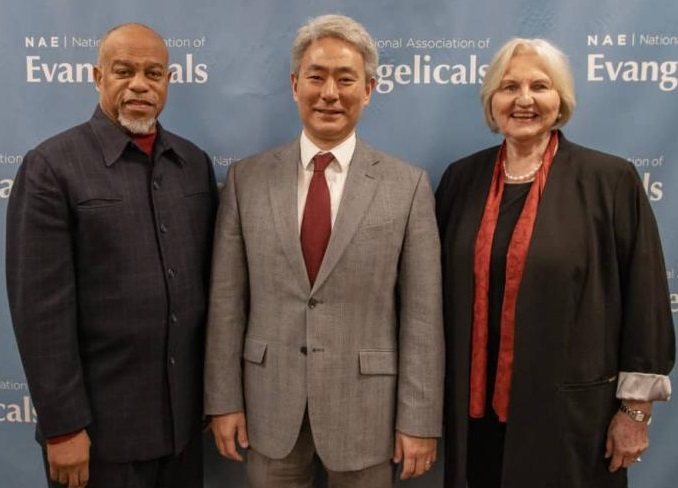

Walter Kim (centre) is the newly elected president of the National Association of Evangelicals in the U.S. One of his major challenges, surely, will be providing evidence that the NAE is not a political movement dominated by white evangelicals.

Next week I will be taking part in the World Evangelical Alliance General Assembly near Jakarta, Indonesia.

I am looking forward to the trip (which will begin with several days in Singapore) for several reasons, not least to answer questions like: Who is an evangelical? What is the shape of evangelicalism today? Does evangelicalism have a future?

American evangelicalism

These questions are being discussed widely (ad nauseam in some quarters). Most of the commentary lacks perspective, being very American and largely ahistorical.

Just this morning, for example, before settling down to write, I saw this tweet: “Make no mistake about it: evangelicalism is white supremacy disguised as religion.”

Fortunately, a good response to simplistic assessments has just been published by Yale University Press. The answers proffered by Thomas Kidd in Who is an Evangelical? benefit anyone interested in the topic, including one headed to an international conference of evangelicals. I’ll quote from the book before briefly discussing the international situation and the General Assembly itself.

The book’s subtitle – The History of a Movement in Crisis – suggests why Kidd wrote this concise (191 page) book:

The book’s subtitle – The History of a Movement in Crisis – suggests why Kidd wrote this concise (191 page) book:

This book is an attempt to introduce readers to evangelicals’ experiences, practices and beliefs, and to examine the reasons for our crisis today. I hope that scholars will find the book valuable, but it is mainly written for other people – journalists, pastors, people who work in politics and more – who are interested in what makes evangelicals tick.

Who is an Evangelical? is for people who might ask, “What has happened to evangelicals?” They were supposedly a religious movement, but now they seem to show up only on election day to vote Republican, regardless of who that Republican is. My hope is that this book will show that there is far more to the evangelical story. The narrative of white evangelicals’ corrupt quest for Republican power is not false. But it is incomplete.

Kidd says that early evangelicals

. . . were Christians who believed in the message preached by George Whitefield and his successors [in England and the United States in the mid-1700s]. Whitefield’s message was that all people – regardless of church membership, ethnicity or social standing – needed the ‘new birth’ of salvation through Jesus Christ. The Holy Spirit would change the hearts of true believers, empowering them to live God-honoring lives. . . .

He points out that the problems now besetting evangelical Christianity have deep roots.

Some evangelicals (John Newton, William Wilberforce) led the anti-slavery movement while others strongly defended the practice; Whitefield himself supported slavery. Evangelicalism “contains a powerful egalitarian impulse,” according to Kidd, “but white evangelicals have often been reluctant to let their spiritual beliefs inform their views of racial oppression and inequality.”

He describes how the movement became politicized, especially in the past 70 years. After tracing evangelicals’ political involvement right from the 1740s in issues such as slavery, crusades against poverty, temperance campaigns and opposition to teaching evolution in school (the Scopes trial), Kidd writes about the leader probably most closely linked to modern evangelicalism:

No other evangelist has spoken more widely and compellingly about the need to be born again than [Billy] Graham. . . . But Graham’s influence in Washington, D.C. gave white evangelicals a taste of political power as well. If they could sustain the access that Graham possessed, it could help them save the nation, they thought.

They could preserve Christian civilization from atheistic communism and the secular godlessness that seemed to menace America after World War II. The new politicization of evangelicals in this period began not with the culture wars of the 1960s and 1970s, but with their reaction to the Cold War and communism in the decades following World War II. . . .

Politically engaged evangelicals embraced contradictory priorities, however. They called on the nation to return to a nostalgic past of Christian cultural establishment while exhorting individuals to reject mere cultural Christianity and to be born again. Sometimes it is not clear whether individual conversion or national political influence was their real priority. But these evangelical political insiders were eager to enlist nonevangelical politicians when necessary to regain cultural power.

The desire of many white evangelicals to reestablish political influence is at the root of their identity crisis today. That crisis began in the 1950s, became more acute in the 1980s with the advent of the Moral Majority, and went atmospheric with white evangelical voters’ overwhelming support for Donald Trump in 2016.

By 2016, many critics (some within evangelicalism itself) were wondering whether there was anything substantially spiritual about the movement any more, or if evangelicals’ God-talk just masked earthly ambitions for power.

Kidd describes himself as an evangelical and retains some hope for the future:

White evangelicals’ uncritical fealty to the GOP is real, and that fealty has done so much damage to the movement that it is uncertain whether the term evangelical can be rescued from its political and social connotations. . . .

