Queen Mary Agnes Capilano waited in vain to meet with the British royal couple. (C.P. Detloff or W.B. Shelly, City of Vancouver Archives AM73-S1-1—: CVA 6-108)

In Allan Twigg’s book Aboriginality, he tells of a meeting between three sovereigns – a king and two queens – that never happened. It was missed by inches. The year was 1939. The place, Vancouver. The occasion, England’s King George VI and Queen Elizabeth’s visit to Canada.

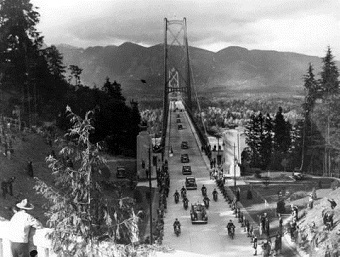

A year earlier, the Lion’s Gate Bridge, joining Stanley Park to West Vancouver, had opened. The King and Queen and their entourage were to drive over the bridge to “honour it.” The lands needed to build the bridge had been transferred in 1936 from Indian Reserve lands to the First Narrows Bridge Company “without consultation and little compensation.”

But the Squamish people, at least, bore no ill-will. Instead, they officially requested a meeting between their Queen, Mary Agnes, and the English royals. The Squamish wished to exchange gifts and greetings. Queen Mary dressed for the occasion in full ceremonial regalia. Alongside her was her son, Chief Joe Mathias, who had actually sailed to England in 1911 to attend the coronation of King George.

King George VI and Queen Elizabeth did not stop to meet Queen Mary Agnes. (City of Vancouver Archives AM73-S1-1—: CVA 6-104 )

Here’s what happened: “The royals didn’t stop. Nobody from the Squamish Band was invited to take part in the honouring ceremony. ‘This was the only time we could present my grandmother to the Queen,’ recalled Chief Simon Baker, ‘but the car drove past us. . . . It was terrible for my grandmother.’”

Later, the Honorary Secretary of the Vancouver Committee for the Reception of Their Majesties sent a letter to the Squamish people. Besides assuring the Squamish people that their gifts had been received and sent to Buckingham Palace, it contained an explanation about the matter of the drive-by:

“We can assure you that every effort was made to fulfill the wishes of Their Majesties and had they desired to stop, it would have, of course, been done. We are assured that the Majesties took particular pains to acknowledge the homage of their Indian subjects, and that in passing them the rate of speed was considerably lowered.”

In passing them the rate of speed was considerably lowered. A line like that, so cavalier, so breezy, so condescending, reflects the ethos of an epoch. In 1939, attitudes of official racism were everywhere – fascism in many European nations, anti-Semitism in most, Jim Crow in the American south, apartheid in South Africa. 1942 would see the beginning of the roundup, property-confiscation, and internment of Japanese Canadians. These are only a few of the better-known examples of attitudes, assumptions and actions pervading the air everyone breathed.

And then there were Canada’s First Nations people. We had begun to organize official prejudice toward Native peoples many decades earlier, in the late 1800s.

It was embodied in the growing presence of Indian Residential Schools across the land. It was reflected and made into legal code in the ever-expanding reach of the federal Indian Act. It was expressed in government appropriation of Native lands and retraction of Native resource rights, and in the legal pettifogging and stonewalling over treaty settlements.

A history that began, largely, full of mutual honour and promise was swiftly becoming rife with betrayal and resentment. White Canadians are heirs of all this. We’re beneficiaries.

I know most of us are not directly implicated in any of it. We are, after all, innocent of any personal wrongdoing. We didn’t draft or enforce the oppressive measures of the Indian Act. We didn’t remove Native children from their families and communities and abuse them, verbally, emotionally, physically, sexually, in Residential Schools. We didn’t start the fire.

But the majority of white Canadians grew up in a culture and an economy that, at least in part, has been built on the backs of the land’s first inhabitants. We may not have committed any overt acts of injustice, but most of us have been beneficiaries of, and bystanders to, such acts.

Our forebearers took much from the people, and didn’t say thanks, and didn’t say sorry, and rarely looked back. And we, for the most part, have been happy to reap the windfall, or at least remain uninformed and uninvolved. And many of us still carry, dormant perhaps but ready to awake with little stimulation, the very racism that marked out our forbearers.

Why would I make such a bold and sweeping indictment? Because most of us are still just driving by, and often not even at reduced speed.

My journey

That was me for most of my life. And then it got personal. In 1995, I moved to Duncan, a small community on Vancouver Island, and stayed 18 years. Everywhere I had lived before made it easy to avoid First Nations people, and therefore easy to avoid my real attitude toward the people. In every other place I lived, the Native reserve was at a distance from the municipality. I rarely saw a real live Indian.

