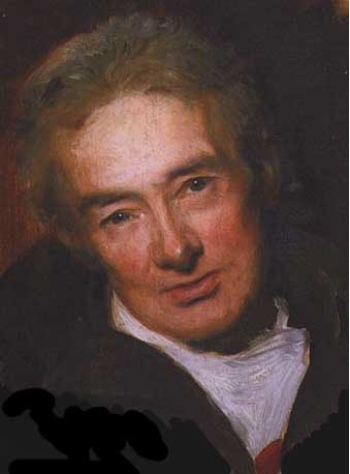

Young social activists would do well to study the career of William Wilberforce, who led the fight against slavery in Britain.

Many people know that William Wilberforce led the fight against slavery in the British Empire two centuries ago. But Paul Chamberlain, who teaches at Trinity Western University and ACTS Seminaries, will highlight some of the lessons he has for our generation next Thursday (March 19) in William Wilberforce: A Success Story in the Battle for Social Justice.

The following article is based on two of Chamberlain’s books: Why People Don’t Believe: Confronting Seven Challenges to Christian Faith (Baker Book House, 2011) and Talking About Good and Bad Without Getting Ugly: A Guide to Moral Persuasion (InterVarsity Press, 2005).

In 1787 [William Wilberforce] wrote: “Almighty God has set before me two great objectives: the abolition of the slave trade and the reformation of manners (i.e., morals).”[1] With those words, an epic struggle began against the entrenched evils of his day in English society.

Why did he succeed? When one looks at his life, there are a number of lessons we can learn which not only accounted for Wilberforce’s success, but can also contribute to our effectiveness in bringing about moral and social change in our own culture.

1. Moral and social justice are indivisible

The first lesson for us is that Wilberforce saw social justice as an indivisible whole and not as a group of individual practices that could be addressed in isolation from the others. Morality was a matter of one’s heart.

If a person had grown cold toward social justice, that coldness would work itself out consistently in one’s willingness to tolerate a whole range of unjust practices. Wilberforce understood that the same hearts that allowed human slavery would eventually tolerate other injustices as well.

This truth was plainly evident in English society. Not only was slavery accepted, but child labour as well. Young children worked up to 18 hours a day in cotton mills or coal mines for a few shillings a month.

Furthermore, while British subjects in India were suffering grim treatment at the hands of Wilberforce’s countrymen, harsh debtor laws were keeping many poor English citizens in prisons at home. They were held in prison until they could pay their outstanding debt but, of course, being in prison allowed them no opportunity to earn money to pay off the debt.

Public executions occurred frequently, often as public sport, with young petty thieves being executed in the same ceremony as serious criminals while excited crowds looked on. Meanwhile, on the streets of London hordes of prostitutes (estimated at one-quarter of the women in the city) sold their bodies in increasingly degrading practices.

All of these injustices had become part of the established economic and political structure of England, and Wilberforce saw a connection between them all. He attacked these practices on both personal and institutional levels.

During his lifetime Wilberforce regularly gave away one-quarter of his income or more to the poor. He personally paid the bills of many people in prison under the debt laws so they could live productive lives.

Along with others, he organized the Society for the Education of Africans, the Society for Bettering the Condition of the Poor and the Society for the Relief of Debtors, which obtained the release of 14,000 people from prisons.

2. A matter of careful strategy

A second lesson for us is . . . that the fight for social justice requires a careful strategy and Wilberforce [who spent 45 years as a Member of Parliament] employed one. Very little was left to chance. In attacking slavery, his strategy included at least three elements that we would do well to emulate.

Inform and be informed

Facts. Information. Data. We tend to underestimate the importance of these, but if you have ever attempted to make a case for a cause or viewpoint you believe in, you will know only too well how quickly and resoundingly a shortage of necessary facts can shatter your case. Whether it is details of the practice under consideration, historical data related to it, relevant statistics or knowledge of the other side of the issue, getting the facts usually requires pain-staking research and high levels of both tenacity and energy.

Wilberforce worked with facts, many of which were not known to the English public. How many knew, for instance, that slaves were rounded up in Africa, chained, held, then sold to the highest bidder who had come into port? The elderly and unfit were shot or clubbed to death while others, screaming and pleading for mercy, were loaded onto ships, shackled into irons and forced into vile holds where the stench of human waste and vomit was overwhelming.

