This article is part of a series called ‘Christianity: a missionary religion.’

This article is part of a series called ‘Christianity: a missionary religion.’

As I said in the introduction to the series, mostly, I’ll look at recently published books. It is encouraging to see that, while most churches and Christian bookstores have largely forgotten missionaries, a few publishers continue to produce some fascinating books.

Some are devotional; some are aimed at the Christian public. But many have an academic focus, both from within the Christian community and from secular publishers.

No longer do we see much in the way of hagiography (probably a sign of maturity) and many are critical of the missionary movement. But they do take it seriously.

It probably goes without saying that I will just scratch the surface of each topic (at times simply quoting from the publishers) – but I do hope people will go on to read some of the books, which are of high quality.

Were missionaries an intrinsic part of the British and American imperial / colonial projects? Some vehemently say yes, others offer many caveats and contradictions – but there is no doubt that there has been a considerable overlap over the past couple of centuries.

Fortunately, many new books are allowing us to get a better handle on our missionary history.

- Emily Conroy-Krutz: Christian Imperialism: Converting the World in the Early American Republic (Cornell University Press, 2018)

- Emily Conroy-Krutz: Missionary Diplomacy: Religion and Nineteenth Century American Foreign Relations (Cornell University Press, 2024)

Emily Conroy-Krutz was quite clear on the point in Christian Imperialism (Cornell University Press, 2018).

Emily Conroy-Krutz was quite clear on the point in Christian Imperialism (Cornell University Press, 2018).

“In 1812, eight American missionaries, under the direction of the recently formed American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, sailed from the United States to South Asia.

“The plans that motivated their voyage were no less grand than taking part in the Protestant conversion of the entire world. Over the next several decades, these men and women were joined by hundreds more American missionaries at stations all over the globe.

“Emily Conroy-Krutz shows the surprising extent of the early missionary impulse and demonstrates that American evangelical Protestants of the early 19th century were motivated by Christian imperialism – an understanding of international relations that asserted the duty of supposedly Christian nations, such as the United States and Britain, to use their colonial and commercial power to spread Christianity.”

Her new book, Missionary Diplomacy, delves more deeply into the situation, highlighting the many ways in which missionaries influenced American foreign policy.

“Missionary Diplomacy illuminates the crucial place of religion in 19th century American diplomacy. From the 1810s through the 1920s, Protestant missionaries positioned themselves as key experts in the development of American relations in Asia, Africa, the Pacific and the Middle East.

“Missionaries served as consuls, translators and occasional trouble-makers who forced the State Department to take actions it otherwise would have avoided. Yet as decades passed, more Americans began to question the propriety of missionaries’ power. Were missionaries serving the interests of American diplomacy? Or were they creating unnecessary problems?

“As Emily Conroy-Krutz demonstrates, they were doing both. Across the century, missionaries forced the government to articulate new conceptions of the rights of US citizens abroad and of the role of the US as an engine of humanitarianism and religious freedom.

“By the time the US entered the first world war, missionary diplomacy had for nearly a century created the conditions for some Americans to embrace a vision of their country as an internationally engaged world power. Missionary Diplomacy exposes the longstanding influence of evangelical missions on the shape of American foreign relations.”

During a YouTube video on her book last summer, she gave some examples of issues that arose around the world:

Part two of the book really gets us into kind of the meat of this story and what I call ‘missionary troubles.’ These chapters hop around the globe, focusing on a few key themes, including citizenship, the consular service, violence against missionaries and missionary troublemaking – which is some of the language that we see the State Department using over the course of the century . . .

What rights citizens have abroad is not always clear, nor is it always clear who gets to claim those rights of citizenship. And so missionaries, as they’re going out into the world in this period, really expecting to spend their entire lives outside of the United States once they leave, coming back for a kind of furlough trips and things like that. . . .

They insist that still they are US citizens who deserve the protection of the state to go about what they call their legitimate business. And that includes building schools, hospitals, selling books and, of course, itinerating and proselytizing. And they have to make this claim over and over again, precisely because their ability to do it is challenged in different times and places.

A review of the Missionary Diplomacy in The Christian Century makes a couple of key points, pointing both to overweening cultural confidence and to actual achievements:

The name of this magazine denotes its founders’ enthusiasm at the dawn of the 20th century for the Protestant missionary enterprise, which, the theory went, would soon convert whole sections of the world’s peoples to Christianity, ushering in not only a distinctive but a self-evidently superior historical era. This overly optimistic view became subject to self-examination in the Century beginning in the 1920s and then with greater force in the 1930s. . . .

