The BC Humanist Association (BCHA) is determined to make our province more secular. Most recently, the group took aim at prayer in the BC Legislative Assembly – and won a small victory, with minimal opposition.

Earlier this fall, the local “voice for humanists, atheists, agnostics and the non-religious” released a 138-page House of Prayers report which analyzed the daily prayers offered in the Legislature between 2003 and 2019.

After noting that “the prayers delivered in the BC Legislature can vary considerably, ranging from sectarian prayers invoking the name of Jesus, to attempts at poetry, to partisan attacks,” the BCHA came up with “three key recommendations”:

1) Abolish the practice of legislative prayer altogether.

2) Replace the practice with a First Nations territorial acknowledgement.

3) Replace the practice with a time for silent reflection.

The end result wasn’t quite as dramatic as the humanists had hoped for, as a November 29 article by Jennifer Saltman in The Vancouver Sun pointed out:

A motion from House Leader Mike Farnworth was passed on the last day of the legislative session, which changes the time for “Prayers” to “Prayers and Reflections.”

The B.C. government will continue to pray before the start of each sitting of the legislature, but it has changed the name of the practice to include non-religious reflections. . . .

Each day that the house sits, at the start of business, an MLA rises in the legislature to deliver a prayer. The person who speaks is welcome to say a prayer from their faith or spiritual belief, or to offer some kind of secular reflection.

Go here for the full article.

The whole affair could be pushed aside as innocuous, but it does raise at least three significant issues:

- (non)engagement of the church

- prayer, just the beginning?

- separation of church and state

(Non)engagement of the church

I had not heard anything about the BC Humanists’ initiative – until I received an update from ARPA Canada, which says its mission “is to educate, equip and encourage Reformed Christians to political action, and to bring a biblical perspective to our civil authorities.”

I had not heard anything about the BC Humanists’ initiative – until I received an update from ARPA Canada, which says its mission “is to educate, equip and encourage Reformed Christians to political action, and to bring a biblical perspective to our civil authorities.”

Levi Minderhoud, ARPA’s BC manager, posted Defending Legislative Prayer in British Columbia, October 22. He wrote:

Knowing that God hears the prayers of His people and knowing that our prayers have the power to benefit even an unbelieving society, I believe the practice of prayer in the Legislature is worth defending. With this in mind, I would like to respond to the two overarching arguments made by the BCHA, that legislative prayer is both discriminatory and exclusionary.

BCHA Argument #1: Legislative prayer is discriminatory because it promotes specific denominations or a specific religion over others. Christianity, in particular, is over-represented.

Rebuttal: The BCHA’s argument that legislative prayer is discriminatory and disproportionately favours Christianity is based on a misrepresentation of the facts. . . .

BCHA Argument #2: Legislative prayer is exclusionary because it excludes non-believers and believers whose faith traditions do not include prayer.

Rebuttal: Let’s clarify what type of exclusion the BCHA claims is happening. No one is excluded from being present in the chamber during the prayer. No one is excluded from offering a prayer for any reason, and non-religious MLAs are welcome to lead their colleagues in a moment of silent reflection or share a secular quote. . . .

Go here for the full comment.

Many Christians would agree that the change adopted by the BC legislature November 28 is not particularly alarming. In fact, it is interesting to note that when Ian Bushfield, executive director of the BCHA, gave his organization a pat on the back for its work on the prayer issue, Liberal MLA Laurie Throness – well known as a Christian – tweeted, and commented on the BCHA site:

The Standing Orders of the BC Legislature were just changed by unanimous consent to read ‘Prayers and Reflections’ at the start of each sitting day instead of ‘Prayers’ alone. Just as I recommended. #bcpoli

The shift may not be serious in itself, but we have likely not heard the end of this issue.

Prayer, just the beginning?

MLAs in the Legislative Assembly of BC easily agreed to change ‘Prayers’ to ‘Prayers and Reflections.’

Minderhoud commented in a follow-up email to me:

I certainly think that this change will dampen the calls to abandon prayer in the legislature because it gives greater consideration to atheists, agnostics and non-praying religious communities. Aside from the BC Humanist Association’s publication and one or two media stories covering their publication, however, I hadn’t heard of substantial discussions by MLAs, by the media or by other groups about reforming or abolishing prayer in the legislature.

Although this change would probably be necessary in the future if Christians desire to preserve prayers in the legislature, I wonder if faith communities gave up too much too early. Did we simply retreat to a stronger and more defensible position or did we give up ground without much of a fight? I am not convinced either way.

The Vancouver Sun article confirms that the BCHA will not be satisfied with the legislature’s modifications:

“While an undoubtedly well-meaning amendment, we ultimately want to see prayers removed from the standing orders altogether,” said Ranil Prasad, a board member of the B.C. Humanist Association. “Government prayers are not inclusive of the overwhelming majority of British Columbians who are not religious, they violate the principle of separation of church and state and, frankly, they are a waste of both taxpayer money and time in the chamber.”