There the slaves lay on their sides crammed so tightly together that the chest of each was pressed against the sweaty back of the next. Many would die on each trip while others, driven insane, would be killed by the crew. Meanwhile, the crew had the pick of the slave women, making the ship “half bedlam, half brothel,” as one captain put it. . . .

Getting the facts required great effort and expense in research and travel, but he knew that without them he had nothing with which to oppose the powerful economic and political establishment that had come to depend upon this trade for its prosperity and power.

Through pamphlets and speeches in the House of Commons and elsewhere, he made these facts known to an often shocked public. Armed with them, he called slavery a “national crime” and “a course of wickedness and cruelty as never before disgraced a Christian country.”[2]

Anyone could say these words, even with great dramatic flair, but only someone with the facts to support them could say them with credibility and, thereby, grab the sustained attention of the public. These facts, once made known to the public, spoke for themselves. They made it impossible for Wilberforce’s opponents to ignore his severe descriptions of slavery or treat such descriptions with disdain. . . .

Have answers for opponents

We’ve all seen people confidently express their own view on an issue and voice disdain for an opposing position. Perhaps we have done it ourselves. . . .

Understanding opposing views, and what can be said in favour of them, is just not something we come by naturally. We usually have to be pushed into it. But forcing ourselves to do this is indispensable if we hope to effectively engage others and bring about real positive change in our culture. . . .

Wilberforce familiarized himself with his opponents’ arguments against his claims and developed thoughtful and compelling responses to them, responses which were guided by other specific foundational moral truths.

His opponents argued that slaves were not truly human but were, in the words of one court decision, simply chattels. The same decision had established that a ship’s captain had the right at law to dump as many overboard as he wished “without any suggestion of cruelty or surmise of impropriety.”[3]

This had become common opinion concerning the moral status of the slaves. Human-ness had been, in effect, redefined in such a way that the slaves were not included in its definition and the consequences were breathtaking. If slaves were not human there was no moral duty to treat them as though they were.

This common assumption allowed the opinion makers of the day, and indeed the general English public, to treat slaves in the grisly manner they did, and at the same time claim to have a high regard for humanity.

Further, his opponents argued that Wilberforce’s view that slaves were human was merely his own personal religious view and ought not to be imposed on others as public policy. “Humanity,” argued the Earl of Abingdon on one occasion, “is a private feeling, not a public principle to act upon.”[4]

Supporters of the slave trade also argued that the economy would suffer a fundamental upset if this institution were abolished. Abolition would instantly annihilate a trade that annually employed upwards of 5,500 sailors and 160 ships, and whose exports amounted to 800,000 pounds.

Wilberforce, and Abraham Lincoln shortly after him fighting the same battle in America, responded by continually returning to the question of the humanity of the slaves. In their own ways they pointed out the confused moral perspectives of the slave traders, in keeping with another foundational moral truth. This provided a basis for urging these traders to abandon their moral positions.

They did this by reminding their opponents that try as they might they could not escape the reality that the slaves really were human and they knew it.

Didn’t supporters of the slave trade have sex with slaves? Didn’t supporters allow their children to play with the children of the slaves? Didn’t supporters treat the slave trader with contempt due to the despicable nature of his work? Such behaviour on the part of Wilberforce’s opponents made no sense, he argued, if slaves were not human. In fact, it was utterly confusing with tragic results.

But if slaves were truly human after all, then slavery was not merely a religious matter, argued Wilberforce, appealing to yet another foundational moral truth. He refused to allow his moral position to be written off as merely his own religious perspective. One did not need to be religious to know that humans ought not be treated in the way the slaves were.

Furthermore, it made little difference to the argument that dire economic consequences could result from ending slavery. If the slaves really were human, then slavery was immoral and foul regardless of the economic consequences. And the responses went on and on, each preceded by a careful understanding of his opponent’s arguments.

Point our fingers backward, not just forward

Anyone who has tried to argue someone out of a viewpoint has probably experienced the surprise of having the person whose mind he was seeking to change, become defensive and actually begin to stick up for his viewpoint even more passionately than before. . . .

William Wilberforce did not share this pessimistic view of debate, but he did appear to understand this reality about argumentation very well. He knew that if his arguments against slavery or child labour or debtor laws or any other shameful practice turned into accusations or attacks on the people who advocated these practices, or even if they were perceived as such, they would tend to have the opposite effect of what he was hoping for. Rather then moving people from these practices, they would likely make them even fiercer defenders of them.

