There is an ocean width of difference between being alone and being lonely. Some think it is language, unaffordable housing, technology or erratic work schedules that distance us from each other. For newcomers to Canada, it may be all of these and more.

Annie Meng

Annie Meng grew up as a Buddhist in China. She, her husband and daughter immigrated to Canada, first in Edmonton, as skilled workers, but she soon realized she had no community or family support in this new city.

Depression consumed her, she lost her job, and conflict escalated in her marriage. One senior woman stepped into her world, listened to her and gave her hope to try another day. She was welcomed into a church community.

When her daughter was accepted into UBC, Meng transitioned to Vancouver. The pastors who knew her from her first experience in Edmonton recommended a church in Vancouver. She had arrived in Canada with her small family but with no furniture, no extra clothes, no cooking pots and no clue how to integrate into her strange new world.

In both cities the church she approached met her basic needs and welcomed her. She learned to smile again.

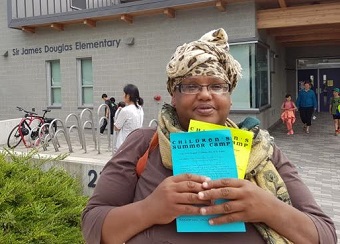

Halima Yousef

Halima Yousef, who came to Canada from East Africa, is still alive because of community. “I almost committed suicide many times,” she says. “I even drank bleach to try to end my life. I wanted to kill myself and my kids. Alcohol became my best friend. I drank to cover up my pain. Someone called the police and they saved me from myself.”

Yousef says newcomers to Canada need community to overcome loneliness because they face challenges in “language, education, isolation, feeling welcomed, homesickness and friendship . . . I am over 40 and only now learning to read and write.”

She feels deeply for incoming Syrians and Iraqis. Her life of isolation started early, while still in a refugee camp – raped by her uncle when she was eight, thrown out to live on the streets when she was 11, married to an abusive Canadian drifter when she was 15, brought to Canada and sequestered behind closed doors.

Eventually divorced and left to raise three children on her own, she embraced “bad company” and drifted into life-destroying relationships and habits. Her mental health plummeted as she fixated on the torturous abuse of her childhood and marriage.

Engaging with church

Yousef’s first taste of happiness occurred as if by chance. In desperation she went to a food bank. She met a pastor who was wearing a beaded wristband she recognized from her home country. He was Caucasian but he was the first person who showed her respect, gentleness and genuine care. He invited her into community, found others to come alongside her. She slowly began to engage.

Engaging with a church was a challenge. She’d grown up in Islam and felt the sting of abuse and threats. Among followers of Jesus, she learned she was important and part of a family.

“When you are sick and lonely, you need to hear this. I have no regrets. When my First Nation’s neighbour asked me why I am so happy now, I tell her it is because I have Jesus in my heart and I got baptized to follow him. She comes with me and now she is happier. Last week she brought another friend.”

Reaching out to others

Meng was recently baptized and proclaimed her faith to six colleagues she brought with her as witnesses.

“I’ve actually found more joy than happiness,” says Meng. “My husband went back to China to care for his parents and my daughter went to Toronto. I need the community of Jesus more than ever. It is hard to be alone here.”

Meng also has found hope in visiting and reaching out to others who are struggling in the city.

“I found I am still able to do something worthwhile. When I listen to the stories of others and pray for them, I realize I am not the only one who is experiencing these hard things. I am not the worst.”

Feeling genuine love

Yousef explains the changes in her life during the past few months are because of the encouragement of her new community.

“I learned to read and write and to use a bank machine. I am now calmer, I quit drinking, I am off medication, I pray to Jesus all the time, I forgive all those who hurt me, I try to make friends with lonely people, I tell my children I love them, I reach out to my neighbours and I invite everyone to come with me to the church. It is a community for healing, hope and help.”

The need to belong is a universal thirst across ethnic, gender, age and social boundaries. When people are lonely they trust others less; they feel less connected to their community; they limit participation in healthy interaction; health conditions deteriorate. When community is working and happiness is increased those trends will be reversed.

Meng says: “I have moved from looking at myself to seeing the wider community. . . . I belong to a Bible study, get involved in volunteer opportunities and go on visitation. Outside the church I was rejected. Inside I was accepted. I felt a genuine love, especially from the senior believers.”

Find a good church

For both Yousef and Meng, it was one person who reached out and drew them into community where they were accepted, affirmed, supported, listened to, encouraged and helped with practical needs.

Both these women have seen what the prayers of others meant for them and now they are passing on their prayers for others who desperately need the community of Jesus.

Yousef says: “I just hope my story can help someone. Tell them to find a good church.”

This article is re-posted by permission from The Light Magazine.