With Mission Fest upon us (February 15 – 17 at Westside Church) I have been posting a series on Christianity as a missionary religion:

With Mission Fest upon us (February 15 – 17 at Westside Church) I have been posting a series on Christianity as a missionary religion:

1. History of Missions

2. State of World Christianity

3. Specific Areas: Africa

4. Specific Areas: Asia

5. Specific Areas: Latin America

6. Not So Good News

7. New Approaches to Missions

I will look mainly at some of the new books covering these various areas, but will also try to cover a few key themes along the way. It probably goes without saying that I will just scratch the surface of each topic – but I do hope that people will go on to read some of the books, which are of high quality.

IV. Specific Areas: Asia

Being located on the Pacific Rim and having a large Asian population, we in Vancouver have had more exposure to the missionary enterprise in Asia than to other parts of the world, .

A couple of Catholic missionaries – Francis Xavier and Matteo Ricci will be widely recognized, and Hudson Taylor and William Carey are still remembered today. Others such as James Legge, Jonathan Goforth, Pearl Buck (daughter of missionary parents), Gladys Aylward and Lottie Moon are well known in various Christian circles.

At least one of China Inland Mission’s prolific authors came from here. Isobel Kuhn and her husband John spent a quarter of a century with the Lisu people in southwestern China. I wrote about how their work is still remembered there.

Here are some recent books which offer glimpses into Asian missions. Some of the write-ups will reflect my thoughts; others (in quotes) will simply be descriptions from the publisher. Most of the books relate to China, but I will start with one about Southeast Asia.

- Kiem-Kiok Kwa & Samuel Ka-Chieng Law, editors: Missions in Southeast Asia: Diversity and Unity in God’s Design (Langham Global Library, 2022)

Christian History magazine featured Adoniram and Ann Judson, describing them as “pioneers of the American missionary movement.” They worked in Burma (Myanmar), where she died at 37; he remained there for almost 40 years.

Southeast Asia is a key region in the 21st century, a strategic link between the Middle East and the Pacific, and with a population almost as large as Europe. But it is still overlooked, not least by those assessing the state of World Christianity. Missions in Southeast Asia seeks to remedy that problem.

The first half of the book is devoted to histories of Christianity in eight nations, individually. While there is some common ground, each story is unique. The second half “deals with broad issues which affect all the Southeast Asian countries, reinforcing the commonalities that arise from geographical proximity.”

Most of the nations have had some Christian contact for many hundreds of years, but colonial and missionary influences have been more significant in the past couple of centuries.

Each chapter describes the missionary history of the nation being covered. Christianity is very much a minority faith in most of the nations – in some cases a very small minority (in Cambodia and Thailand just a couple of percent).

Myanmar’s Christian population is about 7 percent, with Malaysia, Indonesia and Vietnam approaching 10 percent. Singapore has maybe 20 percent, and the Philippines is majority Christian, mainly Catholic.

(Going by figures in the book, but also in Global Christianity.)

There is good news, but the authors don’t shy away from critique either.

- Cambodia

Kevin Knight (from Vancouver) and his wife Leakhena Phan live and work in Tang Khiev, Cambodia.

For example, Samuel Law, one of the editors, reports the amazing growth of the church in Cambodia since the Khmer Rouge decimated it in the 1970s:

Today, however, the church in Cambodia is a testament to God’s faithfulness as it emerges from one of the darkest moments of human history.

Not only do the numbers of Christians and churches exceed pre-1975 numbers, the Christian witness of redemption has been woven into the rebuilding of the nation through the transformative testimonies of thousands of Khmer Rouge members who have converted to Christianity.

But he warns that the depth of faith is often questionable. Regarding for Khmer Rouge believers, for example, he quotes one church leader: “People receive baptism until the fishes recognize their faces” – possibly reflecting a Buddhist karmic worldview.

