“Every inch of soil beneath my feet was red, shining under the frail winter sun, as if it had been soaked in blood.” (Liao Yiwu, while trekking a narrow mountain path in Yunnan.)

“Every inch of soil beneath my feet was red, shining under the frail winter sun, as if it had been soaked in blood.” (Liao Yiwu, while trekking a narrow mountain path in Yunnan.)

God is Red is a collection of 18 loosely linked interviews and essays exploring the ways in which spirituality – Christianity in particular – is thriving in post-Mao China, in the face of widespread corruption and the loss of faith in Communism. The book exemplifies Liao Yiwu’s concern for those on the margins of society.

Life in a Chinese prison

Liao wrote his epic poem ‘Massacre’ in the wake of China’s bloody crackdown on student protests in Tiananmen Square in 1989, then spent the next four years in prison for his literary boldness.

A friend of the renowned human rights activist Liu Xiaobo, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize while in jail in 2010, Liao has begun to enjoy some celebrity around the world as well.

Sometimes likened to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn – who so eloquently made the world aware of the Soviet prison camp system in The Gulag Archipelago – Liao’s status has been confirmed with his just-published account of life in a Chinese jail. For a Song and a Hundred Songs: A Poet’s Journey Through a Chinese Prison was described in the New York Times as “a compelling and harrowing read.”

Sometimes likened to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn – who so eloquently made the world aware of the Soviet prison camp system in The Gulag Archipelago – Liao’s status has been confirmed with his just-published account of life in a Chinese jail. For a Song and a Hundred Songs: A Poet’s Journey Through a Chinese Prison was described in the New York Times as “a compelling and harrowing read.”

Meeting Dr. Sun

God is Red is based on Liao’s experiences in Yunnan, a province in the far southwest of China. Liao had jumped from his second floor apartment to escape public security agents who had come to interrogate him. “I fled to the sun-drenched city of Dali . . . Broke and depressed in a new city . . . I roamed the streets, hanging out with beggars, street vendors, musicians and prostitutes, listening to their life stories. In the evenings, I doused my loneliness with liquor . . .”

It was in this frame of mind that Liao met Dr. Sun in 2004. Sun had quit his position as dean of a large medical school near Shanghai to heal the sick and spread the gospel in Yunnan. Liao was intrigued; he had earlier come to know a few Christians and admired their courage, even though he didn’t – and still doesn’t – share their faith. When Liao asked if he could interview Sun, he said he’d lived an ordinary life and suggested instead that he accompany him to the mountains to hear some “extraordinary stories in the villages there.”

A year later Liao went on a month-long journey with Dr. Sun. He was reminded of the old Chinese saying: ‘Heaven is high above and the emperor is far away,” and wondered “how it was possible for Christianity, a foreign faith, to find its way and grow in such isolated locations.”

China Inland Mission

Local people told him that the China Inland Mission had sent missionaries to Shanghai 150 years ago, and that they had quickly travelled to the furthest corners of China. “These foreigners, ‘with blond hair and big noses,’ [arrived] . . . just in time to save the people from a bubonic epidemic.” Liao, who had grown up in an era when missionaries were portrayed as ‘evil agents of the imperialists,’ was surprised by such stories.

“Three or four generations later,” Liao said, “Christianity was part of the heritage of each individual family and an integral part of local history . . . in the Yi and Miao villages, Christianity is now as indigenous as qiaoba, a special Yi buckwheat cake.”

But at a great price. “The circuitous mountain path in Yunnan province is red because over many years it has been soaked in blood.” His appreciation of the missionaries and his interviews with old pastors, nuns and lay people, in which their long-suffering hope for the future is so apparent, lie at the heart of this moving book.

Dedicated missionaries

“I was struck by the dedication of the missionaries,” Liao says. Jessie McDonald (born in Vancouver) arrived in China in 1913, and worked at a hospital in Kaifeng. When the Japanese took over that city, she moved the hospital to Dali, in Yunnan. She carried on until Communist officials seized the hospital and forced her out of China in 1951.

Liao bears witness to McDonald’s life of sacrifice – and that would be reason enough to justify reading God is Red. But the width of his vision and his eye for telling detail set this book apart. During his reflections on McDonald, for example, he quotes aptly from the French poet Paul Valery.

McDonald is said to have been the last missionary to leave China.

“On her last day,” Liao writes, “she ignored the threats of soldiers and went to pray at what is now the Old City Protestant Church built by missionaries in 1905. She was alone in the church surrounded by empty pews . . . McDonald made for the bell and struck it for the last time. The sound rippled through the city. Three old men drinking tea in the old city remember it. ‘The chiming came in waves, resounding waves, one after another; people in Xiaguan could feel the vibration,’ said one.”

Persevering believers

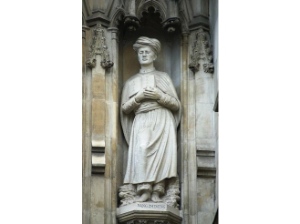

One of Liao’s interviews was with Wang Zisheng, the son of Wang Zhiming, who was arrested in 1969 and executed in 1973 after serving the Miao people for many years.

One of Liao’s interviews was with Wang Zisheng, the son of Wang Zhiming, who was arrested in 1969 and executed in 1973 after serving the Miao people for many years.

His martyrdom was commemorated in 1998 by a statue – one of 10 recognizing martyrs from around the world – above the Great West Door to Westminster Abbey in London.

There are many stories of persecution in this book; Wang Zhiming is unique only in having been chosen for notice by the outside world. Liao is helping to redress this imbalance.

Ironically, Wang Zisheng only learned about the honour paid to his father after the fact, and first saw pictures of the statue in 2002. “We all cried when we saw them,” he said. “My father had fought against devils in those dark days and had triumphed.” Did he feel bitter about the past? “No, I don’t feel bitter. As Christians, we forgive the sinner and move on to the future. We are grateful for what we have today.”

Among the things they have today is a dramatically larger church, grown from less than 3,000 when his father was preaching to some 30,000 now. (The church in China numbers between 50 and 100 million now, up from well under 5 million when the Communists took over.)

Heroic Christians

Following a return trip to Yunnan in 2009, Liao commented: “These trips have exhilarated me, lifting me out of my drunken depression. The stories of heroic Christians . . . inspired me, prompting me to write a book [about] a new Christian identity that is distinctively Chinese.”

Historian Philip Jenkins says, “It is very difficult to read Liao Yiwu’s work without being constantly reminded of Christian struggles in the ancient Roman Empire, where a harassed minority was struggling to exist . . . Who can tell how the story will play out this time round?”

The situation may be improving. Open Doors ranks nations according to how much persecution Christians suffer. This year China came 37th (moderate), down from 21st (severe) in 2012. Not committing itself too far, Open Doors makes this succinct comment: “Four issues get the church into trouble: when they are perceived as too powerful, too political, too foreign or a cult. For the foreseeable future, the new government is likely to use religion rather than exterminate it.”

God is Red and For a Song and a Hundred Songs make it clear that Liao, for his part, believes that the Christian community is not foreign and it is a good influence – and that he will remain committed to providing a voice for the voiceless.