In late November, the City of Vancouver released the Housing Vancouver Strategy to replace its Housing and Homelessness Strategy (2012-2021).

In late November, the City of Vancouver released the Housing Vancouver Strategy to replace its Housing and Homelessness Strategy (2012-2021).

Despite having exceeded several of the key targets it had established for this midway point in that 10-year plan, city hall desperately needed to hit the reset button. The number of homeless people is higher than ever, and the affordability crisis now impacts even the professional class.

It appears also to have impacted the future of Mayor Gregor Robertson and his Vision Vancouver party. Robertson was first elected in 2008, thanks in no small part to his promises to end street homelessness in five years.

By that measure he has utterly failed, and critics have long charged that he and his party are too beholden to the real estate industry to make substantive progress on any front of the battle for affordability. In early January he announced he will not seek re-election and several of his Vision colleagues on city council won’t either.

Good job creating housing

I’ve been a close observer of homelessness and affordable housing policy and outcomes for almost 20 years. From where I sit, Dan Fumano and Lori Culbert have offered a balanced, extensive assessment of Robertson’s performance in their January 19 Vancouver Sun article. Yes, he could and should have done more. But the primary drivers of the crisis – structured poverty, three decades of disinvestment by senior governments and foreign capital inflows – are beyond the reach of any municipality.

I’ve been a close observer of homelessness and affordable housing policy and outcomes for almost 20 years. From where I sit, Dan Fumano and Lori Culbert have offered a balanced, extensive assessment of Robertson’s performance in their January 19 Vancouver Sun article. Yes, he could and should have done more. But the primary drivers of the crisis – structured poverty, three decades of disinvestment by senior governments and foreign capital inflows – are beyond the reach of any municipality.

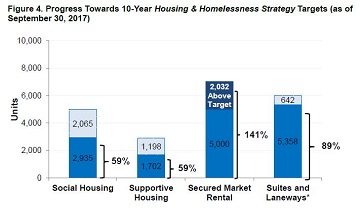

All things considered, the city has done some things remarkably well. Just 50 percent of the way through their initial 10-year plan, they’ve already reached 59 percent of their target for supportive housing, 59 percent for social housing, 89 percent for secondary and laneway suites, and 141 percent for secured market rentals (units guaranteed to remain rentals for 20-plus years).

Still, not enough

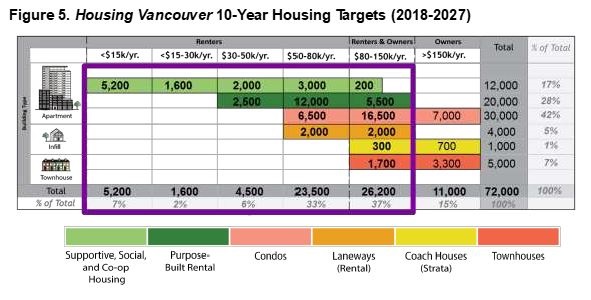

Still, that isn’t enough. The new Strategy aims to protect and improve 90,000 of the rental units that already exist, while creating over 72,000 new homes by 2027, nearly half of which will serve households earning less than $80,000 annually, and 40 percent will be family-size units.

More specifically, the city is targeting:

- 65 percent of all new housing to be for renters

- 12,000 units of new social and supportive housing (50 percent more than previous target), including 2,000 units of replacement SRO units

- 20,000 new purpose-built rental units (400 percent more than before)

- 20 percent of those new purpose-built rentals to be secured for the long term as developer-owned below-market units

- 11,000 rental units (35 percent of purpose-built, 50 percent of laneway) and 16,000 ownership units (35 percent of condos, 50 percent of coach houses) suitable for families.

The Housing Vancouver Strategy runs to 82 pages and includes eight main objectives, 33 strategies and 120 key actions. The Introduction as well as the opening sections of each chapter are very readable and give helpful context to the Strategy‘s philosophy and components. The scope of the Strategy is too much for me to comment on in detail here. So let me quote the main objectives from the Executive Summary and then point out what I think are a few of its more interesting ambitions.

Housing Vancouver Strategy: main objectives

Shift toward the Right Supply – The city must drive a significant shift toward rental, social and supportive housing, as well as greater diversity of forms in our ground-oriented housing stock. Housing and affordability must reflect the diversity of those most in need of this housing.

Shift toward the Right Supply – The city must drive a significant shift toward rental, social and supportive housing, as well as greater diversity of forms in our ground-oriented housing stock. Housing and affordability must reflect the diversity of those most in need of this housing. - Action to address speculation and support equity – We must address the impact of speculative demand on land and housing prices. We must also address calls from the public to work with partners at all levels of government to promote measures that advance equitable distribution of wealth gains from housing. This includes learning from other cities around the world that are experiencing increasing housing market pressures due to global flows of money, people and jobs.

- Protect and support diversity – We propose actions to protect and promote diversity across the city, of incomes, backgrounds, and household types.

