Whitby Abbey has left some impressive ruins.

Some may have noticed that I haven’t been posting anything for the past while. That’s because Margaret and I were away for almost two months – we spent a couple of weeks in Norway, a month in the UK and several days in Tunisia.

We met long-lost relatives in Norway, stayed with old friends in England and with family in Tunisia. We visited numerous castles and archeological sites, took long walks, ate lots of good food (believe it or not!) and reveled in breath-taking views.

There were challenges along the way, especially while driving 8,000 kilometres around Britain, from Land’s End to John O’Groats and the Orkneys, sometimes on very narrow roads and quirky roundabouts.

But that’s another story. I will focus here on some of the sacred sites and spiritual insights we experienced along the way.

Those who have eyes

Borgund Stave Church is one of just 28 left in Norway.

Europe is often described these days as ‘post-Christian,’ and it is certainly true that the faith does not occupy the central role that it once did.

But signs of the church’s influence are everywhere, for anyone who is inclined to notice. We have an amazing heritage – the lives and achievements of our Christian brothers and sisters deserve our continued attention.

- Norway

The stave (wooden) churches of Norway are architectural marvels. During the Middle Ages, more than a thousand were dotted around the countryside; now just 28 remain.

We visited Ringebu Stave Church, north of Oslo, situated on St. Olav’s Way, a pilgrim route. We also made a special trip to the rather remote Borgund Stave Church.

While in Bergen we went to Fantoft Stave Church, which illustrates the value still placed on these treasures by the general population. The church was one of several burnt down in the early 1990s by Norwegian ‘black metal’ musicians. It was completely rebuilt by 1997.

Margaret with her second cousin, Jan Fredrik, at the prayer house in Stavanger.

Another highlight was visiting a prayer house in Stavanger on the southwest coast – apparently the last one still in use as a Christian mission from a network created by the 19th century Haugean reform movement. Not nearly as impressive visually as the stave churches, the prayer house can be found on a shopping street in the downtown core.

Hans Nielsen Hauge led a renewal movement in the Lutheran state church of Norway. Margaret’s family was shaped by the movement, both in Norway and after they migrated to the United States.

She and her 88 year old second cousin, who generously shepherded us around the town, are descended from a common ancestor who helped to fund and create the prayer house.

- Britain

Influential theologian Richard Hooker in front of Exeter Cathedral.

We visited many impressive religious sites along the way, including major cathedrals at Chichester, Salisbury, Wells, Exeter, York, Canterbury and London (St. Paul’s).

We spent the first week driving along the south coast to Land’s End in Cornwall, then back along the north coast of Cornwall/Devon/Somerset to our friends’ home in Cambridge. Then north along the east coast, counterclockwise around all of Britain to Wales, and back to Cambridge, Canterbury and London.

Some of our favourite stops:

- Holy Trinity Headington Quarry is a short walk from C.S. Lewis’s home at The Kilns (which we also visited). He attended the church for over 30 years and is buried there. The vicar interrupted a parish meeting to show us his grave. A BBC video on the church’s site gives a lovely view of the area, including what is now the C.S. Lewis Nature Reserve, just behind his house, where he used to swim.

-

St. Michael’s Mount, like Mont-Saint-Michel in northern France, is a tidal island.

St. Michael’s Mount, near the western tip of Cornwall. Edward the Confessor gave the site to the Benedictine order of Mont-Saint-Michel in the 11th century. Like Mont-Saint-Michel on the north coast of France, it is a tidal island. A castle was later built on the site and since the English Civil War it has been home to the St. Aubyn family

- Whitby Abbey, on the coast in Yorkshire, is now in ruins (pictured above). It was the site in 664 AD of the Synod of Whitby which took place to resolve the question of whether the Northumbrian church would adopt and follow Celtic Christian traditions or adopt Roman practice. The abbey is also – probably more widely – known as the inspiration for Bram Stoker’s Dracula. And Whitby is a beautiful little port town, where Captain Cook learned his craft.

-

Constantine the Great was proclaimed Roman Emperor in York.

Constantine the Great was proclaimed Roman Emperor on or near the grounds of York Minster in 306 AD. News to me! The man known for ruling from Constantinople – and for declaring tolerance for Christianity in the Roman Empire – began his reign in northern England. He was not a Christian at the time, but by 325 he convened the First Council of Nicaea, which produced the Nicene Creed.

