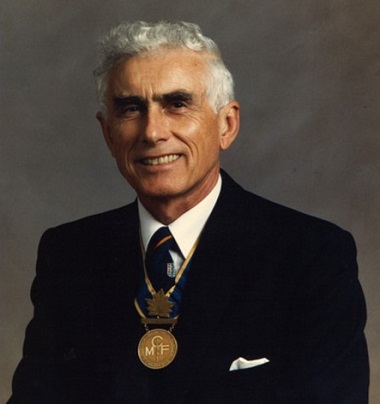

Dr. Donald Watt was remembered for his work in medical missions, both in the field and in administration.

Family and friends celebrated the life of a key figure in the history of United Church medical missions in Abbotsford February 2.

Dr. Donald Watt (November 14, 1924 – December 29, 2018) passed away in his sleep at the age of 94, following a productive and often adventurous life.

He did pioneer work in several small, remote BC hospitals with his wife June and their four children, before taking on senior administrative roles with the network of hospitals (much of the time based in Vancouver) and spending his last few years in Abbotsford.

During the Service of Remembrance and Celebration at Trinity United Memorial Church, two of Watt’s children, Elizabeth and David Watt, said that as a young man who had trained in the Royal Canadian Air Force at the end of the war and gained his medical degree from the University of Toronto in 1950, he was seeking out what his future should be .

“He woke up one night,” said Elizabeth, “and a voice in his head was saying, ‘Go to the Queen Charlottes.'” Apparently the great fishing he knew was available helped to confirm the call; his older brother Arthur had already spent a summer as a medical student at Bella Bella.

The mission hospitals already had a rich history by the time Watt drove west with his new bride June in 1951 (spending just $63 on gas and $30 on food for the week-long trip – one of many signs of Scottish thrift, apparently).

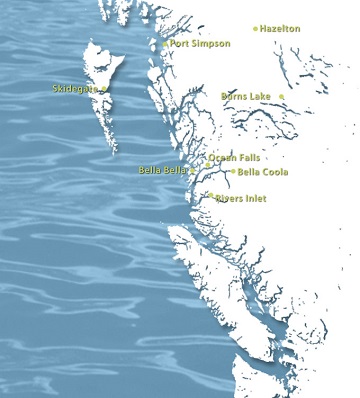

A map of medical missions in BC from the United Church Archives.

Neil Semple, in his encyclopedic history of Methodism (one of the founding denominations in the United Church merger in 1925) The Lord’s Dominion, stated:

Perhaps the most innovative work centred on the development of medical facilities for the native bands. In British Columbia, the Missionary Society eventually supported five hospitals at Fort Simpson, Bella Bella (R.W. Large Memorial), River’s Inlet, Port Essington and Hazelton (H.C. Wrinch).”

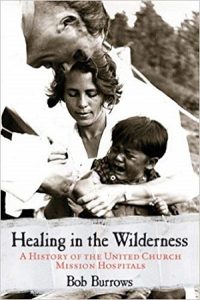

Bob Burrows amplified the theme in his book, Healing in the Wilderness: A History of the United Church Mission Hospitals.

Speaking of the early days (1889 – 1914) he described the work of pioneering medical missionary Dr. George Darby, including his surgery on a lone trapper attacked by a grizzly near the head of Rivers Inlet. It took the wounded man eight days to make the arduous 80 mile trip to the mission hospital at Bella Bella.

Burrows, who himself worked in BC as a minister and captain of a missions boat, asked:

How is it that so long ago, in such a wilderness, there were skilled doctors and nurses able and willing to provide medical care? Part of the answer is found in the history of the Methodist Church in Canada. As far back as 1874, the Methodists had made the decision to reach out to the people on the north coast of British Columbia. . . .

While on furlough in Eastern Canada in 1888, Thomas Crosby spoke at many meetings and church services, telling of his adventures and describing the needs of the isolated settlements he was serving. He was particularly concerned that there were no medical services available anywhere on the coast north of Nanaimo on Vancouver Island.

