News stories about foreign interference turn up with alarming frequency these days.

News stories about foreign interference turn up with alarming frequency these days.

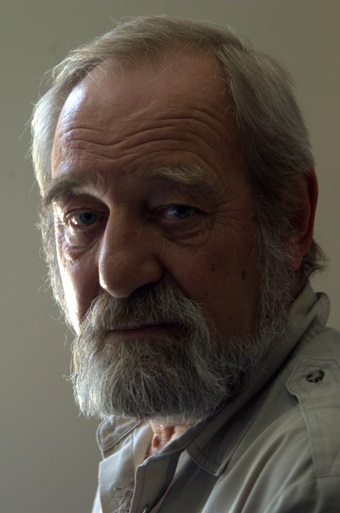

Jonathan Manthorpe is not surprised – certainly not when it comes to China – but he does take some comfort in the fact that the general public and, maybe, finally, political elites are paying attention.

He can take some of the credit for our increased awareness of China’s malign intentions.

When Claws of the Panda was published in 2019, I wrote about it, both because it was so timely and relevant to Vancouver, and because of the book’s surprising attention to our missionary legacy and its influence on Canada’s relationship to China.

Now Cormorant Books has published an expanded and updated version of Claws of the Panda.

Much of the material is the same, but five new chapters, more than 70 pages, have been added.

And the theme suggested by the subtitle – ‘Beijing’s Campaign of Influence and Intimidation in Canada’ – has only been strengthened. Manthorpe’s well-researched and cogent arguments continue to convince.

I will briefly introduce the new version of Claws of the Panda, then follow up with my original review (which has some interesting insights about the influence of missionaries on the history of Canadian relations with China).

Manthorpe is very critical of Canada’s diplomatic and political responses to Chinese, seeing them as naive at best. He is not impressed by the ongoing Foreign Interference Commission headed by Justice Marie-Josée Hogue, whose first report was released May 3.

Asked about the Commission by journalist Paul Wells in a May 1 podcast, he said:

It’s irrelevant . . . it’s the wrong question. Actually, it makes me quite angry because here we have had the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, we’ve had Canadians of Chinese and Tibetan and Uyghur heritage for decades . . . warning about influence and intimidation here. . . . And the first time the Members of Parliament get up on their hind legs and start screaming is when it involves allegations of election interfering.

(Manthorpe has another book coming out this week, which is, apparently, not flattering about the state of Canadian democracy.)

He continued by saying the government should have three priorities:

- “The intimidation of Canadians of Chinese heritage”;

- “Our universities . . . Beijing is sending military scientists masquerading as graduate students to pilfer . . . weapons technology”;

- “How do we change the culture amongst our captured elites.”

He wrote in the Vancouver Sun May 3:

He wrote in the Vancouver Sun May 3:

Today, the real problem of Beijing’s campaign of influence and intimidation in Canadian life isn’t in Parliament and national elections. It’s among the communities of Canadians of ethnic Chinese heritage and the many minority people subjugated by Beijing.

And it’s in the culture of self-delusion among our politicians, senior officials, business people and academics who continue to believe that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) holds a special affection for Canada.

As I set out in Claws of the Panda: Beijing’s Campaign of Influence and Intimidation in Canada, it started in China in the 1940s when the CCP came across Canadian missionaries and diplomats.

The party quickly realized that many of them were influential back home, but were naïve in the extreme. They could be cultivated and give the People’s Republic of China (PRC) access to the industrialized world and to Canada’s neighbour, the U.S.

And so it was. In the 1960s and onwards the PRC gained almost unfettered access to Canadian industrial and military technology through universities and academic institutes, to the country’s natural and agricultural resources, and an almost iron-cast guarantee of Canadian diplomatic support for Beijing on the international stage.

He has more confidence in the general public, stating in Claws of the Panda:

The Huawei Affair, coupled with Beijing’s duplicitous response to the COVID-19 pandemic, caused a massive swing in Canadians’ view of China. In 2002, only 23 percent of Canadians had a negative view of the PRC. In 2020, that dark assessment rocketed to 73 percent, and has remained around that number since.

He summed up:

There was always going to be a tectonic crisis in the relationship between Canada and China. If not the Huawei Affair, it would have been something else that exposed what was an ultimately untenable relationship. The storyline peddled by Canada’s self-deluded establishment of a benign, productive relationship with the Beijing regime was never sustainable.

The [Chinese Communist Party’s] ultimate power flows from its innate capacity for thuggery, and that will not change. What is unforgiveable is that it took Beijing’s vile, measured, inhuman and persistent abuse of Michael Spavor, Michael Kovrig, and their families and friends to finally rip the blinkers from the eyes of Canada’s panda huggers.

