Creating Conversation is a weekly editorial, curated by the Centre for Missional Leadership (CML), and gives opportunity for people to speak about issues they believe are vital for the church in Vancouver.

One of the goals of this weekly article is to spark dialogue – and action. We invite you to join the dialogue here on the Church for Vancouver website.

We also invite you to use the article as a discussion starter with your small group, church staff, friends and your neighbours. Thanks for participating in the conversation!

Back in March 2020, when COVID-19 first led the world into a pandemic shutdown, we quickly pivoted and learned how much of our work and life could be carried out from the safety of our own homes. Whole offices began to work remotely, grocery delivery became commonplace and universities began offering all their classes online.

The church was also thrown into a season of adaptation where we collectively went to great lengths to include as many people as possible in our shared life. Congregations which had never considered online services were streaming on Sunday morning, teenagers where helping seniors set up tablets and sermon manuscripts were being snail-mailed to those who did not have internet access. It was a Covid grace that we learned so much, so quickly, about inclusion.

Now I find myself reflecting on this rapid period of inclusion. There are lots of reasons why people are excluded, such as age, race, sexuality, gender . . . and yes, I know that the word inclusion can be a bit of a trigger.

People with disabilities

While I don’t want to downplay those topics, I do want to focus on one specific inclusion which has been highlighted by our pandemic experience – the inclusion, or perhaps better said, the exclusion of people with disabilities.

It is necessary to say a word about terminology. There is no one universally accepted term to use, as individuals with different abilities have different preferences. As most disability advocates strive to use the language that individuals use to describe themselves, and as it is currently most common for individuals to use the word disability, I will honour that and use the word disability.

I also approach this subject humbly, knowing that the lens I see the world through is one of an able-bodied experience.

Disabilities are common, perhaps more common than we think. They can be permanent or temporary, be present from birth or develop at any point of life. Disabilities are not only physical, but cognitive, intellectual or developmental. They can be visible or hidden.

While disabilities are common, unfortunately discrimination towards disabled people is also very common. There are many types of isms, such as racism, ageism, sexism. Discrimination or prejudice towards people with disabilities is called ableism.

Ableism

Ableism can be blatant and aggressive, such as refusing to make physical accommodations for someone with a disability to access services. However, some prejudice is subtle and happens without us even really being aware, such as when we use the language “that’s lame” or “she’s crazy.” When our buildings, our communities and our society are built around the able-body experience, the discrimination is systemic.

Churches and the people who attend churches are not immune to ableism. Christianity has a complicated relationship with people with disabilities. With such a heavy focus on Jesus healing people, at best our churches have ignored the call to be inclusive of people with diverse abilities, and at worst they have questioned people’s faith when individuals have not been healed.

Here are a few examples of ableism people have shared with me:

- One person being told that if they had enough faith they wouldn’t need their wheelchair.

- A person with ADHD being reprimanded by leaders when they needed to get up and move during the service.

- An autistic child being refused communion because they might not fully understand the sacrament.

Perhaps you have heard of more or have, unfortunately, been on the receiving end of ableism from the church.

In our ableist actions, we as the church have said that people with disabilities are a second class of Christians – as if they aren’t worthy of being part of the family of God, being part of the body of Christ or that they are not made in the image of God.

Not a prayer request

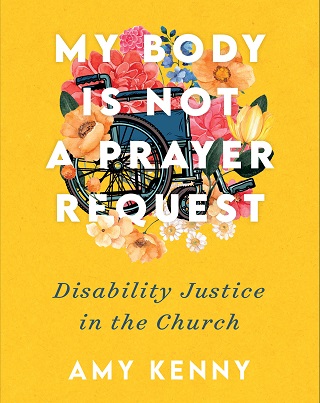

Amy Kenny is a Shakespeare scholar and disabled; she uses a wheelchair for mobility. She shares this reflection in My Body is Not a Prayer Request (Brazos Press, 2022):

Amy Kenny is a Shakespeare scholar and disabled; she uses a wheelchair for mobility. She shares this reflection in My Body is Not a Prayer Request (Brazos Press, 2022):

I bear the image of the Alpha and the Omega. My disabled body is a temple for the Holy Spirit. I have the mind of Christ. There is no caveat to those promises. I don’t have a junior holy spirit because I am disabled.

