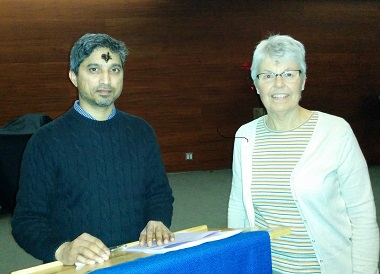

Pastor Sandeep Jadhav has introduced the observation of Ash Wednesday to New Life Community Church in Burnaby. With him is New Life member Gillian Coates.

Breaking bread and drinking wine with his disciples just before his arrest, Jesus said, “Do this in remembrance of me.” He commanded them (and us) to partake in the embodied act of eating and drinking as a way of fellowship with him and each other.

We also utilize our bodies in worship by singing, reciting litanies and creeds, lifting hands of praise. But the earthy practices of former centuries have been largely lost to us.

A common practice for Ash Wednesday was to smudge ashes on believers’ foreheads in the sign of the cross, still observed in Catholic and some Protestant traditions. This beautiful custom was a reminder of their human condition – sinful, and in need of Christ’s grace and mercy. In the reformers’ zeal to purge the church of false theology and misguided ritual, some meaningful spiritual practices were abandoned – practices that the Protestant church has begun to carefully negotiate in recent years.

Liturgical rhythms

The church calendar includes a rhythm of fasting and feasting. The season of Advent allows Christians a more solemn time of waiting for the coming of Christ – a focus that allows us to sidestep, to a degree, the commercialization of secular ‘holiday’ preparations. On Christmas day, our waiting over, we celebrate His birth with joyful carols, lavish tables, gift giving and good will towards all.

Similar to Advent, Lent provides us a period of concerted reflection on Christ’s suffering – his groaning under the weight of our sin. Shadows of self-examination and dwelling on our suffering Saviour culminate in the brilliant light of resurrection glory. Unless we experience the contrast of our darkness and Christ’s light, we miss the most profound joy.

Rediscovering lost disciplines

Dr. Bruce Hindmarsh, Professor of Spiritual Theology at Regent College, explains that since the 1970s, Protestants have been more widely read, discovering resources and seeking to incorporate practices to enrich their faith walk. [See accompanying article about the launch of his new book, The Spirit of Early Evangelicalism.]

Hindmarsh sees two streams of disciplines – some are for intensifying, and some for clarifying our relationship with God. The window is often smudged – clouded with distractions of our own choosing.

“I desperately want to see the face of my Beloved on the other side of this window. With what discipline . . . what alacrity . . . what energy will I engage to clear the window,” he asks, “so that I can see the face that I most love in all the world?”

Fasting, and other disciplines

Fasting is a word synonymous with Lent. Hindmarsh states that Lent provides occasion to “check yourself; are there things that have become addictive – things that are getting in the way of seeing Jesus more clearly?”

Our appetites for food, drink, technology, entertainment or a host of other distractions often take up too much space in our lives. We are freed to say “no” to our personal addictions and replace them with a “yes” towards something better that will intensify our encounter with God.

Can we replace the time we spend on social media, for instance, with slow reading of a Lent devotional, spiritual book or book of the Bible? Hindmarsh adds that when we give up something, we recognize that our distraction may be a good gift from God, but it is not ultimate. Rather, our love for God holds preeminence.

Slow reading, a Benedictine practice of digesting a devotional or book of the Bible carefully – not theologically as we would for a Bible study – is meant to deepen our own encounter with the word of God.

“If you think of that as being like a magnifying glass that intensifies my gaze at the beloved – the lover wants to linger over every detail of the beloved – and prolong my encounter with the beloved,” says Hindmarsh.

Some churches take Lent as an opportunity to read a specific book or devotional together over the 40 days of Lent. [February 14 – April 1]

Retreating to a quiet place helps us realize how cluttered our lives have become. In the silence, we realize how noisy our environment and even our own minds often are. In a quiet space away, we can reset our spiritual compass. Walking, noticing creation around us, becoming still – all give occasion to enter into closer, deeper relationship with our Father, Saviour and Comforter. We can also feel free to express our personal worship in intimate ways we might not practice when we are around others. Fasting can be incorporated into a retreat, as can slow reading and meditating – perhaps on a short passage, or even a single word.

Stations of the cross set up around a church building, or even at home is a reminder of Jesus’ life and death – his humanness and identification with us. Stopping at each station to reflect on Christ’s journey can be a profound experience of deeper connection with him. This experience can be likened to a spiritual pilgrimage of sorts – perhaps taking a number of days to reflect on one station before moving on to the next.

The things of Christ

Rather than a “no,” Lent becomes a resounding “yes” to the things of Christ. Hindmarsh is adamant in stating the importance of observing Lent practices not as a way to be more disciplined or to feel better about ourselves, but for the sake of love. We examine our lives. We repent. We develop new habits for our continuing journey, learning better to serve others in love.

On Easter, after this “season of seriousness,” Hindmarsh concludes, “it is such a joy to gather round the table and have a special meal, open a special bottle of wine, and welcome with great joy the feast of the resurrection.”

This article first appeared in the February issue of The Light magazine and is re-posted by permission.