Some of the young physicians who had hoped to become missionaries in China, but who were prevented by the political unrest there and the lack of church funds, went instead to serve in BC.

Dave and Elizabeth Watt. Dave described his parents as “amazing pioneers and wonderful role models.”

Northern BC was not quite as much a frontier by the 1950s, but there was still plenty of pioneering work to do. Following is the account of Dr. Watt’s life sent out by the BC Conference of the United Church of Canada:

An avid fisherman who was eager to work for Canadian mission hospitals, Don was happy to be sent to the west coast of Canada where he spent the next 38 years working for the United Church of Canada (UCC) Board of Home Missions, with June volunteering at his side.

Don was placed as the lone MD on the Queen Charlotte Islands (now Haida Gwaii) in 1952, and acted as Coroner, Justice of the Peace and Public Health officer, while June volunteered her time working 12 hour nursing shifts, teaching prenatal classes, assisting Don in the OR and helping with hospital staff morale.

Don set up clinics in Sandspit, Skidegate Village, Masset and logging camps at Juskatla and Cumshewa Inlets, travelling by plane, boat and truck, and using innovative ways of communication that he had developed in the pre-pager era.

His practice included surgery and drop ether anesthesia, and hiking into camps and the surrounding woods to stabilize accident victims. He facilitated the building of the 21-bed Queen Charlotte City (QCC) hospital which opened in 1955.

Don was transferred to the Bella Coola General Hospital in 1956, where he spent the next seven years as physician and Hospital Superintendent. Working from the Thomas Crosby church boat; he also provided medical care to lighthouses and remote logging camps in the area.

Care of victims mauled by grizzly bears and horseback riding into the mountains to stabilize accident victims soon became part of his medical life. Don was later adopted into the Nuxalk (Bella Coola) Nation by the Walkus and Edgar families, and given the names “Nooskumiich (one who heals with his hands) and Nenetsmlayc” (one who brings back to life) in celebration of the opening of the new Bella Coola hospital in 1980.

Although reluctant to leave the full-time practice of medicine, Don accepted the position of Medical Superintendent for the UCC hospitals in BC and moved to Prince Rupert in 1963. The following year, he became Medical Superintendent for all UCC hospitals across Canada, and moved June and their four children (all delivered by Don) to Vancouver.

Pictures of Don Watt’s family and work were shown at the reception.

Don was an active recruiter and gifted orator for the UCC hospitals. He facilitated and negotiated the building of new hospitals and the acquisition of new equipment wherever the UCC had outposts or hospitals. He ensured that the sites were always well staffed, and he encouraged local health care education and hiring, as well as local representation on the hospital boards.

Dave and Elizabeth Watt recalled several incidents from their childhood, including singing hymns Sunday evenings, with June playing the piano and looking after the four young kids. Dave described his father as a quiet Christian and his parents as “amazing pioneers and wonderful role models.”

When Burrows wrote Healing the Wilderness in 2004, the heyday of United Church medical missions was already past. He said:

In 1939 there had been 24 hospitals administered by the United Church of Canada. By 1964, when Dr. Donald Watt was appointed superintendent of hospitals and medical work, the church was operating only 10. And by the end of the next 25-year period, in 1989, There would be just five.

Clearly the landscape was changing, and for a variety of reasons. The trend toward community acceptance of responsibility for local hospitals that had begun in the 1940s had continued through the next three decades

Support from provincial governments had encouraged municipalities to renew or expand their health facilities and services. Larger centres had added to their medical capacities, thereby attracting more patients from rural communities, and changing demographics had made it impractical to provide full hospital services for smaller populations.

The final factor was the church’s growing difficulty in attracting and retaining nurses and doctors in the isolated communities served by church hospitals.