- Lindisfarne, also called Holy Island, is a tidal island off the northeast coast of England. Historic UK says: “Possibly the holiest site of Anglo-Saxon England, Lindisfarne was founded by St. Aidan, an Irish monk, who came from Iona, the centre of Christianity in Scotland [in the 7th century].” We attended the Anglican church there, which does not seem to be contributing to Lindisfarne’s new agey reputation. It featured a relatively recent letter from the Bishop of Nidaros Cathedral (Trondheim, Norway) apologizing for all those unpleasant Viking raids a millennium ago.

-

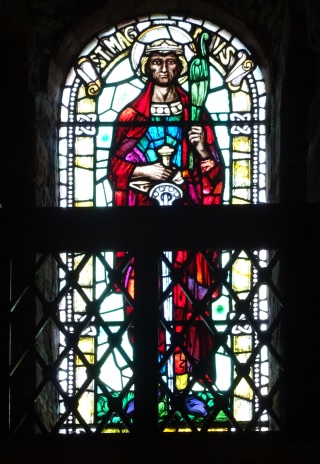

St. Magnus, at the cathedral.

St. Magnus Cathedral, the oldest in Scotland, dominates the skyline of Kirkwall, the main town of the Orkneys, off the north coast. The church’s site notes: “The worshipping community over the centuries has been part of the Roman Catholic Church, the Norwegian Church, the Scottish Episcopal Church, and the Church of Scotland (Presbyterian).” Cathedral Minister Fraser Macnaughton quoted from scholar Linda Mercadante, who we knew when she attended Regent College.

- St. David’s Cathedral, near the southwest coast of Wales, was built in the 12th century on the site of a monastic community founded by Saint David, who died in 589. In 1123, Pope Callixtus II declared that two pilgrimages to the Cathedral were equal to one journey to Rome. We attended a lovely choral evensong service there.

These were amazing sites, well worth seeking out. But every day we drove by many village churches and parish churches in cities. Some of them were beautiful, but all demonstrated the longterm significance of churches in their communities.

It is true that some churches have been sold for other uses – housing, stores, pubs, even mosques. One short stretch of Church Street (ironically) in Barmouth, Wales was a sad site. Two former churches had been converted into stores; just a little further along was a remaining chapel, open though not in great repair.

- Tunisia

This baptistry in Bardo Museum comes from a 4th century parish church east of Tunis.

Tunisia is a Muslim nation now, but that was not always the case. Visiting St. Vincent de Paul Church on our very first full day in Tunis, we saw pictures of several early Popes/Martyrs: Victor, Miltiade and Gélase. And Saint Augustine, of course, who was educated in Carthage.

As Gina Zurlo said in Global Christianity (Zondervan Academic, 2022):

Christianity has a long history in Tunisia, dating to the 1st century. As Arab Muslims took over the region in the 7th to 8th centuries, the region slowly transitioned from Latin-speaking Christian Berbers to Arabic-speaking Arab Muslims. Christianity disappeared by the 12th to 13th centuries.

Various sites featuring Carthaginian and Roman ruins on the coast just northeast of Tunis testify to the rich Christian culture which once flourished there. The Bardo Museum in Tunis is full of mosaics and other artefacts which reflect the same reality.

Signs of new life

Fortunately, there are signs of new life, along with the many signs of persevering faith, in each nation we visited.

In Trondheim, on the west coast of Norway, we were able to attend two services at the beautiful old Nidaros Cathedral (begun in 1070, completed in 1300, rebuilt as a ‘national symbol’ beginning in 1868).

Young Christians now use the Hauge prayer room as a base from which to reach out to the community around them. We also heard of a group hosting an evening event at a local bar in Stavanger.

Chipping Norton Community Church meets in the Town Hall.

In England, we attended Chipping Norton Community Church in the Cotswolds, a sister church to West Coast Christian Fellowship, our church in Vancouver. Pastor Jon Room had visited us earlier in the year and hosted us on our visit there.

The church meets in the Town Hall, right on the main street; the mayor is a member. The congregation is active in social service work (Christians Against Poverty Debt Centre, food bank, toddler group) and also in evangelism.

One of the most encouraging times was during our stay in Cambridge. We saw many more signs of Christian faith as we walked the streets than we ever do in Vancouver.

