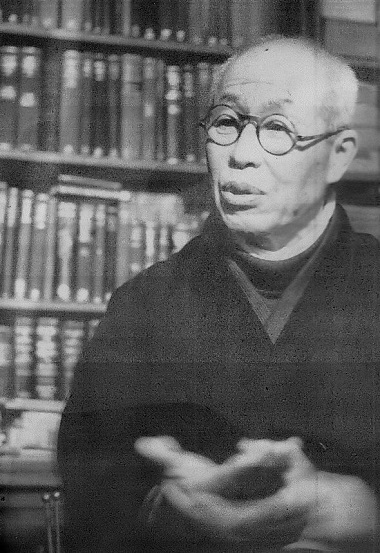

Uchiyama Kanzō was a consistent peacemaker in Shanghai from World War I right through World War II, and after. (Unknown author: Japanese magazine ‘The Mainichi Graphic, 1 April 1953 issue’ published by The Mainichi Newspapers Co., Ltd.)

Kaleidoscope: The Uchiyama Bookstore and its Sino-Japanese Visionaries tells the story of a bookstore that sold Japanese literature and fostered surprising friendships in Shanghai between 1917 – 1945.

Such a topic might seem quite distant and esoteric from the vantage point of the Christian community in Vancouver almost a century later

However, apart from the fact that Kaleidoscope (Earnshaw Books, 2022) offers a unique perspective on a fascinating time – Japan had taken over large parts of China, including Shanghai, and the Communist Party was on its way to power – there are also some interesting local connections.

Naoko Kato

The first of those connections is that the author lives in Vancouver. Naoko Kato teaches East Asian history at St. Mark’s College, an affiliate of UBC.

She presented her work at at book talk/launch at the UBC Asian Centre as part of the Japan Lecture Series, April 12.

Addressing the issue of why she wanted to write the book, Kato said, “I wanted the book to be able to able to be read as both Chinese and Japanese history.” Noting that during the time period covered by the book, the nations were either at war or had no diplomatic relationships, she added, “I wanted to humanize the other, the ex-other rather.”

More on local connections toward the end.

Synopsis

The invitation to the book launch included this synopsis of Kaleidoscope:

The invitation to the book launch included this synopsis of Kaleidoscope:

In the 1920s, a Japanese businessman set up a bookshop in the city of Shanghai which changed the course of history by providing a forum for Chinese and Japanese intellectuals to meet and discuss the great issues of the day.

Now, Naoko Kato’s powerful book Kaleidoscope looks at the story of Uchiyama Kanzō and his bookstore from a fresh perspective, breaking it down into a series of reflections that shift as the years turn.

Uchiyama’s bookstore was a fulcrum of Sino-Japanese contacts; many of the members of Uchiyama’s salon were intellectuals behind the Chinese Communist Party, then an illegal organization in Shanghai.

The ability of Uchiyama and his bookstore to transcend intellectual divisions and borders makes his story of unique inter-cultural interest. And the context of Uchiyama’s efforts to bring peace between his home country of Japan and his chosen home of China is one of the most intellectually uplifting stories of the 20th century.

Spiritually uplifting as well.

Christian roots

Thus far, one might not have realized that the main character of Kaleidoscope was a Christian, if an unusual one. Uchiyama Kanzō and his wife Miki opened the bookstore as a way to distribute Japanese language Christian materials.

Kato noted during her presentation that Miki’s gravestone, side-by-side with Kanzō’s states that she was the founder of the store. He was a successful businessman, working for an Osaka-based pharmaceutical company.

In today’s terms, one might consider him a unique combination of a ‘business as mission’ entrepreneur / missional thinker / peacemaker / social justice warrior. But of course he lived in an entirely different time, and creatively charted his own path.

When I asked whether Uchiyama might properly be considered a missionary, Kato said that while he was a committed Christian, someone who supported Christian humanism, he would not necessarily be thought of as a missionary. (I still like to think he was a model missionary, though not, admittedly, a conventional one.)

Naoko Kato presented her work at at book talk/launch at the UBC Asian Centre.

Kato described his faith in Kaleidoscope:

Uchiyama Kanzō was not a stereotypical Japanese conformist. He was a social activist with a robust sense of personal identity. He was a Christian who lived his faith despite constant accusations by Japanese of being unpatriotic and spying for the Chinese.

He was not content to exercise his faith by merely attending church services. His mission was to make a visible difference in the world.