That changed when I moved to Duncan. The reserve, geographically and demographically, intersects the municipality at several points. The two are woven together tight as a wampum belt. Many of the area’s place names – Mount Tzouhalem, Penelekut Island, Sansum Narrows, Cowichan River – reflect this. Duncan is 1/8th First Nation, and that percentage of population is visible everywhere. Native people are impossible to ignore or avoid. I managed it anyhow for almost a decade.

The church I pastored met on Tzouhalem Road, named after a 19th century hereditary chief. Across from our church building stood – until it burned down in 2010 – the old offices for the Cowichan Band. If I turned left from the church parking lot, I skirted the edge of the reserve and then, about a kilometer down, crossed into reserve lands. I always knew where the boundary line fell, though no sign marked it: the houses told me. Most were dilapidated, with flaking paint, caked on moss, grimy and sometimes broken windows, collapsing stairs. Garbage and rusty cars littered the yards.

Later, I found out why many homes on reserves look this way. There are two main factors.

One is the legal nature of reserve lands, which can never be sold on the open market. The effect of this is that reserve lands never increase in value (unless turned into leased land, but that’s another story). This means that a house on the municipal side of Tzouhalem Road might, over five years, increase in value from $300,000 to $400,000. But a similar house on the reserve side of the road might only be worth $30,000. Forever. Its value never increases, and usually decreases, as does all aging things. This kills all incentive for doing home improvements.

The second reason is that entire extended families live in many of these houses. A house designed to hold, say, five people comfortably might have 10, 15, 20 people living in it at various times. That’s because Native people generally have a deep value for sharing: it’s uncommon for a First Nation’s person with a house to turn away even a distant relative in need of a place to stay. Yet a house built to hold five people can’t handle 10-plus people living in it any more than a car designed to seat five people can handle 10-plus people regularly cramming into it. Things break down much faster.

But I knew none of this at the time. All I saw were dishevelled yards and ill-kept houses and rusting jalopies. And I made a judgment about the people who lived there. The judgment distilled to a single word: typical. Because I had no real relationships with First Nations people – I knew a few to nod at in passing – there was nothing to disturb either my facile judgment or my illusion that I held no prejudices. I just kept driving by.

Eat whatever they put before you

Then I met Tal. Tal James is Penelekut, a band from an island close to Duncan. Tal had, in his early 20s, become a Christian. Today he works with North American Indigenous Ministries, a mission agency dedicated to sharing the gospel – in all its dimensions with First peoples. Tal has become a good friend. He has let me ask, and patiently answered, many stupid questions.

He has taught me much about his culture, and helped me get past my uninformed reactions to Indigenous practices, places, legends, artifacts – powwows, sweet grass ceremonies, totem poles, long houses, wampum, thunderbird stories – things I once knew nothing about, but held opinions and made judgments about anyhow.

And sometimes Tal, along with his German wife Christina, have gently but firmly rebuked me for my subtle but clear racism.

An example will help. Tal and I are at a restaurant in Nanaimo not long after I have announced to the church in Duncan my intention to “reach First Nations people for Christ.” We’ve just ordered lunch. I turn to Tal and ask what many of the people in the church are asking me: “What should we do about the dark side of Native spirituality? Many in the church feel that they cannot have fellowship with a First Nations people before they have figured this out.”

Tal falls silent. He looks around. He leans forward. “Mark,” he says, “why did you come into this restaurant, take a seat, order a meal, without once asking or worrying about the spiritual beliefs and practices of the people who own the restaurant, manage it, or work in it? You’re about to eat food prepared by someone you don’t know but who, more likely than not, does not share your beliefs or morals. You don’t seem the least bothered by that. But you do seem bothered by the idea of sitting and eating with my people unless first you approve of our spirituality – which, by the way, you know little about.”

I was stung. But he was right. And that day began for me a fourfold journey: one, facing my prejudices without illusion or justification; two, forsaking them; three, learning First Nations culture from First Nations people; and four, committing to loving my neighbour as myself. It has been a slow walk, sometimes agonizing, but deeply liberating. I still have a ways to go. But I am thankful that I have made a beginning.

About a year after this conversation with Tal, I was at a meeting with several people who were helping a friend and I plan an event called “Understanding the Nations.” It was to be a five-hour workshop educating churches about local First Nations history and culture, and challenging them to engage in practical acts of reconciliation.

One of the people we’d invited was Dan Marshall. Dan is a university professor who had written a superb history of our local tribe, the Cowichan people. We hoped Dan would present at the workshop on Cowichan history. But he was wary of my motives.