- Protect our existing affordable housing for the future – We must preserve and expand the affordability of the existing stock of rental and non-market housing, while balancing the need to renew these buildings.

- Renew our commitment to partnerships for affordable housing – The city must commit to a new direction for affordable housing delivery, with an emphasis on supporting and aligning with partners across all sectors, particularly non-profit, co-op and Indigenous housing partners, as well as new stakeholders.

- Increase supports and protections for renters and people who are homeless – Including strategies to address affordability, security of tenure, and the determinants of poverty and housing instability.

- Align city processes with housing targets – The city must commit to aligning policies, processes and tools in order to ensure it is best positioned to enable affordable housing for all Vancouver residents.

Focus on the ‘Right Supply’

The Strategy is correct in trying to focus on the ‘Right Supply’ of unit types on every rung of the housing ladder for differing household sizes and incomes. For many years government dollars have been aimed at the very lowest rungs on the ladder to combat homelessness, in the belief that the market will take care of everyone else.

But the market has only taken care of the wealthy and those lucky enough to have bought a suitably sized home before 2005 or thereabouts. Increasing prices and rents have forced everyone else to progressively descend the ladder, so that students and the working poor are displacing pensioners and folks on welfare from the housing of last resort. That’s why the number of homeless people keeps climbing despite thousands of new supportive housing units being built.

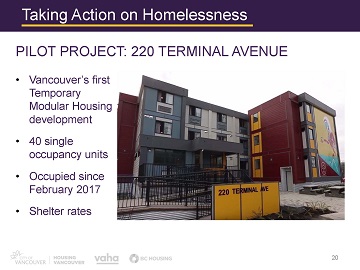

Temporary modular housing

From the Power Point presentation last November, when Mayor Gregor Robertson invited faith leaders to discuss homelessness and affordable housing.

Among the new supportive housing indicated in the Strategy, I’m elated to say, are 600 units of temporary modular housing for the homeless and other of highly vulnerable populations that the province and city have teamed up to construct and staff (with management contracts going to experienced non-profits).

The first site opens in Marpole in February and the remainder are expected by summer. The Strategy seeks a further 600 in years to come.

For a slightly higher cost per square foot, these are self-contained one-bedroom suites that can be moved from site to site on a trailer and stacked into buildings that erect within a matter of weeks.

Land is leased basically for free from the city or landowners willing to give access for five years. I remember dreaming about this very thing with Judy Graves before the 2010 Games. Additional units this year are slated for other municipalities in the region. There is more than one church that has grass or parking space better used for the kingdom in this way.

Phase out single-family zoning

For those who have eyes to see, this Strategy clearly aims to phase out single-family zoning. Good riddance to single family zoning, though not to detached houses per se. That is, to zoning that doesn’t permit any housing form other than detached houses, such as RS-1. Given our geographical constraints and projected population growth this century, Vancouver must come to look like Paris or London.

The Strategy at this point talks of opening up the low density districts to new infill formats, even experimenting with triplexes and fourplexes and collective housing. Of course, such added density does not automatically yield affordability – but it undoubtedly will create desirable options for upper middle income families who would otherwise move east to displace less well off (typically family-class immigrant) households.

Rental-only districts

More audacious is the city’s goal of getting authority as soon as possible from the province to create rental-only zoning districts. This would conceivably deflate and stabilize land values within those zones, since the more speculative dynamics of condo development would be eliminated.

I can see this working from a social planning perspective only if the rental-only zones were relatively thin within the broader mixed matrix of their neighbourhoods; otherwise the greater transience of renters could undermine efforts to forge resilient communities.

Social housing

Finally, in several places the Strategy rather vaguely talks about creating incentives and mechanisms for investment in social purpose real estate. Few Canadians know, for instance, that most of the social housing in the United States has been built by for-profit developers, because of tax incentives, inclusionary zoning requirements and community reinvestment regulations. And that’s not considering how the US and most of the Commonwealth has a far bigger toolbox than Canada when it comes to community finance (google CDFIs). Much of the latter have been pioneered by Christian groups.

It’s time we started a faith-based RRSP-eligible revolving loan fund, community land trust and/or Real Estate Investment Trust. Let’s start with the pension and development funds of denominations and religious schools. Then you and I can dedicate five percent of our retirement portfolio to it.

Thank you, Jonathan. Excellent article! The city is trying and has made some good progress, but it certainly is a moving target.

As you say, with the homeless numbers increasing and the house prices continuing to skyrocket, it isn’t enough. I appreciate the new initiatives and focus on rental units, social and supportive housing, and the move to phase out exclusive single-family zoning areas and possibly some rental only zoning. Yet, more intervention is necessary, as you note that the market has only taken care of the wealthy and those lucky enough to get into the market by around 2005.

I hope that one day the initial steps to address speculation will become much more substantial, as they have in some other parts of the world; perhaps if the broader church obtains the greater voice we desire we can speak to that more authoritatively.

Let’s talk about your dream of “a faith-based RRSP-eligible revolving loan fund, community land trust and/or Real Estate Investment Trust.”