To suggest that I am anything less than sanctified and redeemed is to suppress the image of God in my disabled body and to limit how God is already at work through my life.

It is not an us and them, disabled and not disabled. It is about doing and being in ministry together, with one another. This formation presents a different view of the body of Christ, one that is perhaps closer to Paul’s original description, where the weaker and vulnerable members of the body are clothed with honour and greater respect:

The eye cannot say to the hand, “I have no need of you,” nor again the head to the feet, “I have no need of you.” On the contrary, the members of the body that seem to be weaker are indispensable, and those members of the body that we think less honourable we clothe with greater honour, and our less respectable members are treated with greater respect.” 1 Corinthians 12:21-23

Reflecting on this passage in his book The Bible, Disability and the Church (Eerdmans, 2011) Amos Yong makes the point that the limbs are the parts of the body that get all the glory. They are the ones on the outside, able and obvious to the world, but they are also disposable. One can live without their fingers, or even without a leg, but we go to great lengths to care for our delicate and unseen organs. These precious organs, like our kidneys or liver, are kept in the centre, protected and preserved.

Positions of honour

When I think back through our scriptures, this is actually a more accurate description for how disabled people have been part of the kingdom of God. Not only have they been kept safe and protected, but put in positions of honour.

In fact, disabled people have been integral to our story as the chosen people of God.

- Isaac went blind.

- Jacob limped after wrestling with God.

- Leah had weak eyes.

- Moses had a speech impediment.

- Elijah was depressed and had suicidal thoughts.

- Timothy had some IBS or delicate bowels.

- Paul had some sort of chronic pain, a thorn in his flesh.

And the list goes on. When we look closely at scripture, the story of God’s people is full of disabled people. People who despite, or perhaps because of, their disability were called to join in with God’s work. Including people with disabilities is part of our history.

There isn’t space here to go into the details of disability theology, or to exegete biblical texts (I’ll leave that for the bibliography below). What if we lived into this image with the body of Christ, creating a formation where we keep our more delicate and vulnerable, but special and precious members, safe and at the centre.

We as leaders (formal and informal, clergy and lay) have such great influence on who is included in our communities and who is excluded. There are already so many societal forces that push the normate view, saying that able-bodied is what we should all strive for, and that anything less . . . is, well, less.

We are called to invite people to another way where we confidentially share a gospel that says each of us is worthy and a beloved child of God.

What should change?

So what changes can congregations make to better include people with disabilities? The physical and built world are important, and with an ageing population many of our buildings have been adapted and renovated to help include people with physical disabilities.

Yet, there is so much more that can be done. A few small changes that can go a long way include: closed captioning with our streamed services, using more visual aids during sermons, leaving more silence for people to reflect and providing opportunities for movement during services. We should ask disabled people what they need to be included.

One thing that we learned through the pandemic was that we can quickly adapt how we do things. We moved worship services online in a matter of days and found ways for each person to be included in community.

Yet, there is a slightly sour note to this statement, because now that most of us have been able to return to in person worship, has the online version been left behind? With the priority being put on in person worship, have we forgotten, or excluded those who cannot return to in person worship?

The barriers for disabled people to be included in worship can be high, but when their inclusion is a priority and they are placed at the centre of our gatherings, it actually helps to include even more people.

For example, meaningful inclusion of people through online worship means that parents with young children, those who are immune-compromised or work/live with those who are immune-compromised, individuals with social anxiety or people with transportation barriers can also gather, meaningfully and easily.

When we clothe our precious members of our community with honour, value them and elevate them at the centre of our gatherings, inclusion can take new forms. How we gather together can be done in ways that remind each one of us that we are loved by God, that we are a gift to each other and that we are being transformed by God.

Resources

Andrea Perrett

This brief dip into disabilities and theology could only skim the surface. Here are some suggestions for further reading:

- Amy Kenny: My Body is Not a Prayer Request

- Amos Yong: The Bible, Disability, and the Church

- Bethany McKinney Fox: Disability and the Way of Jesus

- Brian Brock: Disability

- Nancy Eisland: Disabled God

- Candida Moss: Divine Bodies

- John Swinton: Becoming Friends with Time

Andrea Perrett is an Associate in New Witnessing Communities with the Centre for Missional Leadership at St. Andrew’s Hall. She is the Director of Cyclical Vancouver, a local church planting network.