Perhaps I am naive to hope that there remains a core of practicing, orthodox evangelicals who really do care more about salvation and spiritual matters than access to Republican power. . . .

Striking the right balance between eternal and worldly concerns is a common struggle for people of faith. Evangelicals carry the additional burden that their political behavior is constantly scrutinized, yet they no longer control the definition or perceived composition of their movement. . . . Surveys commonly use self-identification to define who counts as an evangelical, a method that usually tells us more about public impressions and the political behavior of the movement than about the beliefs and spiritual habits of the interviewees.

Here is where Kidd puts his trust:

But there’s an older version of evangelicalism – one in continuity with the history of the movement – that still exists in America and around the world. . . .

What, then, makes an evangelical an evangelical? Evangelicals’ political behavior is important, and it has a troubling history. But at root, being an evangelical entails certain beliefs, practices and spiritual experiences. Historically, evangelicals are a subset of Protestant Christians.

They see conversion and personal commitment to Jesus as essential features of a true believer’s life. They cherish the Bible as the divinely inspired Word of God. They believe that real Christians have a personal relationship with God, mediated by the guidance of Scripture and the power of the Holy Spirit. They aspire to act on those beliefs by praying, attending worship services, witnessing to the lost, studying the Bible, going and sending people on missions, and ministering to the ‘least of these.’

Partisan commitments have come and gone. Sometimes evangelicals have made terrible political mistakes. But conversion, devotion to an infallible Bible and God’s discernible presence are what make an evangelical an evangelical.

Could things change in the United States?

David C. Kirkpatrick reminds us in a recent Washington Post article that there remains a well established ‘evangelical left.’ He also points to the broader evangelical movement which could influence North America:

But a global tradition of left-leaning evangelicalism has the potential to reshape the U.S. political landscape. If we shift our gaze from the U.S. political right, we can see an alternative tradition of evangelicalism that embraces social, economic, environmental and racial justice. As Christianity continues to grow and flourish across Africa, Asia and Latin America, understanding the diversity of the faith provides a window into a potential future of American evangelicalism.

The 20th century witnessed a tectonic shift in Christianity’s demographic center: In 1900, nearly two-thirds of Christians lived in Europe; today less than a quarter do. Yet as Christians have become less white, white American evangelicals representing the most conservative segment of the religion played an increasingly outsize role around the world even as their slice of the demographic pie diminished.

Kirkpatrick may be overstating the left-leaning nature of evangelicalism worldwide, and its potential effect on American politics, but he is certainly on to something.

Canada

Several scholars regularly point out that evangelicalism in Canada is not the same as in the States. John Stackhouse, for example, recently wrote:

I’m only going to say this one more time. Canadian evangelicals are not identical with our American cousins and not all aligned with the political right.

Along with a couple of others, I’ve been saying this publicly now for almost 30 years, and our fellow scholars have gotten the word. The textbooks read differently than they used to when they describe evangelicalism in Canada.

Most of the news media, however, along with most of the courts, political parties and educational leaders, seem to have missed the memo. . . .

Go here for the full comment.

Rest of the world

And if Canadian evangelicalism doesn’t mirror the American version, that applies even more to most corners of our very diverse world. Brian Stiller, former head of the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada and now director of global development (following several years as global ambassador) for the World Evangelical Alliance, recognized the American contribution to the growth of evangelicalism in a recent article:

It is hard not to think that we are standing at a turning point in history. The 16th century Protestant break with Rome brought with it a new vision and understanding of the Gospel. In the long sweep of that story, the American vision and energy for missions, led by extraordinarily courageous and generous men and women, was driven by a faith that new life was to be found in Jesus Christ.

The new understanding of the Holy Spirit birthed in America during the 20th century produced an unprecedented revival that encircled the globe. In 1960 there were some 90 million Evangelicals worldwide; today there are 600 million. . . .

Kidd is clear: “my account is focused on North America and is deliberately limited in scope.” There are many good books describing the breadth and dynamic growth of world evangelicalism, and I am looking forward to meeting some of the people who lead the movement around the world.

General Assembly

Bishop Efraim Tendero urged ‘peace building’ with Muslims when he spoke at the Global Conference on Human Fraternity in Abu Dhabi earlier this year.

I expect to see signs of the future configuration of evangelicalism at the General Assembly of the World Evangelical Alliance when delegates meet November 7 – 13 just south of Jakarta, Indonesia.

The World Evangelical Alliance is

. . . a global ministry working with local churches around the world to join in common concern to live and proclaim the Good News of Jesus in their communities. WEA is a network of churches in 129 nations that have each formed an evangelical alliance and over 100 international organizations joining together to give a world-wide identity, voice, and platform to more than 600 million evangelical Christians.

Seeking holiness, justice and renewal at every level of society – individual, family, community and culture, God is glorified and the nations of the earth are forever transformed.

Bishop Efraim Tendero from the Philippines was appointed Secretary General and CEO of the World Evangelical Alliance (WEA) on March 1, 2015. He has previously served as national director of the Philippine Council of Evangelical Churches.

On a personal note, I appreciate the work that the major ecumenical bodies do, and have benefited from seeing it firsthand – as a volunteer at the peace and justice coffee house during the World Council of Churches’ 6th Assembly in Vancouver (1983) and as a delegate to the Third Lausanne Congress on World Evangelization in Cape Town (2010).

I hope to write a couple of articles about the next couple of weeks in Singapore and Jakarta, though when exactly they are posted will depend on my schedule.

Hi Flynn–

This was a very interesting article, dealing concisely with some very complex matters. Hope your trip is enjoyable and informative.