He deeply loved and respected the Cowichans and, as he said, didn’t want to be part of a “new colonial, imperial, paternalistic effort to impose the Christian religion on First Nations people.” Then he asked me outright: “Is your intention with these workshops to try to convert the Cowichans to Christianity?”

God had now, for a year, been excavating me, exposing me, burning things out of me, pounding things into me. I said to Dan (who later became a good friend), “I admit, my dream is mass conversion. I would love to see everyone – all nations, all people of whatever ethnic identity in this community, and you also, Dan – I’d love to see all come to know Jesus Christ. But you are asking about my intention for these workshops. That’s simple: I want to convert the church.”

For two years, we ran the workshops in over 10 venues – mostly churches. Around 1,000 people attended in all. And it happened: though several Cowichans got curious about the church, and some ventured near, and a few put their faith in Christ, the majority of conversions were among white Christians.

More and more of us began to see our entrenched racism, to repent of it, and to begin a journey toward real change. More and more of us chose to no longer just drive by. We slowed. We stopped. We got out of the car. And most of us have never been the same.

Praying with smoke

Ray Aldred is a Cree storyteller and Christian theologian, and a dear friend and colleague. Recently, we both spoke at a church conference on missions. We decided on the final evening of the conference to weave our talks together, back and forth, circling each other’s stories, building off each other’s insights. It was like a tribal dance. Obviously, we had to choreograph it. “I think you should invite me up right at the start,” Ray said. “I will honour the traditional occupants of the land and thank them for allowing us to be here. And then I will pray with smoke.”

Praying with smoke is a Cree tradition (shared by many Plains Tribes) of burning sage or sweet grass (the fragrance of which bears an unnerving resemblance to cannabis) in an abalone shell, snuffing out the fire, and wafting the smoke, with an eagle feather, until its fragrance pervades the room, all the while inviting the Spirit to come from all four corners of the earth and, like the fragrance, fill the room.

“Um, ok. You know people will freak out?”

“I know.”

“I’m good then. Let’s do it.”

So we did. And people freaked out.

I was up next. “I sense,” I said, “that many, if not most of you, are deeply uncomfortable with what just happened. I’m going to ask you to do something with that: neither reject it nor embrace it. I’m inviting you, instead, to hold it in open, upturned, outstretched hands” – I modelled this as I said it. “And I’m asking that you give both Ray and I an honest hearing.”

That seemed to settle things down, and so Ray and I spoke, back and forth, moving in and out of each other’s space, doing our dance. We talked about the broad sweep of the Canadian church and government relations with First Nations people throughout our shared history.

We talked about the tribal, ceremonial and storytelling roots of biblical faith. We talked about how the church had repeatedly missed opportunities with First peoples to share the full gospel in all its wild, profuse, subversive, scandalizing, extravagant beauty and potency; had failed to incarnate the wide-open arms of God, and yet every once in a while had got it right.”

By the end, I sensed a new readiness and openness among those present. I stood on the platform and held out my open, upheld, outstretched hands.

“Some of you,” I said, “still aren’t sure what to do with what you saw earlier. But I’m sensing that most of us – maybe all – want to be part of a new story. We’ve heard enough of the old story to feel some appropriate guilt and shame and heartbreak. But what use in getting stuck there? Let’s resolve to create a different future. I’m not even sure what the next step is, other than it involves a fierce ‘Yes’ to that different future, an unswerving commitment to write a new story. If you want to be part of that, would you stand, and with open, upturned, outstretched hands, say to God, ‘Yes’.”

As far as I could tell, the whole congregation stood.

A year later, Ray was speaking at a chapel service at Ambrose University, where Ray and I are colleagues [until recently; Ray has recently begun teaching at Vancouver School of Theology]. He began by praying with smoke, wafting the smoke with an eagle feather so that the fragrance of the sweet grass pervaded the auditorium.

And then he invited me up. Ray gave me the eagle feather. He said it was his gift to me, to honour my love for, and my work with, First Peoples. I was overwhelmed. And felt unworthy. Really, I haven’t done much. I just stopped driving by.

‘The day I stopped driving by’ first appeared in the Spring 2016 issue of Mosaic Magazine. The story is re-posted by permission of Canadian Baptist Ministries.

Mark Buchanan has written several books (Your God is Too Safe, Hidden in Plain Site) and is associate professor of pastoral theology at Ambrose University.

He will be teaching For the Healing of the Nations at Regent College July 18 – 22, and will also offer a free lecture at the college July 18: Every Tribe & Tongue & Nation: The Church & Canada’s First Nations.

On June 21 Regent College interviewed Buchanan on Working for Reconciliation.

A good article on the truths on how the Squamish Nation was really snubbed. Mary Capilano was the grandmother of my grandfather (Chief Simon Baker).