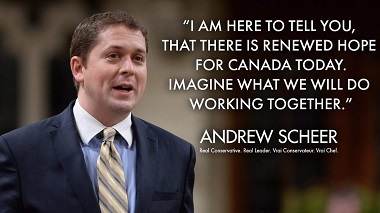

Newly elected Conservative Party leader Andrew Scheer is optimistic about the future.

Possibly Andrew Scheer hasn’t read The Benedict Option yet. He’s in the book’s target group – conservative and Christian – but he’s clearly more disposed to stay and fight the good fight in the public square than is author Rod Dreher. (Scheer is Catholic; Dreher has said he was writing “to all orthodox Christians of good will.”)

The Benedict Option proposes that we “embrace exile from mainstream culture and construct a resilient counterculture,” while Scheer, elected May 27 as leader of the Conservative Party of Canada, appears to be optimistic that he can make changes as the leader of one of Canada’s major political parties.

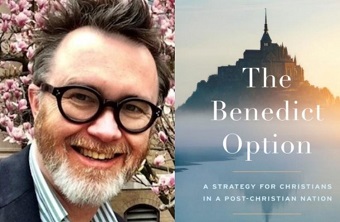

The Benedict Option

The Benedict Option presents Christians with a beguiling strategy in confusing times. Conservative writer/editor Dreher has generated widespread reaction with his new book. Though he is writing mainly for an American audience, his words strike a chord north of the border as well.

The Benedict Option presents Christians with a beguiling strategy in confusing times. Conservative writer/editor Dreher has generated widespread reaction with his new book. Though he is writing mainly for an American audience, his words strike a chord north of the border as well.

Dreher – who joined the Catholic Church as a young man, then became Orthodox about a decade ago – paints a dark picture:

American Christians are going to have to come to terms with the brute fact that we live in a secular culture, one in which our beliefs make increasingly little sense. We speak a language that the world more and more either cannot hear or finds offensive to its ears.

I found myself nodding my head in agreement as I read through the introduction. (It didn’t hurt that on page 2 he referred to his 2006 book Crunchy Cons: The New Conservative Counterculture and its Return to Roots – reminding me of a Vancouver Sun article Douglas Todd wrote about my wife and me as local examples of crunchy cons.)

Dreher referred to the influence of philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, “who declared that Western culture had lost its moorings”:

The time was coming, said MacIntyre, when men and women of virtue would understand that continued full participation in mainstream society was not possible for those who wanted to live a life of traditional virtue. These people would find new ways to live in community, he said, just as Saint Benedict, the sixth century father of Western monasticism responded to the collapse of Roman civilization by founding a monastic order.

I called the strategic withdrawal prophesied by MacIntyre ‘the Benedict Option.’ The idea is that serious Christian conservatives could no longer live business-as-usual lives in America, that we have to develop creative, communal solutions to help us hold on to our faith and our values in a world growing ever more hostile to them. We would have to choose to make a decisive leap into a truly countercultural way of living Christianity, or we would doom our children and our children’s children to assimilation.

Dreher said elsewhere that he used MacIntyre’s thoughts “as a jumping-off point for speculation of my own.”

Reaction to Scheer

The media response to Scheer’s election can’t help but remind one of Dreher’s warnings (keeping in mind that The Benedict Option “does not offer a political agenda”).

The media response to Scheer’s election can’t help but remind one of Dreher’s warnings (keeping in mind that The Benedict Option “does not offer a political agenda”).

CBC opinion columnist Neil Macdonald was not alone in his opinions when he wrote his May 30 column: Andrew Scheer says he won’t impose his religious views on Canadians: We’ll see. Here is a portion:

To be clear here, I am all for a person’s right to believe in whatever he or she desires, to embrace foundational myths of aliens, or miracles, or extreme positions of love or hatred, as long as it remains in a place of worship, with the door closed.

But it usually doesn’t.

Religion most often involves a deep commitment to telling other people how to live their lives. In the U.S. – and to a lesser extent Canada – evangelical conservatives, both Roman Catholic and Protestant, are often a relentless and formidable political force.

Many expect and obtain supplication from candidates for public office. They push for laws that amount to moral dictation, often using their tax-free status to amass funding for their activism. . . .

Tommy Douglas began as a Baptist pastor.

Which brings us to the new leader of the Conservative Party of Canada, Andrew Scheer, who, if the preponderance of political analysis is correct, was pushed over the top by social and religious conservatives. . . .

A couple of things come to mind immediately: 1) Apparently Macdonald is normally a balanced and perceptive commentator. 2) Tommy Douglas – often described as the father of our Medicare and voted The Greatest Canadian a few years ago (on a CBC television show!) – was a Baptist pastor before sticking his nose into politics.

A timely book

Dreher has written about the Benedict Option over the past decade, but it is only with his new book that the concept gained traction. This spring there have been responses from all over the Christian blogosphere, but also serious reviews and articles in secular journals such as The Atlantic, The Spectator and The New York Times.

Appreciation has come from some – at first blush – unlikely sources, such as Russell Moore, president of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, who said:

Appreciation has come from some – at first blush – unlikely sources, such as Russell Moore, president of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, who said:

Rod Dreher is brilliant, prophetic and wise. Even if you don’t agree with everything in this book there are warnings here to heed and habits here to practice.

But there has also been plenty of dissent.

New York Times columnist – and fellow conservative – David Brooks said:

Rod is pre-emptively surrendering when in fact some practical accommodation is entirely possible. Most Americans are not hellbent on destroying religious institutions. If anything they are spiritually hungry and open to religious conversation. It should be possible to find a workable accommodation between LGBT rights and religious liberty, especially since Orthodox Jews and Christians aren’t trying to impose their views on others, merely preserve a space for their witness to a transcendent reality.

My big problem with Rod is that he answers secular purism with religious purism. By retreating to neat homogeneous monocultures, most separatists will end up doing what all self-segregationists do, fostering narrowness, prejudice and moral arrogance. They will close off the dynamic creativity of a living faith.

Political wasteland

Angus Reid made a pertinent comment during a recent lecture on his ‘Spectrum of Spirituality’ polling results:

[The religiously committed – about 20 percent of the population] tend to be socially conservative on many moral issues but tend to swing left on many economic issues.

That doesn’t describe any of the political parties available to us, either provincially or federally. Nor, unfortunately, does it describe Andrew Scheer, who admires Stephen Harper’s fiscal record.

The federal Conservatives have been home to a fairly solid group of social conservatives, but Harper kept them under tight control and Rona Ambrose sidelined them even further as interim leader. They did make a fairly strong showing during the leadership race, so that may give Scheer some breathing room. But many in his own party, let alone the rest of the nation, oppose that approach. (Scheer has said he won’t reopen debates on ‘divisive issues’ like abortion and same-sex marriage.)

In the last federal election, the Liberals wouldn’t allow candidates (apart from incumbents) to run on their ticket if they were pro-life. Many commentators took note of Justin Trudeau’s effrontery, during his May 29 meeting with Pope Francis, in calling for the pope to apologize for residential schools while his party promotes pro-choice, same-sex marriage and pro-euthanasia policies directly opposed to his claimed Catholic faith.

As for the NDP, let’s just say it isn’t the party that Tommy Douglas led. And closer to home, though politics remain interesting in BC, there is no comfortable home for social conservatives with a social conscience.

In the United States, of course, the Religious Right has ended up with Donald Trump.

Dreher rightly says:

The culture war as we knew it is over. The so-called values voters – social and religious conservatives – have been defeated and are being swept to the political margins. . . .

Though Donald Trump won the presidency in part with the strong support of Catholics and Evangelicals, the idea that someone as robustly vulgar, fiercely combative and morally compromised as Trump will be an avatar for the restoration of Christian morality and social unity is beyond delusional. He is not a solution to the problem of America’s cultural decline, but a symptom of it.

So, does it make sense to retreat? “When the foundations are destroyed, what can the righteous do?” (Psalm 11:3)

Guiding principles

Though The Benedict Option is not primarily concerned with politics, Dreher does offer an important caution about the parlous state of political culture. On a positive note – and in a form that applies equally well in Canada – he quotes several guiding principles from Lance Kinzer, a former Republican politician who has retreated from politics, though not completely:

- Get active at the state [provincial] and local level, engaging lawmakers with personal letters (not cut-and-paste mailings from activist groups) and face-to-face meetings.

- Focus on prudent, achievable goals. Don’t fight the entire culture war or waste scant political capital on meaningless or needlessly inflammatory gestures.

- Nothing matters more than guarding the freedom of Christian institutions to nurture future generations in the faith. Given our political weakness, other objectives have to take a back seat.