Manthorpe believes Canada is being forced to re-evaluate its place in the world and its national security interests. And he is rightly being given credit for having played a significant role in shaping that re-evaluation.

Speaking with Wells, Manthorpe agreed that it was a bit frustrating that his book came out in early 2019, just a couple of weeks after Meng Wanzhou was arrested. But he added: “What the book does, and did and continues to do, was to provide the context for what happened.”

Although Claws of the Panda deals with Canada-China issues, it is particularly relevant to Metro Vancouver. Not only do we have a very large Chinese-Canadian population, but Meng Wanzhou was arrested and held here and Kevin and Julia Garratt – a Christian couple also held hostage in China, and referred to in the book – live in the area. Manthorpe himself lives in Victoria.

My 2019 review

Hardly a day goes by without news reports about the troubled relationship between Canada and China – Meng Wanzhou and Huawei, Canadians held in prison, canola trade, money laundering.

Hardly a day goes by without news reports about the troubled relationship between Canada and China – Meng Wanzhou and Huawei, Canadians held in prison, canola trade, money laundering.

Pundits debate whether we should stand up to China, whether we are being used by the United States as a pawn between superpowers, whether we should just focus on developing trade with China . . .

Claws of the Panda offers some timely insights for anyone following these issues. Subtitled ‘Beijing’s Campaign of Influence and Intimidation in Canada,’ the book does an admirable job of providing context for the ongoing flurry of reports.

Author Jonathan Manthorpe is a veteran journalist with 50 years of experience as a foreign correspondent in Asia, Africa and Europe, now based in Victoria.

Former ambassador to China David Mulroney says of the book:

Manthorpe’s account of China’s clandestine efforts to influence people and politics in Canada is as compelling as it is disturbing. This is an important book for anyone who wants to understand China’s growing influence in Canada.

Missionaries, surprisingly, receive quite a bit of attention in Claws of the Panda, from the first line on the inside flap (“Canada’s long relationship with the People’s Republic of China – first based on missionary zeal, followed by diplomacy and trade . . .”) to the Epilogue’s chapter heading (“Time to abandon the missionary spirit”).

The threat

But first a bit more about the main thrust of the book. Here is an excerpt from page one:

Much of this book is about how the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is running roughshod over Canadian values and interfering in Canadian internal affairs to a degree that sometimes amounts to a challenge to Canadians’ sovereignty within their own country.

But this is not a book arguing that Canada should distance itself from the current regime in Beijing. As China under the leadership of President Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party sees itself re-emerging as the world’s natural, irreplaceable superpower after two centuries of “humiliation” at the hands of Western nations, engagement with China cannot and should not be avoided.

But what the sad and often difficult story of Canada’s 150 years of involvement with China tells us is that we need to find a less self-delusional, more courageous and more intelligent way of dealing with the new version of the Middle Kingdom. If Canada does not redress and rework its approach to Beijing, this country may be steamrollered by the juggernaut of history.

Jonathan Manthorpe

The first two chapters explain why and how “Canada has become a battleground on which the Chinese Communist Party seeks to terrorize, humiliate and neuter its opponents”.

Chapter One describes China’s determination to battle the ‘Five Poisonous Groups’ – “advocates for independence for Tibet, Xinjiang and Taiwan, promoters of democracy in China and adherents of Falun Gong.” Manthorpe gives specific examples of harassment in Canada, and of violent physical attacks and imprisonment in China.

Chapter Two, ‘The Hundred Strategies to Frustrate Enemy Forces,’ examines “the machinery that the Chinese Community Party has fashioned to control, influence and milk its relationships with foreign countries.”

Most of the rest of the book considers the history of Canada-China relations in some detail, from ‘Chinese Build Canada; Canadians Save China’ on to very current events (Claws of the Panda was published early this year).

A recurrent theme is that politicians and the public have consistently taken an unduly optimistic view of those relations. While public opinion has soured considerably towards China, Manthorpe fears there is not yet enough political will to address the dangers posed by the rising superpower.

He provides background on Huawei, which is particularly important in Vancouver as Meng Wanzhou is being detained here. But he says, “The Huawei story was not the only indication that public skepticism was pushing a sea change in the Liberal government’s attitude toward the activities of corporate tentacles of the CCP regime,” providing insights on several other Chinese corporations (Nexen, O-Net Communications, Hytera Communications, China Communications Construction Company, etc) which have gained, or have sought to gain, a foothold in Canada.

Claws of the Panda provides the substance which is usually missing in news coverage. Consider this quote, which is followed up in detail:

Canada has continued to be useful to the CCP and its extended family among the red aristocracy, though not as a partner – more as an ATM and safe deposit box for money laundering.