He also points out that the Cambodian church “is a reflection of ‘glocalization,’ in which the forces of globalization are contextualized through the lens of the local narrative.” He is concerned about global influences:

Four challenges are highlighted: (1) the need to develop a local Christian identity; (2) self-sufficiency; (3) the critical need for contextual theology and the lack of theological education for both clergy and laity; and (4) an appropriate missional model for the future Cambodia.

Several individuals and groups with local connections – Brian McConaghy (Ratanak International); Kevin Knight (Manna 4 Life); Craig Greenfield (Alongsiders International); Patrick Elaschuk and others (Tenth Church), for example – have been heavily involved with Cambodia (and are committed to a strong indigenous Cambodian church).

- Singapore

Singapore has a much stronger Christian presence than Cambodia. Writer Andrew Peh says the percentage of the population identifying itself as Christian grew from about 10 in 1980 to almost 19 percent in 2015. He quotes Robbie Goh as commenting that Christianity “is the religion with the strongest representation among the well-educated” and “has a strong association with middle-class status.”

Women’s Bible study scene from ‘Crazy Rich Asians.’

A mixed blessing. Peh adds:

In telling the story of Christianity in Singapore, Brett McCracken aptly alludes to the movie Crazy Rich Asians (2018), which has for its opening scene a group of wealthy Singaporean tai tais (rich housewives) having a Bible study in a palatial home.

He notes, “The dichotomous scene plays for laughs, but it captures one of the unique contours of Christianity in Singapore – a nation whose affluence and piety often coexist, for good and ill. . . .

The churches in Singapore must take heed, for history will show if the substance of our richness is ultimately defined by the kingdoms of this world or the kingdom of God.

During a brief visit to Singapore a few years ago, I sat in on a Full Gospel Business luncheon which featured a rags to riches testimony from a wealthy businessman who grew up with many siblings sleeping side by side on the floor. His story was inspiring, and clearly Christian – but the potential temptations were evident.

Peh notes that Singapore is sometimes referred to as ‘the Antioch of the East’ because it is one of the highest per capita missionary-sending nations. He has reservations about the appellation, but it is certainly true that Singapore is a key base for the Asia Pacific region and beyond. Many well known mission organizations, including OMF, OM, SIM International and Wycliffe, have bases there.

I posted ‘Lessons from Singapore: the long path to discipling the nations’ in 2019.

- Indonesia

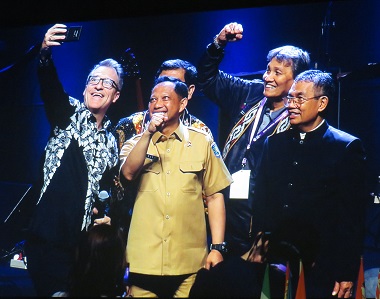

Several WEA leaders on stage with Indonesian Minister of Home Affairs Tito Karnavian at the General Assembly.

Benyamin Intan writes that “It has not been easy for Protestant Christians to exist and bear witness in Indonesia due to Dutch colonialism,” with which the majority-Muslim population linked them.

However, he adds, “Protestant Christians played a pivotal role in the nationalist movement.” They also contributed to religious freedom:

The pinnacle of Protestant Christians’ contribution to national unity was seen in the strategic role they played in the formation of Pancasila, Indonesia’s national ideology, whereby a united Indonesia could be secured

Pancasila is the Indonesian state philosophy, which rests on Five Principles: the belief in one God, just and civilized humanity, Indonesian unity, democracy under the wise guidance of representative consultations and social justice for all the peoples of Indonesia.

Christians managed to resist the insertion of words which would have treated Islam as the ideological basis of the state in the Preamble and body of the Constitution.

Theory and practice do not entirely match up however:

[T]he struggle of Christians for Indonesia to extend equal treatment of its citizens still had a long way to go. . . . The state’s concession to Islam as a majority religion whose adherents demand privileges has naturally caused discrimination against non-Muslim minorities, especially Christians. . . .