- Reach out to local media and invite coverage of the religious side in particular religious liberty controversies.

- Stay polite and respectful. Don’t validate opponents’ claims that ‘religious liberty’ is nothing more than an excuse for bigotry.

- Because Christians need all the friends we can get, form partnerships with leaders across denominations and from non-Christian religions. And extend a hand of friendship to gays and lesbians who disagree with us but will stand up for our First Amendment [Charter] right to be wrong.

Dreher endorsed these principles because Christians “cannot afford to disengage from politics completely. The religious liberty stakes are far too high.”

Best wishes Andrew Scheer

National Post reporter Maura Forrest wrote immediately after Scheer was chosen to lead the Conservative Party:

Perhaps Scheer’s most notable policy to date has been his pledge that universities won’t receive federal funding if they don’t defend free speech, a response to recent incidents like the cancellation of a pro-life group’s event at Wilfrid Laurier University.

Scheer would probably find much to commend in Dreher’s book, and he would particularly support him on the importance of religious freedom. He will need that focus, in the face of critics like Neil Macdonald who will only tolerate religion as long as it remains in a place of worship, with the door closed.

Dreher followed up on the six guiding principles with this caution, which would be a helpful reminder for any Christian involved, however indirectly, in the political process:

As important as religious liberty is, though, Christians cannot forget that religious liberty is not an end in itself but a means to the end of living as Christians in full. . . . If protecting religious liberty requires us to compromise the moral beliefs that define us as Christians, then any victories we achieve will be hollow. The church’s mission on earth is not political success but fidelity.

Faithful Presence

Some critics say The Benedict Option is unduly alarmist. I agree with them to the extent Dreher is suggesting we should take time out to regroup and strengthen ourselves – as some of his language seems to suggest. But that’s not the full gospel, and we can’t be sure it would be effective. (I’m looking forward to reading David Fitch’s Faithful Presence, which “embraces the call to reimagine the church as the living embodiment of Christ, dwelling in and reflecting God’s faithful presence to a world that desperately needs more of it.”)

Dreher does envision some ongoing participation in culture and politics, as enumerated in the six principles. He also says:

To be sure, Christians cannot afford to vacate the public square entirely. The church must not shrink from its responsibility to pray for political leaders and to speak prophetically to them.

And even urges a broader vision:

Christian concern does not end with fighting abortion and with protecting religious liberty and the traditional family. . . . Conservative Christians can and should continue working with liberals to combat sex trafficking, poverty, AIDS and the like.

The real question facing us is not whether to quit politics entirely, but how to exercise political power prudently, especially in an unstable political culture.

I hope Scheer – and other Christian politicians – read The Benedict Option, not because it Dreher has everything right, but because he offers a salutary warning about harbouring undue optimism or making unwarranted compromises in this darkening culture.

Other responses

I have barely scratched the surface of The Benedict Option. I do recommend reading the book, but first check out a few of the excellent responses out there:

- David Fitch: The Gospel of Rod Dreher: Why the Benedict Option Needs St. Patrick

- Sam Rocha (lives in Vancouver): The Benedict Option: A Critical Review

- James K.A. Smith in Comment): The Benedict Option or the Augustinian call

- Joshua Rothman (in The New Yorker): Rod Dreher’s Monastic Vision

- Andy Crouch: The Benedict Option in Percentages

There are dozens more, but I found these helpful and they all give a sense of the cultural significance of The Benedict Option. Dreher’s lively and combative responses to Smith and Rocha are amusing – and cause one to hesitate before proffering any opinion about his book.

Hi Flyn

Thank you for that thought-provoking report.

Regarding Scheer, I have never seen so many knee-jerk reactions, from both left and right, about a man who is virtually unknown. Every new leader deserves a honeymoon phase . . . of at least a day or two.

Regarding the endless and complex friction between religion and politics in contemporary society, I rather like “Guiding Principle #3 – ‘nurturing future generations in the faith.'” Christians can’t expect to win political arguments on the basis of political reasoning alone. Before we can be pro-life, we have to be convinced of the sanctity of life. Or in other words, the holiness of the gift of life. So Christians need to shore up the foundations of our own faith communities, promote Biblical literacy and share the joy.

A retreat to monasticism will not, of course, be on the agenda for most of us but I am sure there are things we can learn from our friends in these communities.