How did Wilberforce deal with this reality? Not by giving up on debate altogether. For a parliamentarian such as Wilberforce, that option was unthinkable. Rather, he demonstrated unusual wisdom in choosing an approach we can learn from.

With a stroke of genius – and humility – he went beyond simply avoiding personal attacks, and actually took great care to include himself in the guilt whenever he attacked any shameful practice. . . .

“I mean not to accuse anyone,” he said, “but to take the shame upon myself, in common indeed with the whole Parliament of Britain, for having suffered this horrid trade to be carried on under their authority. We are all guilty – we ought all to plead guilty, and not to exculpate ourselves by throwing the blame on others.”[5] . . .

The genius of this approach is that it made it virtually impossible for anyone to feel personally attacked when Wilberforce called upon his country to abandon certain reprehensible practices. He was as much at fault as anyone else and he said so. Consequently, the need for his opponents to defend themselves would be reduced and the way made easier for them to consider moving away from these practices.

3. Maintain humour in the midst of serious work

A third lesson to learn from Wilberforce is a surprising one, namely, that humour is to be cherished, no matter how serious the work one is involved in. . . .

But can we really maintain a humorous outlook when the work we are engaged in is deadly serious? Should we do so? As difficult as it may be for some to see how Wilberforce could laugh, knowing the repugnant facts he knew about the slave trade and other injustices in his culture, he maintained a powerful wit and sense of humour throughout his lifetime. . . .

How could anyone be this funny knowing slaves were being rounded up, brutalized and killed, children were being treated inhumanely in the country’s underground mines and many of his countrymen were being held in prisons by ruthless debtor laws, all while he laughed?

Isn’t such laughter cruel and insensitive, the sign of a hardened heart? In Wilberforce’s case, nothing could be further from the truth. Such descriptions simply did not fit. At the same time as he was demonstrating such joviality, he was also giving his energy, time, skills, wealth and, in the end, his very life to fighting these shameful practices and to making life better for the people suffering under them. Cruel and insensitive, he was not. There had to be some other explanation for his humour and wit.

Two facts may help us understand how this was possible for Wilberforce, and is for us as well. First, we should, at the very least, realize that maintaining a dour gloomy outlook does nothing to make us more effective in bringing about cultural change. It neither makes our message more appealing nor does it make life one iota better for those for whom we are trying to effect change. In fact, the opposite is usually true. The more energetic and positive we come across, the more likely people will be to give us a hearing.

Secondly, let us not forget that working against shameful and cruel practices such as Wilberforce was opposing is fundamentally positive work. This is a truth often missed because of how negative it seems to most of us to be working against anything, like slavery or child labor, or debtor laws. We would all rather be fighting for than against something.

The reality, however, is that opposing unjust and cruel practices is simply part of standing up for deeper positive principles and values which benefit our fellow citizens but which are being violated by these unjust practices. If we truly stand for something, we have no choice but also to oppose that which violates what we stand for. . . .

It would be a worthwhile exercise for all of us to examine the practices or policies we oppose, and to identify the deeper positive principles and truths which lie behind them and which are violated by them. Once we have identified these underlying principles, our efforts can be aimed, with greater precision and gusto, at upholding and celebrating them. Why not laugh, or at least smile, as we do so?

4. Arguments have their limitations

We dare not miss the fourth lesson from Wilberforce since it directly impacts how effective we are in making our case to the world. We have probably all had the experience of watching someone laugh off a particular argument or line of reasoning we found to be downright persuasive with the simple comment, “I just don’t find that convincing.” . . .

This reality about argumentation is sometimes forgotten, but not by Wilberforce. He appeared to recognize more than most that the soundness of an argument or point of view is no guarantee that either will win the day. Far from it. The presence of child labour and slavery were ample evidence of that. Others had argued against them, all without success.

What then did he do? His goal was not simply to give gripping or entertaining speeches. It was to convince his fellow citizens to change entrenched national social and economic policies from which they were reaping enormous benefits, goals which many would, undoubtedly, have considered unrealistic at the best of times.

