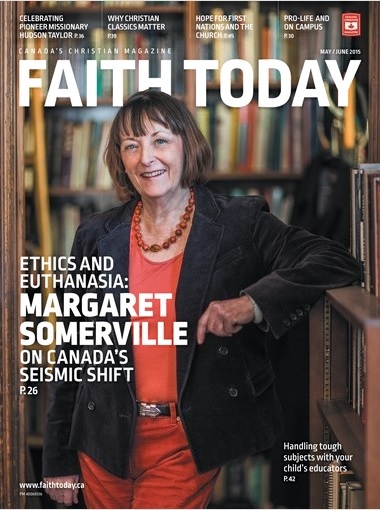

High-profile ethicist Dr. Margaret Somerville will be the guest speaker at the Christian Advocacy Society’s 25th annual Celebration Dinner at Bethany Baptist Church this Saturday (November 21). Karen Stiller of Faith Today magazine interviewed her earlier this year. Following is her introduction and a portion of the interview:

High-profile ethicist Dr. Margaret Somerville will be the guest speaker at the Christian Advocacy Society’s 25th annual Celebration Dinner at Bethany Baptist Church this Saturday (November 21). Karen Stiller of Faith Today magazine interviewed her earlier this year. Following is her introduction and a portion of the interview:

If you tend toward the “conservative” side of life – as labelled by others, probably – you likely know how rare it is to open a newspaper and see your viewpoint on issues such as religious freedom and euthanasia reasoned out by a high-profile columnist.

Margaret Somerville does just that. She is not without controversy. The Australian-born professor with positions in both the faculties of law and medicine at McGill University in Montreal cannot be easily categorized, to the chagrin of many.

Her views often align with a Christian ethical way of looking at the world, yet she does not place herself easily in that camp. She writes widely on issues Christians tend to care about, almost inevitably providing a counterargument to the spirit of the day.

In our cover story we interviewed Somerville about her views on a current hot topic, euthanasia, but also how she sees herself fitting into Canada’s cantankerous public square.

Faith Today: With euthanasia specifically, it seems we can’t assume a person of faith will necessarily be against it.

Margaret Somerville: We have in ethics what we call the ethical yuck factor – when we first hear about something, we have an unconscious way of reacting to whether or not something is ethical. When you walk up to somebody and say, “Do you think doctors should be able to kill their patients?” It’s a moral intuition, an emotional reaction that warns us there is something wrong.

But if you do surveys and you don’t use the word euthanasia or killing, and you make it a nice thing someone in a white coat will do, and you call it kindness and mercy, and you call the alternative cruelty, then it sounds okay. You’ve coated all those original moral intuitions and emotions that tell you this is wrong.

There is a lot of wariness of ever using the Nazis as an example, but it is a relevant question of how those Nazi doctors could do what they did. You can sugarcoat evil. You can get used to it. As familiarity increases, the ethical warning signs decrease.

FT: You hear the argument for euthanasia that we are kinder to our dogs when they are suffering. That seems to sum up some kind of the acceptance out there toward euthanasia to humans who are suffering.

MS: Whether you believe in human exceptionalism matters – that humans are different in kind from other animals – or are we just different in degree?

I believe that not seeing humans as special in some ways is currently the world’s most dangerous idea. If you’d do it to your dog, you’d do it to your mother. I think this is the single, biggest values-ethical-moral-philosophical decision of the 21st century, if we legalize euthanasia.

I can’t believe the Supreme Court has done this. I was asked to help draft legislation, only by people who are concerned about it, not by the government. I wrote a letter to [Justice Minister] Peter MacKay and said you can’t go with this. I thought he should use the notwithstanding clause.

It is a momentous decision. It’s a seismic shift in our most important foundational values, the respect for life.

FT: What would you want to see happen with the legislation around euthanasia that is being developed?

MS: Will we bring in legislation that is very restrictive? I wish we weren’t having this discussion at all. Even recognizing it’s okay to kill your patient is terrible.

But if we’re going to have it, and this is the reality now, I think that we have to be very clear where it could apply. It should only apply in the most rare and narrow of circumstances. It has to have all kinds of procedural safeguards, like you can never give an injection without the express individual permission of a court.

If you go back to the Rodriguez case [Rodriguez v. British Columbia, 1993], chief justice Beverley McLachlin was in the minority. She said we safeguard this by requiring judicial regulation. We can quote her as saying this is what we need.

If you were to lock someone up in a psychiatric institution for a few hours, you’d have to get court authorization. All of those things say when it is a very, very serious decision, you can’t just make it for yourself. That would be one of the things I would require.

You have to be able to offer people totally adequate palliative care that includes full pain management. It’s a disgrace in all our Western democracy that we don’t do that. I’ve been heavily involved in advocating that it is a breach of fundamental human rights for a health care professional to leave someone in serious pain.

FT: Do you believe if we had better palliative care, the demand for euthanasia would not be as strong?

MS: It would decrease in practice when people get good palliative care. A very large percentage decide they don’t want euthanasia – research tells us this. Not all, but most.

The other thing is that legally you can’t get informed consent to assisted suicide or euthanasia unless you have offered a person alternatives. You have to have good palliative care in order to obtain informed consent.

The end-of-life so-called care act in Quebec [Bill 52] says you do not have to have palliative care, and the Canadian Medical Association in the brief they put into the Supreme Court expressly said it was not a condition that you have palliative care to have access to physician-assisted death. That is shocking.

I try not to be cynical. I call cynicism secular society’s major moral shortcoming.

FT: Thank you, Margaret.

For the full interview go here.

On October 29, more than 30 Christian denominations together with more than 20 Jewish and Muslim leaders from across Canada endorsed the Declaration on Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide.