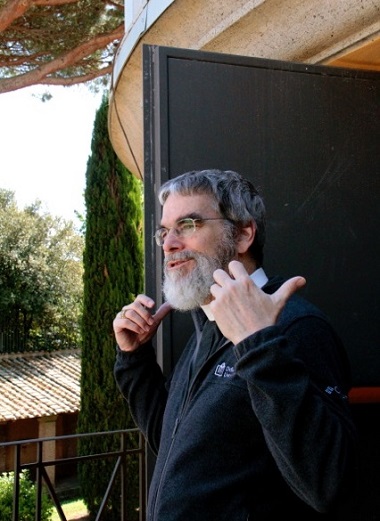

As Brother Guy Consolmagno showed Colleen Barlow around Castel Gandolfo, he said, “We are doing this science for God.”

Brother Guy Consolmagno, SJ will speak on the topic Why Do We Look Up at the Heavens? November 22. The event is presented by St. Mark’s College in partnership with UBC’s Department of Physics and Astronomy.

Vancouver artist Colleen McLaughlin Barlow was given a tour of the Vatican’s centre for astronomy by Consolmagno this spring. Here she describes how that came about.

The Vatican Observatory has a massive public relations challenge. When most people, even well educated people, hear ‘Vatican’ and ‘science’ in the same sentence, they immediately think of Galileo, and shake their heads disparagingly about the backwardness of the Church.

Some time after the Galileo trial, a new Pope directed all scientists to seek out the truth of the universe in an effort to better understand the glory of God’s creation. So, for almost 400 years, the Vatican has produced much of the solid science underlying current astronomy.

Art residencies / international telescopes

I am a visual artist living in Vancouver, writing a book about my art residencies at international telescopes over the past five years (‘Making Art at 14,000 Feet’). I would not have sought out Vatican astronomy except for a wrinkle in accommodation plans.

The director of the world’s largest telescope, the Large Binocular Telescope on Mount Graham in Arizona was commissioning the world’s first ground-based space laser, which acts as a guide star for the telescope’s amazing dynamic optics systems. There were scientists and engineers from many countries staying up at the telescope for this event. I was also on hand to photograph the night’s activities but they suddenly noticed that there were no beds left in the dormitory.

The ever-resourceful director, Dr. Christian Veillet, asked if I could stay overnight at the telescope just down the road – the Vatican Advanced Technology Telescope. The administration at the VATT very kindly offered me a bed and so I was scheduled to ‘sleep with the Jesuits’ for the following week.

While staying there, I met the brilliant and delightful Father Christopher Corbally, a Jesuit of significant scientific achievements (on the committee responsible for downgrading Pluto from planet status) who gave me an extensive tour of the VATT as well as telling me a bit about historic Vatican astronomy. I was intrigued, and on his suggestion applied to the official press office at the Vatican to see some of the historic astronomy collection in Italy and meet the man heading up Vatican astronomy.

Brother Consolmagno / Vatican Observatory

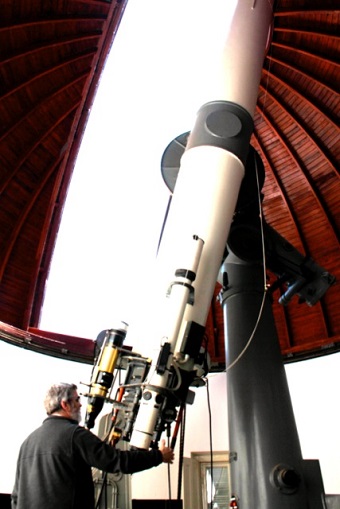

Historic telescopes at which WWII refugees were housed during the war at Castel Gandolfo.

I met Brother Guy Consolmagno this spring at his headquarters at Castel Gandolfo, the Pope’s summer palace, about a half hour south of Rome.

He is a charming American, from Detroit originally, and is one of the world’s top meteorite scientists. He has taught at Harvard and MIT and served in the Peace Corps in Kenya for a few years. He took vows to be a Jesuit brother in 1991. In addition to astronomy, Brother Guy has also studied theology and philosophy. He continues in his research work in astronomy and is the current director of the Vatican Observatory.

In 1996 he participated in the Antarctic Search for Meteorites where he discovered a number of meteorites. The International Astronomical Union named an asteroid (4597 Consolmagno) to honour him.

He is a brilliant speaker and has received a number of awards for science communications, including the American Astronomical Society’s Carl Sagan Medal for communication to the general public by an active planetary scientist. He is passionate about proclaiming the need for good science and that science and religion must work alongside each other rather than as competing ideologies.

Seeing the history of astronomy

Brother Guy Consolmagno sets up the solar telescope for viewing.

On the morning of my visit it was sunny in Rome and the half hour train trip out to Castel Gandolfo took us through rolling hills and small farms. My husband Martin and I arrived to be met by Brother Guy and some of his staff.

After a perfect espresso coffee made by Brother Guy’s colleague we moved through the impressive historical collections including a guest book with scientific signatures by the likes of Ernest Rutherford and Niels Bohr, books about astronomy dating back to before 1600 and lovely daguerreotypes of the Italian nuns who made computations before computers were available to help map parts of the universe in the 1800s.

There are historical telescopes, lenses and a terrific collection of meteorites. After leaving the main building, we saw the monumental telescopes of the past, lined with rich woods. I took many reference photographs for future art projects about this material.

A unique calling

During my art residencies, I interviewed astronomers and astro-physicists from a number of countries and asked them about the Vatican astronomers. The comments were all very positive. It was pointed out that because the Vatican scientists did not need to apply for grant money every three years, they can do the type of long-range work that would be very hard for a secular scientist at any university to do.

As well, several astronomers pointed out that because they do not have families or any other secular distractions, Vatican scientists’ dedication to the work is impressive.

Brother Guy agreed and spoke about the dedication and passion of Vatican astronomers being rooted in faith: “We are doing this science for God.”

Colleen McLaughlin Barlow on a hoist to have a closer look at the main reflective lens at the Large Binocular Telescope in Arizona.

Colleen McLaughlin Barlow is a visual artist living in Vancouver. For the past five years she has been busy at artist residencies at different international telescopes. She has worked at the Canada France Hawaii Telescope in Hawaii, the Gemini Telescope in Chile, the Large Binocular Telescope in Arizona and the Vatican Advanced Technology Telescope on Mount Graham, as well as the centre for Vatican Astronomy at Castel Gandolfo in Italy.

She is currently writing a book about her adventures called ‘Making Art at 14,000 Feet.’ She spoke about the project September 10 as part of the Learners’ Exchange series at her church, St. John’s Vancouver.

Note (November 22): There have been a couple of good interviews in the secular media, in The Vancouver Sun and on CBC’s Early Edition (go to 2:40:51).