Statistics Canada released an ‘Insights on Canadian Society’ study by Louis Cornelissen October 28 titled ‘Religiosity in Canada and its evolution from 1985 to 2019.’

Statistics Canada released an ‘Insights on Canadian Society’ study by Louis Cornelissen October 28 titled ‘Religiosity in Canada and its evolution from 1985 to 2019.’

Following are two portions of the 18-page report – the overview and the section on British Columbia.

Overview

In recent decades, the religious landscape in Canada has undergone significant changes, including a decline in religious affiliation and the practice of religious activities, both collectively and individually.

Data from several cycles of the General Social Survey were used in this study to paint a portrait of the diverse relationships Canadians have with religion. The study also presents key trends in the evolution of religiosity in Canada since 1985.

• In 2019, 68% of Canadians aged 15 and older reported having a religious affiliation. In addition, just over half of Canadians (54%) said they considered their religious or spiritual beliefs to be somewhat or very important to how they live their lives. Participation in group or individual religious activities was less common: 23% of Canadians said they participated in a group religious activity at least once a month, and 30% said they engaged in a religious or spiritual activity on their own at least once a week.

• Overall, reporting a religious affiliation is not necessarily related to placing a high importance on religion in everyday life. In fact, during 2017 to 2019, nearly one in five Canadians (18%) reported having a religious affiliation while indicating that they rarely or never participated in group religious activities, never engaged in religious or spiritual activities on their own and considered their religious or spiritual beliefs to be of little or no importance to how they live their lives.

• In recent decades, there has been a decline in religious affiliation, participation in group or individual religious or spiritual activities, and the importance of religious and spiritual beliefs in how people live their lives. Changes in indicators of religiosity over time appear to be the result of differences between younger and older cohorts.

• Compared with individuals born in Canada, those born outside Canada were more likely to report having a religious affiliation, to consider their religious and spiritual beliefs important to how they live their lives, and to engage in religious activities in groups or on their own. These differences were more pronounced among younger birth cohorts.

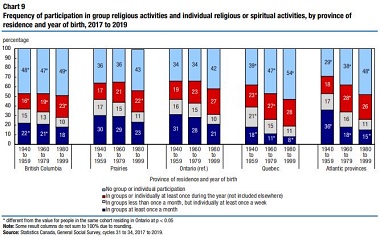

• There were some differences in religiosity across the country. For example, in British Columbia, religious non-affiliation was more common and generational differences in religious practice were smaller. In Quebec, religious affiliation was higher, but was more often combined with lower importance given to religious or spiritual beliefs. Religious practice was also generally lower in Quebec. Lastly, in the Atlantic provinces, the generational differences were larger than elsewhere in the country

British Columbia

In British Columbia, a strong disaffiliation trend and stable but low participation in religious activities

From 2017 to 2019, British Columbia has been characterized by large proportions of people who reported having no religious affiliation (40%) and never having engaged in any group or individual religious or spiritual activities in the past year (47%).

High proportions of non-affiliation have distinguished British Columbia for several decades. For example, in 1985, 25% of people aged 15 and older living in British Columbia reported having no religious affiliation, compared with 9% in the rest of Canada. Data from the 1901 Census show that even then, a higher proportion of British Columbians reported having no religious affiliation (1.5%, compared with 0.16% elsewhere in Canada).

They were also less likely than their counterparts in the eastern provinces to attend churches and places of worship.17 Various studies have attempted to link this distinctive regional difference to historical circumstances. It has been suggested that the establishment of religious organizations in British Columbia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries may have been more uneven than elsewhere in Canada, leaving more room to religious non-affiliation.

It has been suggested that British Columbia’s unique non-affiliation situation may be attributable to the high level of immigration from East Asia (particularly China) as many of these immigrants do not report a religious affiliation.

However, overall, immigrants and the children of immigrants in British Columbia were less likely (36%) than people in the third generation or more (45%) to report having no religious affiliation.20 Thus, the province’s unique situation is not simply a matter of immigration, or at least not recent immigration.

This non-affiliation trend was even more pronounced among younger cohorts. For example, from 2017 to 2019, more than half (53%) of people born between 1980 and 1999 reported having no religious affiliation, compared with 38% of those born between 1960 and 1979 and 27% of those born between 1940 and 1959.

Most notably, the proportion of people who simultaneously reported having no religion and placing little or no importance on their beliefs was greater among the younger generations.

However, these intergenerational differences in affiliation and importance of beliefs do not translate into significant differences in group or individual religious or spiritual activities. The proportions of people who participated in a group religious activity at least once a month (between 18% and 22%) and those who did not engage in a group or individual religious activity in the past year (between 47% and 49%) were similar across cohorts.

For the full 18-page study go here.

The study relied on a number of sources, including one book by Reg Bibby and several publications by Joel Thiessen and Sarah Wilkins-Laflamme. For articles on Church for Vancouver about the latter two go here.

As an Anglo-Canadian born and raised in Vancouver, I am very certain the drop in ‘religiosity’ in BC is not due in any part to immigration. It is a phenomenon from within, and it is, I dare say, a ‘white’ phenomenon at its roots.

It is a rise in secularism, which began in higher education in the United States as Ivy League institutions founded as seminaries cast aside their spiritual roots in favour of secularism and status. They have been elite but also spiritually dead for generations, as evidenced by Harvard’s appointment this year of an atheist as Chaplain, a move which raised no eyebrows but brought praise from the student body for the selection of someone so ‘open minded.’

The benefits of academic prestige and the $$$$$$ that it brings in terms of elite students and research funds from both domestic and international sources, has not been lost on Canadian universities such as UT, McGill and UBC, which have never been religious in their character or aims.

It has been about science especially, and with the introduction of theory of evolution into the academic community, it has been about explaining life and the universe, and meaning, in the absence of any conception of a Creator. Philosophy, sociology, anthropology and psychology have bought into the idea of existence, meaning and fulfillment without a Creator and without a need for, and even disdain for, the moral absolutes tied to belief in the existence of an almighty Creator.

This academic secularism has been bolstered by the presence of Marxist ideas in both economics and political science, ideas which likewise provide no room for religiosity, let alone the concept of a Creator. Mankind is intelligent, mankind is capable, and mankind – in the absence of a moral code saying otherwise – is good.

With the appointment of graduates from secular institutions in sectors such as education, law, health and government, it is no wonder religiosity is so low in this country, especially when public education across the country is in the hands of so many secular minds in the classroom, school boards and members of ministries of both public and higher education from coast to coast.

Secularists no doubt applaud this development, but they forget one thing. Ignoring the spiritual leaves a void in the heart, and that void is the hope for the spiritual revival of this country.