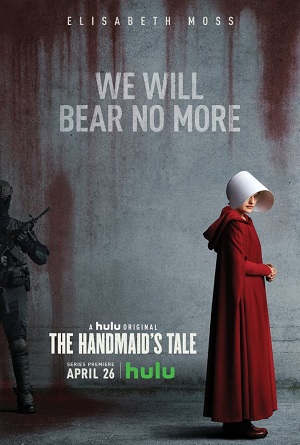

Elisabeth Moss plays Offred in The Handmaid’s Tale. Hulu photo.

Margaret Atwood is one of Canada’s best known personages, but Hulu’s recent TV adaptation of her novel The Handmaid’s Tale has heightened her profile even more.

Response to the dystopian series – which focuses on a young woman forced to live as a concubine under a fundamentalist theocratic dictatorship – has been very positive. Many have referred to the show’s timeliness – an answer to Donald Trump, the Religious Right and all things authoritarian . . . .

The day after Donald Trump was elected President, The Verge ran an article titled ‘In Trump’s America, The Handmaid’s Tale matters more than ever.’ Last month, Vanity Fair ran ‘The Handmaid’s Tale: How a 30-year-old story became 2017’s most vital series.’ And so on.

The Atlantic published an article May 24 responding to this spate of articles. In ‘Don’t overinterpret The Handmaid’s Tale’, Shadi Hamid looked at “what the dystopian series does not imply about the role of religion in politics.” He pointed out some writers are losing perspective:

Some liberals have managed to draw parallels closer to home, which has led to some absurdly mismatched comparisons. The New Republic’s Sarah Jones writes that “Texas is Gilead and Indiana is Gilead and now that Mike Pence is our vice president, the entire country will look more like Gilead, too.” No, Texas is not Gilead; it’s a state where people are peacefully and democratically expressing social conservatism. And as for the nation, Americans did just elect the most secular president perhaps in the country’s history.

During interviews, Atwood herself stresses that The Handmaid’s Tale was published more than 30 years ago. Speaking with Matt Wilstein of The Daily Beast she said she recognizes the renewed relevance of the book, but added that in 2017 it is less “alternative reality” and more of a warning about what might “actually happen” if those who fight for equal rights are not vigilant.

During interviews, Atwood herself stresses that The Handmaid’s Tale was published more than 30 years ago. Speaking with Matt Wilstein of The Daily Beast she said she recognizes the renewed relevance of the book, but added that in 2017 it is less “alternative reality” and more of a warning about what might “actually happen” if those who fight for equal rights are not vigilant.

Reception by the Christian community has, predictably, been quite varied. Writing on the Patheos Catholic site, for example, Mary Pezzulo found it “heavy-handed but artistic.”

S.D. Kelly, in a fairly critical article appearing in Christianity Today, was not convinced by the logic of story:

We are necessarily being asked to see the horrors of The Handmaid’s Tale in light of the ideology of actual fundamentalist Christians and in light of how our society actually treats women.

This, in short, is where The Handmaid’s Tale stumbles.

(It is interesting to note that Sarah Jones, in her rather extreme New Republic comment, says that reading The Handmaid’s Tale was one of two major influences causing her to leave the hermetic world of very conservative Christianity.)

Atwood had a warmer reception in Sojourners, where Layton Williams interviewed her:

Speaking to Sojourners about the nature of the type of theocratic regime she originally envisioned for America in her book, Atwood pointed out that it is not genuinely Christian so much as “purportedly Christian.”

“I don’t consider these people to be Christians because they do not have at the core of their behavior and ideologies what I, in my feeble Canadian way, would consider to be the core of Christianity,” Atwood said, “. . . and that would be not only love your neighbors but love your enemies. That would also be ‘I was sick and you visited me not’ and such and such . . . But they don’t do that either.

“Neither do a lot of the people who fly under the Christian flag today. And that would include also concern for the environment, because you can’t love your neighbor or even your enemy, unless you love your neighbor’s oxygen, food and water. You can’t love your neighbor or your enemy if you’re presuming policies that are going to cause those people to die.”

