How the world can change in just a few days!

How the world can change in just a few days!

As the seriousness of the global situation began to sink in towards the end of last week, more and more governments announced increasingly stringent measures to fight the spread of the COVID-19 virus.

Schools, restaurants, museums, churches, concerts and conferences have been closed, cancelled or severely restricted on a scale more global than ever before in living memory. (I would have been at a St. Matthew’s Passion concert as I am writing this, had it not been cancelled.)

Although more spread out than the September 11 tragedy, Corona’s long-term legacy will claim many more lives and threaten many more jobs globally than the event that supposedly ‘changed everything,’ causing 3,000 deaths and 6,000 injuries.

Sacrifice in China

Dr. Li Wenliang

Just over two months after the virus was first identified in Wuhan, a Chinese city of around 10 million most of us had never heard of, over 160,000 infections have been reported (over half having now recovered) and more than 6,000 deaths.

One of the earliest victims was Dr. Li Wenliang, whose internet post about the virus provoked an official rebuke as a “rumour monger.” While reports spread widely through social media that Dr Li was a Christian proved false, the 34 year old doctor was clearly a person of sacrificial integrity and professionalism.

This pandemic, as the UN declared it to be last Wednesday, is taking on apocalyptic proportions and has us scrambling through the history books for precedents. Such a search reveals a long and intertwined history between plagues and Christian action.

Antonine Plague

Marcus Aurelius was emperor during the plague, and may have died of it.

Beyond the Biblical references – the plagues of Egypt catalysed the exodus and the eventual birth of Israel; Psalm 91 may have been written in response to a pestilence (verses 3 & 6); Revelation 6:8 predicts an outpouring of plagues – the Antonine Plague in the second century which claimed one in four Roman lives also accelerated the spread of Christianity.

Lyman Stone, writing in Foreign Policy, points out that “Christians cared for the sick and offered a spiritual model whereby plagues were not the work of angry and capricious deities but the product of a broken Creation in revolt against a loving God.”

Christians provided basic needs, food and water, for those too ill to fend for themselves, and often stayed to provide assistance while pagans fled.

Plague of Cyprian

St. Cyprian, Bishop of Carthage

A century later, the Plague of Cyprian, named after the bishop (d. 258) who urged the faithful to redouble their efforts to care for the living, resulted in marked growth of the Christian movement, according to author Rodney Stark.

Dionysius, a bishop of the 3rd century, described how Christians ‘visited the sick without thought of their own peril . . . drawing upon themselves their neighbours’ diseases and willingly taking over to their own persons the burden of the sufferings of those around them.’

The fourth-century pagan Emperor Julian (the Apostate) (d. 363) complained about those ‘Galileans’ who cared even for non-Christian sick people.

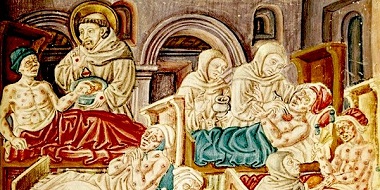

Throughout the medieval times, monks and nuns, friars and sisters, continued to put their lives at risk ministering to the sick during a plague, such as the Franciscans depicted above.

Martin Luther: ‘tempting God’

Martin Luther

Ten years after posting his 95 Theses, Martin Luther had to decide himself whether or not to flee the Bubonic Plague [Black Death; at its height in the 14th century, but persisting until the 17th century] in Wittenberg after Elector John urged him and other professors to take refuge in Jena.

His detailed answer to a pastor from Breslau asking if it was proper for a Christian to flee from a plague reveals the realities Luther and his contemporaries faced. The reformer’s response was that those with civic or religious duties should fulfill them, which by the plague become ‘crosses, on which we should be prepared to die.’

Luther also encouraged believers to obey quarantine orders, fumigate their houses and take precautions to avoid spreading the sickness. Anything less was ‘tempting God’, endangering others and ourselves, and thus transgressing the commandment against killing, including committing suicide.

Geert Grote

Geert Grote

Geert Grote (d. 1384), orphaned by the plague when he was only 10, succumbed to the plague himself after visiting a sick member of the renewal movement he started, the Brothers of the Common Life.

An audiovisual installation in the cellar of the Geert Grote Huis in Deventer, The Netherlands, a museum devoted to the story of this movement, is one of 14 artistic displays in the city depicting the stations of the cross during Lent.

Station Five – Simon of Cyrene helps Jesus carry the cross – shows three video-images projected on three different screens, filmed from a car driving through the French countryside, halting at roadside crosses. When the engine stops, the sounds of the countryside fill the cellar and invite reflection. (Sadly, the museum and exhibition have now been shut down by the restrictions.)

Carry the cross

As the world comes to standstill, an eerie silence replacing the normal hustle and bustle of daily life, we find ourselves confronted with questions of life and death, relationships and meaning, sacrifice and values, community and self-isolation.

What might it mean for us to carry the cross this Lent?

This comment is re-posted by permission from Jeff Fountain’s Weekly Word; he and his wife Romkje are the initiators of the Schuman Centre for European Studies.