To this end, under the growing influence of nationalism, hostility between Chinese and Japanese people, and war between two nations, Uchiyama devoted his life to facilitating connections between individual Chinese and Japanese people and ultimately to the furtherance of cross-cultural understanding between the peoples of the two nations.

Most significantly, Uchiyama Kanzō humanized the enemy – an activity that took exceptional faith and courage.

Kato also noted that Uchiyama not only differed from most fellow Japanese citizens:

. . . [He] even deviated from well-known Japanese Protestant Christians. With their educational credentials and samurai family backgrounds, these elite Japanese primarily viewed Protestant Christianity as part of Japan’s path to modernization and salvation of the country from the fate of other East Asian countries in the face of Western military might.

In contrast, Uchiyama was a ‘born again’ Christian. His conversion to Christianity resembled the story of the Prodigal Son, who wasted his life and then returned home and received his father’s forgiveness.

While Uchiyama was a visionary, willing to strike out on his own, he did continue to interact with like-minded Christian thinkers in Japan.

A cultural salon

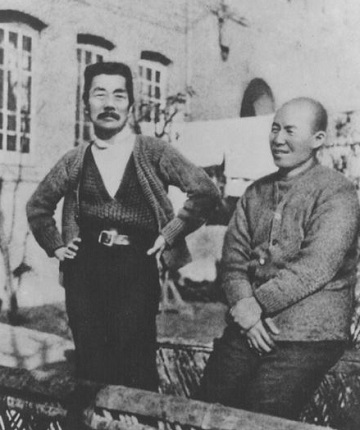

Lu Xun and Uchiyama Kanzō were constant companions at the bookstore. Photo: Photo: Uchiyama Books Co.

The bookstore began as a Christian enterprise, but soon broadened out, selling a wide range of books and operating as a cultural salon.

Kato wrote:

Between World War I and World War II, Uchiyama Bookstore would evolve into one of Shanghai’s most famous bookstores and a magnet for Chinese and Japanese literati.

Although it continued to carry Christian-related titles, it was not a Christian bookstore during most of its 30 years of operation. With its foundation in Uchiyama Kanzō’s and Miki’s Christian faith, the spirit of the bookstore was Christian to its core.

The name of the book describes the various networks around Uchiyama Bookstore. Kato uses “eight turns” of the kaleidoscope to introduce the ever-changing case of characters.

The chapter headings are:

- A Christian Bookstore (1875 – 1917)

- Pan-Asian Dreams (1878 – 1913)

- A Sino-Japanese Bookstore (1917 – 1924)

- A Sino-Japanese Cultural Salon (1926 – 1930)

- A Haven (1927 – 1936)

- Searching for Peace Amidst War (1925 – 1945)

- Japan-China Friendship Association (1945 – 1959)

- Epilogue

The best known figure during the bookstore’s time as a cultural salon was Lu Xun. Writing about a related book – A Friend in Deed: Lu Xun, Uchiyama Kanzō and the Intellectual World of Shanghai on the Eve of War by Joshua A. Fogel (Fogel was on the zoom call for Kato’s talk) – John Darwin Van Fleet described the unlikely success of the bookstore.

He added:

And if that’s not improbable enough, now imagine that the bookshop becomes a magnet for the leading literary figures of both China and Japan within 10 years of its founding – another author, Paul French calls the Uchiyama Bookstore “ground zero for Asian literary modernism.”

And that the towering literary figure of early 20th century China, Lu Xun, would first visit in 1927, and subsequently make the bookstore not only his professional base of operations and his sole publisher, but also hide there from the murderous clutches of China’s ruling Guomindang, and become the best friend and daily interlocutor of the bookstore’s Japanese co-founder, until Lu’s death in 1936.

Kato said during her talk that she wanted to focus not only on Lu Xun, and she succeeds. The parade of intellectuals, leftist writers, labour leaders, students and communist activists (both Chinese and Japanese) can be a bit bewildering, though the book is not a difficult read.

Post-war influence

The Uchiyama Bookstore opened its doors to welcome readers in Shanghai last fall. Photo: China Plus Culture Facebook

Following his wife’s death, and the war, Uchiyama carried on with his peace-making endeavours:

Though forced to leave China in 1947, Uchiyama remained true to his vow. He redoubled his efforts and focused on bridge-building between Japan and China in the opposite direction.

He and a ‘Shanghai Group’ established the Japan-China Friendship Association in 1950.

“From its beginning,” Kato wrote, “JCFA was undeterred by anti-communist pressure and called on the Japanese government to prioritize the normalization of diplomatic relations with the PRC.”