Did he concede that arguments have limited power and give up on them altogether? Quite the opposite. In Wilberforce’s mind, arguments had to be made again and again, in different ways and through different means, in the House of Commons and outside it, to the elites of society and to the masses, through speeches and through pamphlets. He used every means he could, and in the end his message prevailed. . . .

5. Social justice: an incremental process

The fifth lesson to learn from William Wilberforce may be the hardest of all for some people. It is that achieving social justice is a slow and incremental process. The often plodding, step-by-step nature of Wilberforce’s strategy comes as a bitter pill to some social activists today.

In their zeal to achieve a specific goal, whether banning abortion on demand, eliminating poverty or improving labour laws, some today operate with an ‘all or nothing’ mentality. Anything less than accomplishing one’s full goal all at once is viewed as an unacceptable compromise, as giving tacit approval to an unjust practice.

Not Wilberforce. Though his ultimate goal was clearly to abolish slavery in the British Empire, it quickly became clear that immediate emancipation was neither possible nor practical. He began to realize the power of incremental progress.[6]

If the slave trade could be done away with, he reasoned, the cruelties of the trade itself would end and the supply of slaves would be cut off. It was hoped this would force slave owners to treat their present slaves better because they would be irreplaceable. So for a time he moved to end the slave trade.[7]

At one point he supported a one-year experimental bill, introduced by a friend, to regulate the number of slaves who could be transported on each ship.[8] Often the ships used were not designed for human cargoes and as many slaves as possible were crammed in.

In one instance, 340 slaves out of a cargo of 540 died on a short voyage.[9] If slavery could not be stopped immediately, at least slaves could be treated more humanely while it lasted. The bill passed when MPs visited a slave ship for themselves and saw the inhumane conditions in which slaves were transported.

At another time Wilberforce voted for a bill (The Registry of Slaves Bill) requiring plantation owners to register all slaves kept in each island. His thinking was that once the exact number of slaves lay on record no slave owner could add to his gangs from blacks smuggled in by slave traders defying the abolition laws. Thus a register would stifle smuggling, force owners to treat their slaves properly, thus preparing them to become a “free peasantry.”[10] On a different occasion, an order was given limiting the whipping of slaves.

The value of achieving incremental success was at least twofold: First, even if slavery was never to be abolished, at least life would become more tolerable for slaves. Second, and more powerfully, once Wilberforce’s opponents had voted for better treatment for slaves, they had implicitly stepped onto the slippery slope that could end only in total abolition.

If it was good to limit the whipping of slaves or to create more humane conditions for them on the ships, it must be because they had more worth and dignity than animals. If they did not, then why vote for these more humane conditions? But if the slaves did have more worth than animals, how could supporters of the slave trade continue to condone slavery at all?

By voting for certain bills, Wilberforce’s opponents had tacitly agreed to certain principles that Wilberforce could then use to argue for still better treatment of slaves, and ultimately for abolition. These incremental successes had provided the basis for ending the slave trade.[11] . . .

Obviously, Wilberforce would have preferred an outright ban on slavery to policies that merely made life better for slaves, but a ban was not possible at that time and, therefore, was not a real option for him to consider.

When it came to voting for or against improved conditions on the slave ships, the real choice before him was between slavery with inhumane transport conditions and slavery with somewhat improved conditions.

And we have to ask, given those two genuine options, what principle is there that would require we vote for the former, especially when voting for the latter would also have the additional benefit of creating the basis for future arguments against the institution of slavery itself.

Gifts to the world

The lives of William Wilberforce and others like him have been a profound benefit to the world. We are different because they were here.

These social activists were paragons of perseverance in the struggle for justice, not for themselves but for others. They fought for what they knew was right and were not deterred by opposition. They developed strategies for change and, at all times, were guided by unshakeable moral truths. At the end of the day they mastered the art of engaging the people of their culture and persuading them to change course.

One thing is clear: opposition will always exist for anyone, any time, who takes up the call to impact his culture morally and socially. One lesson, however, rings loud and clear: individuals can and have made real differences in our world.

[2] Pollock, 143.

[3]Lean, p. 49-51

[4] Ibid.

[5] Lean, 53.

[6] For a discussion on Wilberforce’s use of an incremental strategy, see Pollock, pp. 142 ff and Garth Lean, pp. 49-61.

[7] Lean, 49-50.

[8] Pollock, 144.

[9] Pollock, 251-252.

[10] Pollock, 249-250.

[11] Pollock, 87-89.