Meeting ‘God’s Gardeners’

I particularly enjoyed a May 20 article by Peter Robb in ARTSFILE, Ottawa’s online arts and culture journal: Restorying Canada: Margaret Atwood, Leah Kostamo on the yin and yang of utopia and dystopia.

I particularly enjoyed a May 20 article by Peter Robb in ARTSFILE, Ottawa’s online arts and culture journal: Restorying Canada: Margaret Atwood, Leah Kostamo on the yin and yang of utopia and dystopia.

Robb did a good job bringing out the connection between the two women, the centrality of creation care for both of them and more thoughts from Atwood related to Christian faith.

Robb was reporting on an evening presentation by Atwood and Kostamo, who were on a panel at the University of Ottawa, taking part in The Future of Religion in Canada: Utopia or Dystopia (Restorying Canada). He described how that pairing came to be:

Atwood appeared with Leah Kostamo, a BC-based eco-Christian, who with her husband, has founded a branch of the A Rocha movement in her home province, a community that in many ways reminds one of God’s Gardeners, the moral heroes of Atwood’s science fiction trilogy Oryx and Crake, The Year of the Flood and MaddAddam.

Kostamo described what she and her comrades are trying to achieve as stewards of the land they occupy. That is to rebuild the environment, offering her community’s example as a way to rebuild the natural world. “How do we live well so we can repair (the land) and become more sustainable,” she says. . . .

Markku and Leah Kostamo met Margaret Atwood on Lorna Dueck’s Context TV show in the fall of 2013.

[Atwood] began by explaining how she met Kostamo.

“I wrote about a Christian-cum-naturist-cum-ecological group in the near future that lives on urban rooftops and cultivates gardens on them. And they also chose hope and tried to reconcile science and ecology with scripture. Sound familiar?

“Because I had written this group, I was invited to be on a TV show. And Leah and Markku (Kostamo) appeared miraculously from behind the woodwork and there they were, what I had written.”

(For more on how they met go here. Atwood was the featured speaker at A Rocha’s Green Gala three years ago.)

Atwood described three ways of understanding the relationship of humans to the natural world: Rapturists (“God is going fry everybody but them”), Dominionists (“they can destroy any old thing and it doesn’t matter because you’ve got dominion”) and Stewards (“yes they were entrusted with this (world), but their duty is . . . to take care of the garden”). Kostamo and A Rocha are, of course, in the latter group.

She revealed herself to critical of some elements of religion, positive about others. She said, for example:

She revealed herself to critical of some elements of religion, positive about others. She said, for example:

Atheist regimes have done a good job of oppressing and murdering people too. It is true that Christianity has some dark moments. But I don’t think you can put that down to a religion. I think you can put that down to human beings.

And:

The religion in MaddAddam is benevolent but in The Handmaid’s Tale it is not benevolent. It is a totalitarian theocracy. Does that mean I am anti-religion? No. It means people have frequently used religion as a means of controlling societies and of getting rid of people who don’t agree with them. That is just historically true.

Robb noted:

When Atwood wrote The Handmaid’s Tale she says she considered what kind of totalitarian dictatorship could occur in the U.S. She settled on a theocracy after ruling out a Communist state and a liberal democracy that crushes freedom to protect itself. Today, she said, somewhat tongue in cheek, “I may be wrong. We will wait and see. . . . Somebody should tell the American right (the novel) is not a blueprint, but it kind of is.”

For Peter Robb’s full article go here.

For a very good post by two ‘Future of Religion in Canada’ conference participants – I would probably have posted it instead of what I wrote myself, had I known of it sooner – read His Eye is on the Sucker.

A Rocha is holding a Barn Raiser gala today (May 25) at the Vancouver Convention Centre, featuring world-renowned National Geographic wildlife photographer Joel Sartore.

A Rocha is holding a Barn Raiser gala today (May 25) at the Vancouver Convention Centre, featuring world-renowned National Geographic wildlife photographer Joel Sartore.

On a related note, evangelical climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe, another of A Rocha’s guests (at the Chan Centre two years ago), appeared on CBC Radio’s The Sunday Edition with Michael Enright April 30: Donald Trump versus the climate: a conversation with Katharine Hayhoe.