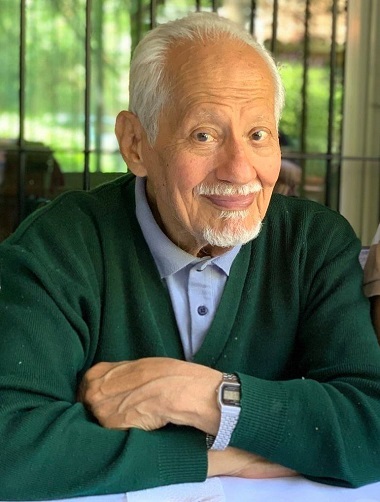

René Padilla, 1932 – 2021; photo by Ruth Padilla DeBorst.

Leaders from around the world have offered tributes since Ecuadorian theologian/pastor René Padilla died last week.

Miroslav Volf (founder and director of the Yale Center for Faith & Culture), for example, said, “René Padilla was one of the heroes of modern church history. He has been a blessing to the nations: to the church globally and the world more broadly.”

Christianity Today posted these comments in their obituary:

Padilla was best known as the father of integral mission, a theological framework that has been adopted by over 500 Christian missions and relief organizations, including Compassion International and World Vision.

Integral mission pushed evangelicals around the world to widen their Christian mission, arguing that social action and evangelism were essential and indivisible components – in Padilla’s words, “two wings of a plane.”

Padilla’s influence surfaced most prominently at the Lausanne Congress of 1974, where he gave a rousing plenary speech. Nearly 2,500 Protestant evangelical leaders from over 150 countries and 135 denominations gathered in Lausanne, Switzerland, at a meeting funded primarily by the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA).

One influential magazine [Time] called Lausanne “a formidable forum, possibly the widest-ranging meeting of Christians ever held.” When Padilla ascended the stage, he carried the hopes and dreams of many evangelicals from the Global South who sought equal footing in the decision-making of worldwide churches and mission organizations.

Padilla specifically called American evangelicals to repent for exporting the “American way of life” to mission fields around the world, devoid of social responsibility and care for the poor, making the case for misión integral.

Go here for the full CT comment, which refers to some of the ‘evangelical credentials’ which helped buttress Padilla’s credibility in challenging American hegemony.

Growing up, he and his family were stoned and their homes firebombed as they planted churches in staunchly Roman Catholic Colombia. He ministered with American missionaries Jim Eliot and Nate Saint before before they were killed by the Waorani people they were trying to reach (thus becoming unofficial evangelical saints). He translated for Billy Graham Crusades across Latin America.

The Lausanne Movement has posted ‘The late René Padilla and the Speech that Shook the World,’ saying:

The 1974 Lausanne Congress was the first time leaders from the Global South were given a place among the world’s evangelical leadership. So when Latin American theologian René Padilla ascended the podium to give his address, he carried the hopes of the Global South with him.

In honour of René’s passing on 27 April 2021, we bring to you the seminal address that set the 1974 Congress alight. His message rebuking worldly culture Christianity and challenging the global church to move instead toward humility, theological renewal and cross-fertilization remains timeless and especially prescient for us today.

Following are some excerpts from Padilla’s address:

Evangelism and the World

Please allow me to clarify that I have no intention of judging the motives of the propounders of American culture Christianity. It is the Lord who judges; when he comes he will disclose the purposes of the heart and ‘if any one builds on the foundation with gold, silver, precious stones, wood, hay, straw – each man’s work will become manifest; for the day will disclose it’ (1 Cor 3:12-13).

My duty before God this morning is rather to try to make, with as much objectivity and fairness as I can, a theological evaluation of a type of Christianity which, having as its center the United States, has however spread widely throughout the world.

René Padilla addressing the 1974 Lausanne Congress

Granted, I could have chosen a variety of ‘culture Christianity’ other than ‘the American Way of Life’, as some of you have suggested.

l do not wish to imply that American Christians are the only ones who may fall into the trap of confusing Scripture and culture. The fact, however, is that, because of the role that the United States has had to play in world affairs as well as in the spread of the Gospel, this particular form of Christianity, as no other today, has a powerful influence far beyond the borders of that nation. So, for those of you who wonder why I condemn the identification of Christianity with ‘the American Way of Life’ but not with other national cultures, this is my answer.