If the Christian witness in the life of the nation and the state is to persist in the future, there must no longer be a gap between the aspirations of Indonesia’s founding fathers as expressed in the Constitution and the reality of Indonesian politics.

Fortunately, there are moves within Indonesia and abroad to strengthen the Pancasila model.

When the World Evangelical Alliance held its General Assembly in Jakarta in November 2019, they welcomed a key Muslim leader. I wrote at the time:

When the World Evangelical Alliance held its General Assembly in Jakarta in November 2019, they welcomed a key Muslim leader. I wrote at the time:

A rather dramatic presentation on the final evening of the gathering confirmed the fact that Indonesian churches have been developing good relationships with leaders. The Indonesian Minister of Home Affairs (and former National Police Chief), Tito Karnavian, delivered an address which had not been scheduled.

He said he was “honoured and really proud” to host the WEA, adding that Christianity could be a positive influence over radicalized Muslims. He added, “I like peace because I’m the former Chief of Police. . . . I am a Muslim, but I’m a moderate Muslim . . . we strongly believe that Islam is a religion of peace.”

The WEA has cultivated relationships developed in Indonesia. In 2021 Paul Marshall wrote ‘The world’s largest Muslim organization just honored evangelicals’ for Religion Unplugged, noting that leaders of Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), the world’s largest Muslim organization, honoured the newly installed head of the World Evangelical Alliance.at the International Religious Freedom Summit held in Washington, D.C. July 13 – 16:

This meeting’s origins stem from a NU/WEA meeting in November 2019, in Jakarta, Indonesia, which led in April 2020 to the two groups forming a joint working group to counter two threats to religious freedom and to society more broadly: religious extremism and secular extremism.

The two groups stress that they are not seeking to meld their theologies: they remain fervently Christian and fervently Muslim, but they want to work together, and to respect and love one another.

Christianity Today posted ‘Parsing Pancasila: How Indonesia’s Muslims and Christians Seek Unity’ late last year, interviewing three moderate Muslims and three Christians.

- Sonya Grypma: Nursing Shifts in Sichuan: Canadian Missions and Wartime China, 1937-51 (UBC Press, 2021)

Nursing Shifts in Sichuan takes on a distant time and place, but the author and publisher are local.

Nursing Shifts in Sichuan takes on a distant time and place, but the author and publisher are local.

Sonya Grypma was Vice Provost of Graduate Studies at Trinity Western University when she wrote the book. She is now an Adjunct Professor at the University of British Columbia, where UBC Press is based. She is also Past President of the Canadian Association for Schools of Nursing.

“Nursing Shifts in Sichuan illuminates modern nursing as one of the most consequential additions to early 20th century health care in China. In 1943, members of the elite Peking Union Medical College (PUMC) were forced to evacuate to the ‘backwater’ province of Sichuan, landing at the West China Union University campus in Chengdu.

“As part of an extraordinary mass migration of students and professors to Free China during the Japanese occupation, the refugee PUMC was hosted by the Canadian West China Mission for the next three years.

“Nursing Shifts in Sichuan traces the tumultuous final days of 20th century relations between China and the West. The PUMC had been so successful in its attempts to develop a Chinese nursing elite that alumnae held most of the key nursing positions in the country.

“While under evacuation, PUMC transformed nursing at the Canadian mission, initiating the second university program in China. Both programs were closed by the new Communist government in 1951; degree programs lay dormant for the next 35 years.”

The book is also full of personal stories. One local woman was Margaret Gay, who took nurses’ training at Vancouver General Hospital in 1926. Grypma points out that our hospitals were basically segregated, and “schools of nursing effectively barred women of Asian, Indigenous and African descent.” Thus:

For Canadian missionary nurses working in China, then, the idea of working with persons from other races and ethnicities, though an obvious part of their vocation, was not something they had much experience in as students in Canada.

When they arrived in China, new nurses would meet ‘mishkid’ nurses (born in China of missionary parents) who were already bilingual and bicultural. There were also some Asian nurses.