Drawing on a wealth of sources – diplomatic correspondence, records of such organizations as the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions and of individual missionaries, and contemporary Christian and secular periodicals – Conroy-Krutz demonstrates that one cannot understand the growth of US diplomacy beyond Europe and Latin America without reference to the missionary enterprise.

A good book to read in conjunction with Missionary Diplomacy would be David Hollinger’s Protestants Abroad: How Missionaries Tried to Change the World but Changed America, which I wrote about here.

- Philip Dow: Accidental Diplomats: American Missionaries and the Cold War in Africa (William Carey Publishing, 2024)

In the 20th century, a hidden chapter of the Cold War unfolded in Africa, shaped by American evangelical missionaries.

In the 20th century, a hidden chapter of the Cold War unfolded in Africa, shaped by American evangelical missionaries.

“Accidental Diplomats uncovers this lesser-known story, revealing how these missionaries’ quest to spread the gospel intersected with global geopolitics. Their spiritual mission had an unforeseen impact on the socio-political dynamics of the era.

“This book offers a deep dive into the complex interplay of evangelical missions, African politics and Cold War strategies. It explores the significant yet subtle role of faith in shaping international relations and cultural transformations in Congo, Ethiopia and Kenya. The narrative brings to light key events and influential figures, unraveling the intricate web of religion and global power politics.”

Melani McAlister, a renowned historian and author of several books – including The Kingdom of God Has No Borders: A Global History of American Evangelicals (Oxford University Press, 2018), which I included in Part VI of this series.– wrote the Foreword to Accidental Diplomats.

She said:

For me, what makes this a particularly important book is the fact that Dow brings together the advantages of an insider’s perspective – he engages deeply with the issues of conversion, community norms and morality that were important to the missionaries – with the rigor and critique of a first-class scholar.

He shows how missionaries in all three countries, but especially Congo, were often deeply compromised by racism and even segregationist ideologies. Most crucially, however, Dow argues that it was the relatively democratic and open structure of evangelical churches that provided spaces and practices for thinking about democracy and power in nations that were learning how to govern themselves.

He recounts in detail ways in which American missionaries could be culturally arrogant and presumptuous, even greedy, across all three countries. But he also shows how other missionaries lived simply among local people, sharing in their way of life, loving and becoming loved in return. . . .

This is, in the end, a book about the often-inadvertent work that American missionaries did for the US state during the Cold War. But it is also about the relationships within the mission community and their converts, how trust or the lack of it, racism, or its refusal, could and did create a network of believers, African and American, who struggled with what they owed their church, their states and each other.

- Philip Jenkins: Kingdoms of This World: How Empires Have Made and Remade Empires (Baylor University Press, 2024)

Commenting on Kingdoms of This World, Brian Stanley, Professor Emeritus of World Christianity, University of Edinburgh, stated:

Commenting on Kingdoms of This World, Brian Stanley, Professor Emeritus of World Christianity, University of Edinburgh, stated:

Empires have been the default setting of political organization throughout the ages. As such, their history is interwoven with the formation and expansion of the world’s great religions in intricate and ambiguous patterns.

Philip Jenkins’ book, founded on an extraordinary range of reading, uncovers those patterns with rare insight and comprehensiveness. This work demands the attention of scholars of both religion and imperialism, and of all those who wish to understand the religious and ideological contours of the modern world.

Jenkins put missionary history into context:

“Throughout history, the world’s great religions have been profoundly shaped by their encounters with successive empires. Secular empires have provided the means by which religions achieve their global scale, and any worthwhile historical account of those religions must reckon with that imperial dimension.

“In some cases, empires have favoured and supported particular faiths, while in other instances they have suppressed traditions they feared or distrusted. . . .

“Kingdoms of This World is the first full-length study of the imperial contexts of the world’s religions. Philip Jenkins offers extensive coverage of Christianity, Buddhism, Islam, Judaism, Sikhism and other faiths, and ranges widely in tracing the imperial histories of many different parts of the world.”

Jenkins writes:

Christian missions advanced the interests of those emerging empires and indeed justified their existence. Commonly, the linkage worked in the interests of both sides: the cross followed the flag, and the flag followed the cross.

Yet the imperial context was by no means simple. If missions and missionaries were indeed the vanguard of worldly empires, this would compromise the spiritual content of the message they were preaching. It posed the danger that external societies would dismiss missions solely as pawns or tools of hostile empires and would strike back at them accordingly.