Behind my condemnation of this variety of culture Christianity lies a principle to any other kind of culture Christianity, namely, that the church must be delivered from anything and everything in its culture that would prevent it from being faithful to the Lord in the fulfilment of its mission within and beyond its own culture.

The big question that we Christians always have to ask ourselves with regard to our culture is, ‘Which elements of it should be retained and utilized and which ones should go for the sake of the Gospel’?

When the church lets itself be squeezed into the mold of the world, it loses the capacity to see and, even more, to denounce, the social evils in its own situation. Like the colorblind person who is able to distinguish certain colors but not others, the worldly church recognizes the personal vices traditionally condemned within its ranks, but is unable to see the evil features of its surrounding culture.

In my understanding, this is the only way one can explain, for example, how it is possible for American culture Christianity to integrate racial and class segregation into its strategy for world evangelization.

The idea is that people like to be with those of their own race and class and we must therefore plant segregated churches, which will undoubtedly grow faster. We are told that race prejudice ‘can be understood and should be made an aid to Christianisation.’

No amount of exegetical manoeuvring can ever bring this approach in line with the explicit teaching of the New Testament regarding the unity of men in the body of Christ:

‘Here there cannot be Greek and Jews, circumcised and uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave, free man, but Christ is all, and in all’ (Col 3:11); ‘There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus’ (Gal 3:28).

How can a church that, for the sake of numerical expansion, deliberately opts for segregation, speak to a divided world? By what authority can it preach man’s reconciliation with God through the death of Christ, which is one aspect of the Gospel, when in fact it has denied man’s reconciliation with man through the same death, which is another aspect of the Gospel (Eph 21:14·18)?

As Dr Samuel Moffett put it at the Berlin Congress, ‘When racial discrimination enters the churches, it is something more than a crime against humanity; it is an act of defiance against God himself.’ . . .

The third section of my paper deals with evangelization and involvement with the world. Here I first propose that repentance, conceived as a reorientation of one’s whole personality, throws into relief the social dimension of the Gospel, for it involves a turning from sin to God, not only in the individual subjective consciousness, but in the world. Without ethics, I say, there is no repentance.

Am I slighting the personal aspect of evangelization, as I have been accused of doing? I don’t think I am. What I am doing is recognizing that man is a social being and that, therefore, there is no possibility for him to be converted to Christ and to grow as a Christian except as a social being. Man never turns to God as a sinner in the abstract – he always turns to God in a specific social situation. . . .

Under the subtitle ‘evangelism and other-worldliness’ I speak of two extreme positions with regard to the present world.

The one is that which conceives of salvation as something that fits within the limits of the present age, in terms of social, economic and political liberation. The personal dimensions of salvation are eliminated or minimized. The individual is lost in society.

There is little or no place for forgiveness from guilt and sin, or for the resurrection of the body and immortality. This world is all that there is and the fundamental mission of the church must therefore be conceived in terms of the transformation of this world through politics.

At the other end of the scale is the view according to which salvation is reduced to the future salvation of the soul and the present world is nothing more than a preparatory stage for life in the hereafter. The social dimensions of salvation are completely or almost completely disregarded and the church becomes a redeemed ghetto charged with the mission of rescuing souls from the present evil world.

Didn’t Jesus say, ‘My kingdom is not of this world’? Why should the church be concerned for the poor and the needy? Didn’t he say, ‘The poor you always have with you’? The only responsibility that the church has toward the world is, then, the preaching of the Gospel and the planting of churches. ‘There are many goods the church may do, of course; but they do not belong to its essential mission.’

I maintain that both of these views are incomplete gospels and that the greatest need of the church today is the recovery of the full Gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ – the whole Gospel for the whole man for the whole world.

Go here for René Padilla’s full speech at Lausanne in 1974.