Manthorpe points out that we are facing a double whammy when it comes to China – even as we are being infiltrated and harassed, we are actually losing ground:

Canada’s importance in the eyes of the CCP shrank quickly in the 1980s and 1990s as other countries found themselves orbiting closer to China’s sun. This change is evident in the trade figures. Canada was China’s fourth largest trading partner at the time of mutual diplomatic recognition in 1970. By 2016, Canada ranked twenty-first, and it is continuing to sink.

Canada has served its purpose, opening the door to global society in the 1970s and ending the CCP’s international purgatory after the Tiananmen Square massacre . . .

That is not the way the ‘Mish Kids’ would have liked to see things go.

Missionary zeal

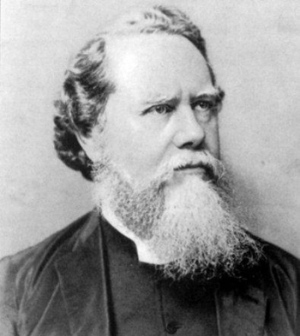

Hudson Taylor was key to kindling Canadian missionary interest in China.

I had not expected to read about James Hudson Taylor in a book warning us about China’s current influence on Canada, but Manthorpe devotes considerable attention to his role in birthing missionary enthusiasm for China.

Having founded the China Inland Mission in 1865, he “decided to use the newly opened Canadian Pacific Railway to shorten his journey back to his home in China after a visit to Great Britain.”

Though he initially had no desire to plant his work in North America, his reception changed his mind:

After a couple of weeks in Canada, Taylor observed “such deep wellsprings” [quoting from Alvyn Austin] of missionary enthusiasm that he set up a North American branch of the China Inland Mission in Toronto.

Taylor’s visit coincided with a generational change in Canadian religious communities that saw the advent of an era of militant evangelism coupled with a strong belief in the Christian responsibility to promote social reform.

By the time Taylor continued on from Ontario, he had received strong financial support along with 42 applications; he chose 15 to accompany him:

On a damp September evening, about a thousand young people carrying torches marched down Toronto’s Yonge Street to Union Station to see off Taylor and his band of Canadian missionaries. [!] Over the course of the next 60 years, approximately 500 Methodist missionaries went to live and work in western China. Their children remain active to this day through organizations such as Missionary Kids and the Canadian School in West China.

Manthorpe explains the long-term implications:

Thus, the missionaries and their offspring, brought up in China, fluent in the language and cultures – the so-called Mish Kids – were instrumental in shaping public support for the early recognition of the People’s Republic of China after the Communist Party took power in 1949.

Sympathy for the CCP among the Mish Kids stemmed from two sources: antipathy toward the neo-fascist Kuomintang and politically left of centre interpretations of Christianity among Methodists and the United Church of Canada.

The Mish Kids and other scions of the Methodists, in particular, had a significant presence in the Department of External Affairs in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s. They also played major roles in the evolution of Canada’s independent foreign policy after the Second World War.

Significant figures such as James Endicott, Arthur Menzies, Paul Lin and Chester Ronning (note the subtitle in the book pictured) are discussed in some detail.

Significant figures such as James Endicott, Arthur Menzies, Paul Lin and Chester Ronning (note the subtitle in the book pictured) are discussed in some detail.

I daresay Manthorpe’s assessment of missionary influence will come as a surprise to many – both to secular observers who discount religious influence on much of anything and on current supporters of missionary enterprises, most of whom who not have much sympathy with the deeply anti-Christian record of the Communist Party of China.

Though Claws of the Panda offers a wide range of helpful insights, I do have a couple of caveats.

First, a quibble about editing. While Manthorpe rightly refers to the pioneering work of Andy Yan, head of SFU’s City Program, on Vancouver’s dysfunctional housing market, he misspells his name (Andy Yam, page 206) and doesn’t refer to him in the index.

The second is a matter of assessment. He states:

Canada’s fascination with China surfaced in the 1880s, when this country began to send Christian missionaries across the Pacific. Then, as now, China appeared to be a vast market just waiting to gobble up what Canada had to sell. However, the belief that Chinese would rush to become Christians was just as much of an illusion as the conviction today that Chinese yearn to buy Canadian manufactured goods if they have the chance. . . .

That belief, that Canada could change China by the self-evident appeal of Canadian values, remains deeply embedded even today. Events in China show this view to be delusional.

Manthorpe’s warnings about China’s threat to Canada are timely and astute, but it is worth remembering that he and many others have underestimated the growth of Christianity in China. While it is true that Chinese people did not flock to Christianity immediately, there are now, by most reports, some 100 million Christians in China.

The missionaries’ work was not in vain. And who knows, maybe the Mish Kids’ – and Canada’s – influence may be greater in the long run than we can see now.

Thank you, Flyn, for your discernment and commentary about this remarkable book.