent College is that it attempts to provide a sort of Christian ‘theory of everything’ to the adult students who come – from many parts of the world – with many kinds of professional training and experience (disciplines such as science, medicine, law and so on) and want an understanding of their faith that is at the same level as their professional training. That has been provided over the years by my superb colleagues through their expertise in more focussed disciplines such as biblical studies, theology and history.

It has been my task to help provide some of the ligaments that connect that theological knowledge with the world in which we all live. Over the years, I’ve come to realize that those connections require a kind of Christian theory of everything.

With much help from that rich community of colleagues and students, I’ve come increasingly to recognize that such a theory has always been there in the Christian story, implicit in the central belief that the Logos of the cosmos, “without which nothing was made that has been made” (John 1:3), “became flesh and blood and moved into the neighborhood” in Jesus (as Eugene Peterson, one of those Regent colleagues, put it in paraphrasing John 1:14).4

That Christian theory of everything is given a clear statement by Paul when (in a passage that uses ta panta, the Greek word for ‘everything,’ six times) he says that the Creator’s purpose is to bring everything to reconciliation with God through Christ (Col 1:15–19).

These years of teaching and writing have given me the great privilege to learn and share that theory of everything in a world of people who desperately need such a theory to hold their life together. Time spent in Scotland (as I explain in my introduction) helped me to appreciate the powerful symbolism of the Celtic cross: that image of the suffering love of God at the center of the circles of both cosmos and consciousness.

The cross gives us our clearest picture of the character of the triune Creator of all things. That character is best summed up in Paul’s letter to the Philippians when he urges them to have the mind of Christ who, being equal with God, “emptied himself.”5

The Greek word translated as ’emptied’ gives us the term kenosis. What kenosis implies for Creator, cosmos and consciousness is the central question that Circles and the Cross seeks to explore.

This journey of exploration ranges widely, covering terrain as different as Neolithic culture, medieval philosophy, the Enlightenment, Romanticism, the birth of the environmental movement and the complexities and confusions of the twenty-first century. We will have guides as diverse as St. Francis, Duns Scotus, Johannes Kepler, William Wordsworth, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Aldo Leopold and Iain McGilchrist.

Loren and Mary Ruth Wilkinson with the almost-completed book this spring.

This is also a very personal journey, touching lightly on my own story, which begins on a riverfront farm on the remnants of the frontier in Oregon, continues through years of education and finally comes to Regent College and a shared waterfront farm on an island in British Columbia.

My wife, Mary Ruth, joined me in that journey during college; our twin children, Heidi and Erik, a bit later. Our life together traverses most of the history of what has come to be called ‘the environmental movement,’ and much of the teaching that Mary Ruth and I have shared has been about trying to show how the concerns of that movement can be understood most fully within the Christian story.

I invite you to join us on this journey

3. Lewis, ‘Nature,’ Studies in Words, 37.

4. Peterson, The Message.

5. Phil 2:7 (NASB), emphasis added.

The Preface to Circles and the Cross is re-posted here with the author’s permission.

Regent College Bookstore will host a book launch with Loren at Regent College December 7.