“While an undoubtedly well-meaning amendment, we ultimately want to see prayers removed from the standing orders altogether,” said Ranil Prasad, a board member of the B.C. Humanist Association. “Government prayers are not inclusive of the overwhelming majority of British Columbians who are not religious, they violate the principle of separation of church and state and, frankly, they are a waste of both taxpayer money and time in the chamber.”

The BCHA is targeting more than prayers in the Legislative Assembly. Bushfield’s December 2 newsletter makes that clear:

The fact that MLAs opted to keep the prayers in prayers and reflections shows that our politicians still feel like they can’t fully end the state endorsement of religion. We see this as well in the words of O Canada, which were recently made gender neutral but MPs were unwilling to touch the religious language in it.

More tangibly, this also shows itself in the handouts given to religious private schools and hospitals, the property tax exemptions uncritically afforded to churches, the immunity from human rights laws for religious groups and who can perform marriages.

Not only do the humanists want to challenge prayer – and more – they also rely on a false premise.

Separation of church and state

When the BCHA representative told The Vancouver Sun that “government prayers . . . violate the principle of church and state,” he misrepresented the situation, at least from the point of view of most Christians involved in such issues.

ARPA Canada makes this statement regarding ‘Separation Between the Institutions of Church and State’:

Jesus said that we are to “render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and to God the things that are God’s” (Matthew 22:21). The implication is that the church, as an institution, should not direct the affairs of the civil government and vice versa. But this does not mean that faith or religion has no role in the state. It is impossible to make public policy without a moral foundation and direction. The state should protect the place of the church in society so that the church can do its calling which includes equipping its members to honour the state and to function constructively to God’s glory within our democracy.

Bruce Clemenger

Bruce Clemenger, president of the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada, says this:

The notion of the ‘separation of church and state’ is derived from the First Amendment of the US Constitution – about non-establishment of religion and the free exercise of religion etc. Canada has no parallel constitutional provision. We do not have a state church.

In Canada, the state can and does collaborate with religious institutions – grants, CIDA funding, summer job grants, funding to religious schools etc.

Rather than an issue of ‘church and state’ and the matter of establishment or collaboration between institutions, this issue is about faith expression and state functions and not about religious institutions.

He pointed to several (very helpful) comments he has written on related issues, particularly related to whether it is permissible to allow expressions of religious belief within state institutions:

- Competing views on state neutrality

- Three understandings of faith neutrality

- Prayer at government meetings: reflections on the Saguenay case

- Will religious observance be allowed at government functions?

The last article discusses a Supreme Court of Canada case which considered whether Saguenay (Quebec) city council could properly open its sessions with prayer. Clemenger recognized that Christians themselves might have a range of opinions about prayer in government settings:

Evangelicals disagree about what city councils should do. Some prefer a prayer, some would find a moment of silence acceptable, and others don’t think any prayers should be offered.

He also said:

Perhaps the reason the Court did not take a definitive stand is that, as the Court noted, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms does not require the state to be religiously neutral: “Neither the Quebec Charter nor the Canadian Charter expressly imposes a duty of religious neutrality on the state. This duty results from an evolving interpretation of freedom of conscience and religion.”

The Court is contending that the best way to protect conscience and religion is for the state to be neutral with respect to the differing religious views and beliefs of citizens. This, they said, extends to atheists and agnostics.

Go here for the full comment.

Need to get involved

Where most Christians would agree, I imagine, is that we do not want the BC government of the day deciding upon issues of significance to religious groups based solely upon submissions from a stridently secular group such as the BC Humanist Association.

ARPA Canada is doing very good work, but they could use some support. Is there a way we could support them, or come alongside them through our denominations and/or ecumenical organizations, particularly on local issues which will affect the practice of our faith?

A December 4 Angus Reid / Cardus poll underlines some of the points made in this article. Here is the first paragraph of a Cardus release:

A December 4 Angus Reid / Cardus poll underlines some of the points made in this article. Here is the first paragraph of a Cardus release:

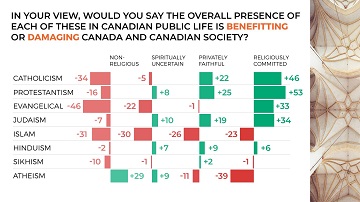

The findings of a new Angus Reid Institute (ARI) survey, produced in partnership with Cardus, are raising questions about the future of tolerance and virtue in Canada. The 2019 Public Faith Index has found that the more religious Canadians are, the more likely they are to take a positive view of faiths different from their own.

By contrast, when non-religious Canadians were asked whether various faiths were “benefitting or damaging Canada and Canadian society,” they took a dim view of every community but their own.

Go here for the full release.