Though Sino-Japanese relations are currently not particularly warm, Uchiyama would no doubt be glad to know of Uchiyama Bookstore’s revival in China.

A November 30, 2022 post on China Plus Culture (described on Facebook as a “China state-controlled media”) stated:

The Uchiyama Bookstore opened its doors to welcome readers in Shanghai this week. The renovated store was built in 1917 by Japanese Uchiyama Kanzō. Lu Xun, a well-known Chinese writer of the early 20th century, was a regular visitor at the bookstore back then. Lu and Uchiyama built their friendship at the store, which became a popular meeting place for intellectuals and students at the time.

A February 14 post on the Tokyo-based Kyodo News (‘Historic Japanese bookstore’s revival in China boosts cultural ties’) begins:

A February 14 post on the Tokyo-based Kyodo News (‘Historic Japanese bookstore’s revival in China boosts cultural ties’) begins:

A Japanese bookstore that was frequented by famous Chinese authors such as Lu Xun and Guo Moruo in early 20th-century Shanghai is once more thriving as a center of cultural exchange after being reborn in Tianjin, a port city southeast of Beijing.

The original Uchiyama Shoten bookstore, founded in 1917 by Kanzō Uchiyama (1885-1959), was known as a salon for Chinese intellectuals and a space where they could also interact with visiting Japanese, even when the two countries edged toward war in the 1930s.

Now two bookshops, opened in 2021 and last year by a Chinese company, bear the Uchiyama Shoten name with the blessing of Uchiyama’s descendants and are recreating the old salon atmosphere by becoming spaces for both conversation and Sino-Japanese cultural encounters.

The manager hopes to open similar bookstores in other parts of China.

Local connections

Among Uchiyama Kanzō’s many friends and acquaintances were some prominent Japanese Christians, three of whom have some connection with Metro Vancouver: Nitobe Inazō, Kagawa Toyohiko and Uchimura Kanzō.

Kato wrote that Uchiyama was invited to lunch with a group of prominent Japanese Christians, including peace activist Nitobe Inazō, in 1932:

A special edition of the newspaper had just announced the Japanese Army’s occupation of Jinzhou (in Manchuria). Nitobe was sitting off to the side reading the newspaper. Uchiyama heard him mumble to himself, “In the end, the army will lead Japan into defeat.”

These men were spokesmen to the international community on behalf of others in Japan who shared their views.

Nitobe Memorial Garden celebrates the memory of Dr. Inazō Nitobe.

Nitobe and Kagawa Toyohiko founded the Fellowship of Reconciliation and the League of Nations Association of Japan. Uchiyama had invited Kagawa to speak in Shanghai years earlier.

Nitobe Inazō is known in Vancouver because of the Nitobe Memorial Garden, which sits right beside the UBC Asian Centre.

The garden’s website includes these words:

Nitobe Memorial Garden celebrates the memory of Dr. Inazō Nitobe (1862-1933), a remarkable Japanese figure whose goal was “to become a bridge across the Pacific.”

Throughout his life, Dr. Nitobe strove to promote a better understanding of Japanese culture in the West at a time when Japan was inconceivably foreign in the minds of most Westerners.

Unfortunately, he died on October 15th 1933, in Victoria, British Columbia, en route to Japan following a conference of the Institute of Pacific Relations in Banff, Alberta.

Kagawa spoke to large crowds all over North America. Described in glowing terms by The Vancouver Sun as an evangelist and social worker “after 15 years of slum work,” he was welcomed by Vancouver’s General Ministerial Association to speak at Wesley Church July 22, 1931.

United Church archives note that “Yoshinosuke Yoshioka was born in Sasebo, Japan in 1889. Mr. Yoshioka’s conversion to Christianity was influenced by the Rev. Toyohiko Kagawa of Kobe.” Yoshioka ministered at Japanese Methodist Church in Steveston and the Japanese Mission on Powell Street in Vancouver during his career.

Uchimura Kanzō was an author, evangelist, scholar and founder of the Nonchurch Movement (Mukyōkai) of Christianity. I am not sure that he ever visited Vancouver, but – the late John F. Howes, one of UBC’s best known Asian scholars (and a member of Christ Church Cathedral), wrote his biography: Japan’s Modern Prophet: Uchimura Kanzō, 1861 – 1930 (UBC Press, 2006).

The pastor of Uchiyama’s church in Kyoto encouraged him in 1913 to go to China to work. When Uchiyama agreed, he “exchanged his possessions for a Bible, a hymnal and copies of Uchimura Kanzō’s monthly magazine Biblical Studies (Seisho no kenkyū).”