Apart from the impressive chapels which adorn each of the colleges (Trinity, King’s, Magdalene, etc), we came across a very active Baptist street church which offers all kinds of services to refugees, new immigrants and others. Then we met street evangelists sharing the gospel. We took part in a couple of home group meetings involving young, well educated and hospitable Christians.

Freswick Castle is just a few minutes from John o’Groats in northern Scotland.

We spent a short time at Freswick Castle in the far north of Scotland, a private home which regularly hosts events, especially for Christians who are members of the arts community. We had a glimpse into the importance of such a retreat for creative/faithful people.

In Caerleon, Wales, we ‘happened’ upon a nondenominational service where two women spoke in place of the sermon. They were both a moving testament to the grace of God.

Near the end of our time in England we attended Evensong at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. We were amazed to find ourselves surrounded by hundreds of people, late on a Monday afternoon. Our experience in the past has been that such events draw far fewer people.

Tunisia is a very different case than the UK or Norway, but while only.0.2 percent of the population is Christian, according to Global Christianity, there are several small churches active in the nation.

God’s timing

We saw many signs of saints and martyrs along the way. Many early Christians gave their lives to ensure that the gospel reached the far corners of their lands.

The early Christians were by no means perfect (writing in the 8th century, for example, Bede described some unseemly debates over the proper dates to celebrate Easter, etc as the Roman Christians asserted their dominance over the indigenous Celtic Christians).

But things were to decline further over the centuries, as the church became increasingly entangled with the state – persecution of both Protestants and Catholics in the wake of Henry VIII’s separation from Rome, the participation of Puritans and various types of Anglicans during the Civil War, the involvement of (some) missionaries in Britain’s imperial conquests.

The list of dubious church actions is long – and one is left to wonder whether we might indeed be in dire need of a post-Christian correction of course.

World Christianity

One result of Britain’s colonial activity is that it is now one of the most multicultural nations in the world. We could have – but sadly didn’t – visited one of the many churches being planted by Nigerians, Brazilians, Indians, Chinese and others around the country.

As a centre of missionary activity during the 19th and 20th centuries, it is now home to several institutes which are tracking the development of a new form of World Christianity. I was able to speak with the leaders of two of those bodies during our trip.

- Oxford Centre for Mission Studies

Tom Harvey is Academic Dean of the Oxford Centre for Mission Studies.

Dr. Tom Harvey is Academic Dean of the Oxford Centre for Mission Studies, whose vision is “The global church equipped to participate in the realisation of God’s transforming mission through research and applied scholarship.”

He spoke with me on the grounds of centre, which is comfortably housed in St. Philip and St. James Church. He said the OCMS founders began by turning the traditional missions approach – “from the West to the rest” – on its head, looking first to the Two-Thirds World and learning from them.

In fact, they begin further back than that: “We do not begin mission at Matthew 28, we begin mission at Genesis 1 and 2.”

- Cambridge Centre for Christianity Worldwide

Muthuraj Swamy is Director of the Cambridge Centre for Christianity Worldwide.

A couple of days later I spoke with Dr. Muthuraj Swamy, Director of the Cambridge Centre for Christianity Worldwide.

Though he is not particularly critical of the West or its missions history, he does believe the World Christianity needs to be put into a broader perspective: “The word ‘world’ is, and ought to be, all encompassing.”

Swamy said there have been three phases in missions / World Christianity:

- From the West to the rest (traditional missions).

- The West and the world (still thought of separately).

- His approach: “connecting Christians,” both in terms of ecumenical relations and geography.

[October 30 note: John Stackhouse has written a good piece on priest/missionary/linguist Henry Martyn; the CCCW was originally named the Henry Martyn Centre.]

Chatting with Tom Harvey and Muthuraj Swamy made me wonder whether ‘post-Christian’ is a good description for the UK (or Norway). Maybe we ought to think, rather, from a broader perspective.

Who knows what God may have in store for nations which have been devoted (however imperfectly) to the faith and whether, with their rich Christian histories, they might not be part of a new story involving the likes of Tunisia, and the rest of the world.

At any rate, Margaret and I feel privileged to have seen and experienced what we have, and we are happy to be home safely in order to play our small part in God’s beyond-our-comprehension mission.