Jenkins has contributed much to our understanding of world Christianity, with books such as The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity, The Lost History of Christianity: The Thousand-Year Golden Age of the Church in the Middle East, Africa and Asia – and How it Died and Climate, Catastrophe and Faith: How Changes in Climate Drive Religious Upheaval.

- Nigel Biggar: Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning (William Collins, 2023)

Earlier in this series I looked at some really obvious overlaps of imperialism and missionary activity, along with examples of missionaries opposing at least the excesses of colonial power.

Still, even with positive examples of missionary activity, there remain legitimate critiques, mainly related to a kind of cultural imperialism – an assumption that they were part of a ‘civilizing’ influence.

For example, Oxford professor Nigel Biggar, in Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning (William Collins, 2023) – widely criticized, and applauded, for its measured appreciation of the British Empire – writes:

Inspired by a Christian ideal of basic human equality, a popular national movement arose in late 18th century Britain to bring about the abolition, first, of the trade in slaves from Africa across the Atlantic to the Caribbean and the American colonies, and subsequently of the institution of slavery itself throughout the empire.

Thereafter, Christians and other humanitarians called for the British government to intervene in faraway parts of the world – especially West, South and East Africa – to suppress slavery.

For example, in the early 1860s, the famous Christian missionary, physician and explorer David Livingstone lobbied for the establishment of British imperial administration in the Shire Highlands of what is now Malawi, in order to provide a stable political environment for the development of cash crops and commerce as a necessary alternative to the trade in slaves.

- Ulinka Rublack, editor: Protestant Empires: Globalizing the Reformations (Cambridge University Press, 2024)

“Protestantism during the early modern period is still predominantly presented as a European story.

“Protestantism during the early modern period is still predominantly presented as a European story.

“Advancing a novel framework to understand the nature and impact of the Protestant Reformations, this volume brings together leading scholars to substantially integrate global Protestant experiences into accounts of the early modern world created by the Reformations, to compare Protestant ideas and practices with other world religions, to chart colonial politics and experiences and to ask how resulting ideas and identities were negotiated by Europeans at the time.

“Through its wide geographical and chronological scope, Protestant Empires advances a new approach to understanding the Protestant Reformations. . . . this volume demonstrates how global interactions and their effect on Europe have played a crucial role in the history of the ‘long Reformation’ in the 17th and 18th centuries.”

Harvard professor David Armitage wrote of Protestant Empires:

Protestant Empires cross-fertilizes two of the most productive trends in early modern historiography: the globalization of history and the pluralization of the Reformation. In its richly researched chapters, an all-star cast of scholars kaleidoscopically portrays how Protestantism spread ‘to the ends of the earth’ with transformative effects from the Americas to Asia.

- Gareth Atkins: Converting Britannia: Evangelicals and British Public Life, 1770 – 1840 (Boydell Press, 2024)

Another book not directly focused on missions, but which provides solid insights into the ground from which the movement flourished in the 19th century, is Converting Britannia.

Another book not directly focused on missions, but which provides solid insights into the ground from which the movement flourished in the 19th century, is Converting Britannia.

“:The moralism that characterized the decades either side of 1800 – the so-called ‘Age of William Wilberforce’ – has long been regarded as having a massive impact on British culture.

“Yet the reasons why Wilberforce and his Evangelical contemporaries were so influential politically and in the wider public sphere have never been properly understood. Converting Britannia shows for the first time how and why religious reformism carried such weight.

“Evangelicalism, it argues, was not just an innovative social phenomenon, but also a political machine that exploited establishment strengths to replicate itself at home and internationally.

“The book maps networks that spanned the churches, universities, business, armed forces and officialdom, connecting London and the regions with Europe and the world, from business milieux in the City of London and elsewhere through the Royal Navy, the Colonial Office and East India and Sierra Leone companies.

“Revealing how religion drove debates about British history and identity in the first half of the 19th century, it throws new light not just on the networks themselves, but on cheap print, mass-production and the public sphere: the interconnecting technologies that sustained religion in a rapidly modernizing age and projected it into new contexts abroad.”

Writing for Church Times, William Jacob noted that the British and Foreign Bible Society and the Church Missionary Society were major recipients of “large increases of philanthropic giving.”

- Felicity Jensz: Missionaries and Modernity: Education in the British Empire, 1830 – 1910 (Manchester University Press, 2022)

“The 19th century saw dramatic change in the self-assumed role of evangelical Protestant mission schools as one of the primary institutions of moral reform in the 19th century British colonial world.