Healing in the Wilderness is well worth reading. Reviewing the book in BC Studies, Norman Knowles questioned some of Burrow’s “lack of critical perspective,” but concluded with these words:

Healing in the Wilderness is well worth reading. Reviewing the book in BC Studies, Norman Knowles questioned some of Burrow’s “lack of critical perspective,” but concluded with these words:

Despite these limitations in analysis, Healing in the Wilderness is a well-written work that will be of interest to anyone wishing to learn more about the history of medical missions and the delivery of rural health care services.

British Columbians with an interest in local history will find the histories of the United Church’s long-standing medical missions on the north coast and in the central interior especially informative.

Burrows devoted a whole chapter of Healing in the Wilderness to Watt, concluding with these words:

Though [Watt’s] father and two brothers were all ordained ministers in the United Church, Donald Watt, MD, FCFP, was not ordained but lived out a Christian ministry of great worth to patients who received his skilled care, to the generation of doctors and nurses he recruited and supported, to the people directly affected by his wise oversight and to the church that was privileged to be his employer.

Don and June Watt attended St. Steven’s United Church in Vancouver for several decades. June passed away after they had been married 57 years. Don lived in Abbotsford for the last six years of his life, attending Trinity Memorial United Church.

The Bob Stewart Archives of the Pacific Mountain Region of the United Church of Canada links to an interview (and transcript) from 2012 in which:

Dr. Watt speaks about his early aspirations and influences and the lessons he learned along the way. With characteristic good humour, he gives some insightful and sometimes entertaining anecdotes of providing medical care in isolated regions of Canada.

Thank you for sharing this story of Dr. Watt. I was born in the ‘new’ Queen Charlotte City hospital in 1956 and Dr Watt was the one who helped my mother bring me into this wonderful world. He worked with my father, Rev. Lloyd Hooper for many years and he was a family friend. A wonderful Christian gentleman.

To his family, I offer my heartfelt condolences.

Blessings,

Mimi (Hooper) Zuyderduyn

My first job after graduating from Dental Assisting was at Wrinch Memorial in Hazelton from 1974 to 1979. Dr. Watt interviewed me in Toronto and gave me, a very young 19 year old, a chance to get started on a new journey in life. I remember he took the time to meet with my parents as well after the interview, reassuring them about my decision.

Over the next five years in Hazelton it was always a pleasure when Dr. Watt and his daughters Vicky and Elizabeth came to visit.

My sincere condolences to the family.

Jo Ann Malysh (Gibson)

I worked at the Wrinch Memorial Hospital in Hazelton from 1962-65 and 69-70; plus 77-84, Bella Coola for a relief month in 1964 and 1984-87, plus three years in Baie Verte Newfoundland. Many times I had the privilege of working with Don as he ‘helped out’ when local physicians were away. He was always wonderful to work with.

Another amazing event was the fact that his wife, June and I were both honoured with the Volunteer Award in Ottawa in 1985! In 1964 when travelling from Hazelton to Bella Coola to do relief nursing, Don picked me up at the train station in Prince Rupert and I spent a memorable evening with Don and June before boarding the Northland Prince to travel to Bella Coola!

Our condolences to the family and thanks Elizabeth for writing to me.

Thank you for this wonderful story about Dr. Don Watts. He was a man of energy, kindness and (if you excuse the old-fashioned terms) a gentleman and a true churchman.

As we learn more and more of the severe damage the settler culture did to the indigenous cultures, we are also reminded of people of real caring, who offered the skill, openness and compassion of their hearts in the work they did. Don was a real friend to many and well-appreciated by all he treated.

We remember Don because his life is worth remembering . . . and we remember him so that we might be encouraged to “go and do likewise.”

To Don’s family: our prayers and hearts are with you in your loss.

– Doug Goodwin

This is a wonderful tribute to our old friend Dr. Donald Watt. He recruited my girlfriend and myself in London ON., in the 60’s. We worked full time at Queen Charlotte Islands Gen Hospital from Dec 2, 1967 – Dec 4, 1978. It was a privilege to work with and know Don. He was creative, innovative, supportive, kind and competent and so passionate about good patient care. Work was fun when he was around.

My condolences to his family.

Barbara