Lasting impact?

There is no doubt that Padilla is widely admired, though some wonder about his legacy. David Swartz, author of Facing West: American Evangelicals in an Age of World Christianity (Oxford University Press, 2019) wrote a colourful description of opposition to Padilla both during and after the 1974 Lausanne Congress.

There is no doubt that Padilla is widely admired, though some wonder about his legacy. David Swartz, author of Facing West: American Evangelicals in an Age of World Christianity (Oxford University Press, 2019) wrote a colourful description of opposition to Padilla both during and after the 1974 Lausanne Congress.

He concluded:

Which is what makes Christianity Today’s obituary of Padilla last week so remarkable. In the end, Padilla clearly won over the evangelical cosmopolitans. Some of the highest praise of Padilla after his death came from Christianity Today, Fuller Theological Seminary and a long list of Never-Trumpers.

Of course, that’s a somewhat hollow victory for advocates of Integral Mission now, given Christianity Today’s own marginalized position in the post-2016 evangelical landscape.

Swartz is referring primarily to responses in the United States, but the broader picture looks more hopeful for Padilla’s legacy.

Here is an excerpt from the World Evangelical Alliance (WEA) tribute:

Thomas Schirrmacher teaching at the WEA General Assembly in November 2019.

WEA Secretary General Thomas Schirrmacher recalled his interaction with Padilla at the Lausanne Movement’s Cape Town conference in 2010:

For me, it felt as if I was talking to the church fathers! René shaped the thinking of many in my generation.

At a time when evangelicalism was still dominated by rich Western countries, he paved the way for the church in poorer countries – a church often discriminated against and suppressed yet not falling into a victim mindset, but rather wanting to transform the world for Jesus.

René taught us that the church does not exist to fit nicely into a rich world, but always keeps an element of a counterculture. He helped us to understand that the evil patterns present in this world are not just individual, private sins and shortcomings but include structural injustices as well.

And most importantly, he not only formulated an ambitious agenda regarding whether we are really living up to God’s will as described in Scripture, but he lived it out himself. We thank René for willingly taking the heat over decades of discussions, and we thank the Holy Spirit for planting René’s vision into the heart of many.

Go here for the full WEA tribute to René Padilla.

Thanks , Flyn, for refreshing us with Padilla’s address. I am deeply thankful to God for his work, whom I first read about in Let the Earth Hear His Voice some three decades ago, and whose profound visionary message has helped much of my path afterwards.

For those unconvinced about René’s proposed Integral Mission or his condemnation of “culture Christianity,” I’d like to share what an Indigenous Christian leader brought up at a unique Native Chinese Leadership Consultation in Edmonton in 2005.

He calmly told those attending that he knew of 50 Indigenous Christians, who had not only completed biblical and theological studies, but had dedicated themselves to become missionaries. However the sad ending is that none of them was able to become one since they were not accepted by major Canadian missionary organizations.

As Canadian churches are not immune to similar integration of racial segregation, may the Spirit awaken us to the Gospel’s demand for radical reorientation of life, and in memory of René, to love is to do justice.

Hi Flyn,

Thanks for publishing this article about Rene Padilla. His thinking and leadership influenced the whole of Latin America. In my years in in the Dominican Republic he, together with a handful of other Latin American evangelical leaders, gave us greatly appreciated guidance and direction in outreach.

While admirable that Rene Padilla challenged “american” Xianity and its import over generations (now centuries?), is it fair to state that any version of the gospel, biblically based or rooted included, can be free from its own cultural means of communication and all that that includes, even if subconscious or implicit or tacit or subterranean?

Biblical scholarship – and not only liberal, neo-orthodox, conservative and/or evangelical – is helpful when it identifies cultural values and assumptions of even the actual texts and contexts that, again, none of us seem totally free from (thus why past theologians like Emil Brunner and likely Rudolph Bultmann spoke of the bible containing the word of God but not in itself, every word or syllable, necessarily being the word of God).

But thanks for sharing this Padilla address and its import, Flyn.