“Drawing on key moments in the development of missionary education from the 1830s to the beginning of the 20th century, this study examines the changing ideologies behind establishing mission schools and the provision of ‘liberal and comprehensive’ education in shaping non-Europeans into ‘useful’ and ‘modern’ members of empire.

“It examines the Negro Education Grant in the West Indies, the Aborigines Select Committee (British settlements) and missionary conferences as well as drawing on local voices and contexts from Southern Africa, British India and Sri Lanka to demonstrate the changing expectations for, engagement with, and ideologies circulating around mission schools resulting from government policies and local responses.

“By the turn of the 20th century, many colonial governments had encroached upon missionary schooling to such an extent that the symbiosis that had allowed missionary groups autonomy at the beginning of the century had morphed into an entanglement that secularized mission schools.

“The spread of ‘Western modernity’ through mission schools in British colonies impacted local cultures and societies. It also threatened Christian religious moral authority, leading missionary societies by the World Missionary Conference in Edinburgh in 1910 to question the ambivalent legacy of missionary schooling and to fear for the morality and religious sensibilities of their pupils and indeed for morality within Britain and the Empire.”

In “positioning” Missionaries and Modernity, Felicity Jensz writes:

The role of missionaries in Indigenous education was and is ambiguous and often contradictory, with contemporaneous observers as well as recent scholars often divided over how to evaluate the results of missionary education.

Some scholars view missionary education as a humanitarian rather than imperialist act, while others focus upon the detrimental nature of missionary education in terms of cultural destruction and cultural hegemony.

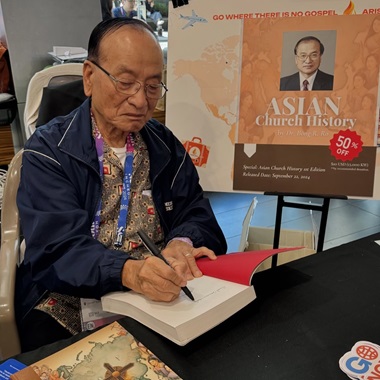

Bong Rin Ro writes positively about missionary education.

While attending the Lausanne 4 Congress in Korea last fall, I heard several Christians from around the world support the humanitarian view. I met veteran Korean author and teacher Bong Rin Ro, and bought his book, Asian Church History – which I wrote about in Part IX of this series:

Though he is particularly enthusiastic about the dynamic Asian church and mission movement, he does acknowledge and give credit throughout the book to Western missionaries and their influence.

For example, regarding education: “The traditional educational system in Asia was basically for the children of the elite aristocratic class . . . Missionaries brought modern education to Asia and revolutionized the educational system of most Asian nations.”

While drawing on and agreeing with earlier studies of missionary education, Jensz says she “takes a slightly different approach by placing the dynamic ideologies of missionary education in the foreground.”

- Sathnam Sanghera: Empireland: How Imperialism Has Shaped Modern Britain (Viking / Penguin, 2021)

It is interesting to note that a book which “shows how the pernicious legacy of Western imperialism undergirds our everyday lives, yet remains shockingly obscured from view” does not engage much with Britain’s missionary legacy.

It is interesting to note that a book which “shows how the pernicious legacy of Western imperialism undergirds our everyday lives, yet remains shockingly obscured from view” does not engage much with Britain’s missionary legacy.

He does write in Empireland:

There was an extended period between 1660 and 1807 when Britain profiteered from the evils of the Atlantic slave trade . . . but then, after Parliament had outlawed slavery, it took a leading role in abolishing it.

There was a long period when missionaries were discouraged, for fear that they might disrupt the imperialists’ work, but then missionaries were encouraged, with empire beginning to see itself as a civilizing mission.

Later he adds an important note about an ironic, or at least unexpected turn in the missionary movement:

. . . British missionaries once headed out in droves to spread Christianity across the empire, but nowadays the average unbelieving Briton is more likely to be on the receiving end of such zeal, The Times reporting in 2016 that “Christians from converted countries are now engaging in ‘reverse mission’ to reintroduce God to an increasingly secular Britain.

The ‘Christianity: a missionary religion’ series:

• Introduction

1. History of Missions

2. State of World Christianity

3. Specific Areas: Africa

4. Specific Areas: Asia

5. Specific Areas: Latin America

6. Not So Good News

7. New Approaches to Missions

8. Women

9. Specific Areas: Asia

10. Imperialism / Colonialism