Mayor Gregor Robertson (centre) met with faith leaders at Vancouver City Hall November 16.

Last week, for the fourth time since first being elected in 2008, Mayor Gregor Robertson convened a meeting with faith leaders at Vancouver City Hall, to seek their assistance in addressing homelessness and affordable housing. Nearly two dozen senior clergy and nonprofit executives attended, representing Christian, Jewish, Muslim and Sikh communities.

The meeting was called on short notice and had an air of urgency. Winter has arrived early and is forecast to be worse than usual due to La Niña. Homeless numbers have increased since last year. But the good news is that all three levels of government have ambitious immediate plans (and budgets) to create new housing. The question Robertson wanted to ask is, where do faith communities see a role for themselves?

Homelessness on the rise

To provide context for the discussion, Robertson had the General Manager of Community Services, Kathleen Llewellyn-Thomas (who happens to be a practicing Christian) give an overview of homelessness statistics as well as plans to create warming centres, 300 shelter beds and 600 temporary modular housing units this winter.

To provide context for the discussion, Robertson had the General Manager of Community Services, Kathleen Llewellyn-Thomas (who happens to be a practicing Christian) give an overview of homelessness statistics as well as plans to create warming centres, 300 shelter beds and 600 temporary modular housing units this winter.

The latest annual municipal homeless count (March 8) found 2,138 people without fixed address – of whom 537 were unsheltered and 1,601 were in shelters, hospital, detox or city jail. This is 291 more than were found last year and the largest number found in Vancouver to date. (Even so, it should be noted that homelessness is growing much faster in the suburbs.)

City staff are particularly concerned that more and more seniors are homeless each year and that Indigenous people are vastly over-represented. Whereas about two percent of the general population identify as Indigenous, 39 percent of Vancouver’s homeless population do.

More alarming still is the fact that 66 percent of unsheltered homeless women are Indigenous. First Nations women are the most vulnerable of the most vulnerable.

Nevertheless, Llewellyn-Thomas reminded us, men account for 76 percent of the homeless in Vancouver. Most of these men are middle-aged. If in our eagerness to help other populations we fail to design housing and supports for this largest group, then we will never end homelessness.

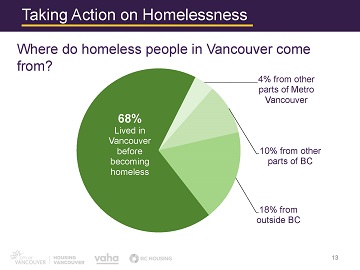

She also emphasized that about 20 percent of homeless people are employed part- or full-time, that 42 percent are homeless for the first time, and that 68 percent lived in Vancouver before becoming homeless.

Temporary modular housing

In its September budget update, the newly formed NDP provincial government announced it was allocating $291 million to create 2,000 units of temporary modular housing across the province over the next two years, and an additional $172 million to operate them over three years.

Vancouver is receiving 600 of these modular units because, based on the 10-year average annual increase in homelessness, that is how many people are projected to be unsheltered next year if nothing new is done. Mayor Robertson has set a very ambitious goal of having all 600 units built and occupied before winter ends.

Temporary modular housing has numerous advantages. Built in factories, the cost-effective self-contained units can be constructed and installed in two to four months, reducing waste during manufacturing and minimizing impacts of construction on the surrounding community. With a useful life of about 40 years, they can be re-configured and relocated to fit different sites and local needs, while permanent housing is being built.

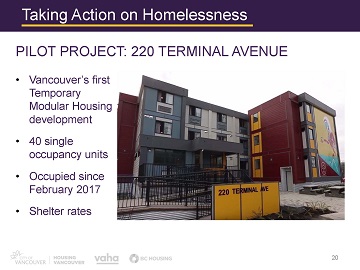

In February the city opened a pilot project of 40 modular units at 220 Terminal Avenue. My office is nearby and I have a background in construction, so I was amazed to watch how quickly the three-storey complex took shape. Tenants of the building as well as neighbouring businesses testify to the project’s positive impact.

Can your church help?

Building on that success, the city is seeking a dozen or so sites that can accommodate 50 to 100 units each (there are approximately 50 units per building). Studio units will be 250-350 square feet in size and have private bathrooms and kitchens. Ten percent will be wheelchair accessible on the ground floor.

In addition to the expected security measures and onsite 24/7 support services staffed by experienced nonprofits, BC Housing has funded amenity spaces in most buildings – notably, communal kitchen and dining areas.

Buildings will be distributed across neighbourhoods with the greatest need, on vacant or underused sites accessible to transit and health services. While there are potential city-owned sites, most are likely to be leased from other partners willing to extend a nominal cost five-year lease with an option to renew for another five years.

Practical issues

Obviously, Mayor Robertson and city staff are eager for faith communities to offer use of their parking lots or other spaces. On the one hand, this is exactly the kind of open-handed hospitality Jesus asks us to offer. On the other hand, I’m confident there are far fewer suitable church properties than the city thinks there are.

The vast majority of congregations do not have a parking lot or green space, or have a small one, or are fully using it. One pastor also privately voiced concern about what would happen when the lease ends if not enough permanent housing had been built yet: will churches be pressured to indefinitely host “temporary” units?

On that note, the federal government has pledged $40 billion to construct 100,000 new social housing units, and renovate another 300,000 existing ones, over the next decade.

I believe the temporary modular units are a brilliant addition to the continuum of housing that needs to be strengthened in our region. I recall brainstorming just this sort of thing with Judy Graves, the city’s now retired Homelessness Outreach Advocate, seven years ago.

Ways to contribute

The city suggested several ways for faith groups to participate.

Even if your congregations can’t host a modular building, there are vital ways you can contribute to their success. Speak out in support of the initiative generally. If a site is proposed in your neighbourhood, work with everyone affected to forge community-based solutions to fears and concerns. Organize practical expressions of welcome toward the new residents. Seek ways to be neighbourly with them.

Perhaps the best way to begin is to take advantage of the commercial kitchens and dining areas being designed into the buildings. Nonprofits such as CityGate Leadership Forum, Union Gospel Mission and SoulKitchen can guide you in facilitating inexpensive resident-led meal programs that establish mutually-enriching friendships. I’ve seen firsthand the profound difference such programs make in the atmosphere at social housing complexes and in the lives of residents and volunteers alike.

Emergency shelters

Mayor Robertson is also asking faith communities to operate Emergency Weather Shelter beds (with funding from BC Housing) or “warming centres.” These warming centres don’t allow guests to sleep overnight, but offer respite from the weather when temperatures reach -5°C. They won’t operate more than five days in a row and will alternate with other sites where possible to provide continuity of service. Although host organizations will be responsible for operating the warming centres, the city will cover all costs and offer training.

If you would like to learn more or get involved email [email protected].

Jonathan Bird is executive director of CityGate Leadership Forum, which “assists churches, charities and change-makers to work with the poor for the holistic well-being of the people and places of metro Vancouver.”