One, Agnes Chan, was the first Chinese-born nurse to graduate from a Canadian school of nursing. Born to a poor family in China in the late 1880s, she was sold to two different families in China, then to a woman in Victoria, BC. She ran away to the Women’s Rescue Home for Chinese Girls (run by the Methodist Church) before applying to, and being rejected by, several nursing schools. Eventually she was accepted by Women’s College Hospital in Toronto and in time returned to China to work in a large Methodist mission hospital.

Margaret Gay was “seconded from the Canadian North China Mission after the mission hospitals in Japanese-occupied. Henan [where she had worked for 10 years] were forced to close in 1939.”

Women’s Missionary Society secretary Adelaide Harrison wrote from Sichuan to a missionary in early 1941:

Misses Preston and Gay are finding conditions in our hospitals vastly different from [Henan] where they had ample supplies of all kinds to work with . . . Also, we do not have modern conveniences like running water and central heating, as you have, and yet in spite of all these drawbacks they are doing a fine piece of work, and I don’t know how our medical work would get along without them.

Wartime conditions proved too much for some nurses, including Gay, who returned to Canada in 1941. On her four month journey to the west from Tianjin, where she had been working with refugees, to Chongqing in the west, she had endured air raids, having to lie in a muddy gully, guarded by soldiers with bayonets; finding that bombs had destroyed her neighbourhood; passing dead bodies; and more.

West China Hospital (WCH), Sichuan University is now China’s largest comprehensive medical university. I wrote about it in ‘China’s top coronavirus-fighting hospitals have missionary roots.’ The ‘History’ page of WCH reads, “The precursors of the WCH, Cunren and Renji Hospitals were set up in 1892 by the joint efforts of Christian missions from the United States, Great Britain and Canada.”

Grypma writes that the nature of missionary nursing in China changed over the years, though “fearsome conditions had always been part of missions in China”:

This first generation of Canadian missionaries (1890s – 1920s) . . . was admired in Canada and could count on appreciative audiences back home to relay their triumphant tales. . . . In contrast, the second generation of Canadian missionaries (1930s – 1940s) belonged to an era when Canadian and American Christians were rethinking the value and purpose of missionary work, reframing Christian faith as a call to social reform rather than personal conversion.

We are still very much in that frame of mind, at least in the Western world. Time to recapture some of that early evangelistic spirit (without losing the social concern).

- Jifeng Liu: Negotiating the Christian Past in China: Memory and Missions in Contemporary Xiamen (The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2022)

Xiamen is on the coast of China, north of Hong Kong, and west of the northern part of Taiwan.

Xiamen is on the coast of China, north of Hong Kong, and west of the northern part of Taiwan.

“This volume elucidates the ways in which Christianity has become an integral part of Xiamen, a Chinese city profoundly influenced by Western missionaries.

“Drawing on extensive interviews, locally produced histories and observations of historical celebrations, Jifeng Liu [Associate Professor of Southeast Asian Studies at Xiamen University] provides an intimate portrait of the people who navigate ideological issues to reconstruct a Christian past, reproduce religious histories and redefine local power structures in the shadow of the state.

“Liu makes a compelling argument that a Christian past is being constructed that combines official frameworks, unofficial practices and nostalgia into social memory, a realm of dynamic negotiation that is neither dominated by the authoritarian state nor characterized by popular resistance. In this way, Negotiating the Christian Past in China illustrates the complexities of memory and missions in shaping the city’s cultural landscape, church-state dynamics and global aspirations.”

Liu is not a Christian. I found the way he dealt with that while writing the book interesting, especially as he said people frequently tried to convert him:

Rather than identify myself as a ‘cultural Christian,’ a term popular in Chinese society to refer to someone who appreciates the Christian doctrine and the faith but has no personal commitment to the church, when asked I replied that I regarded myself as a ‘seeker’ (mudaoyou). This term is used in Chinese, both among Christians and more generally, to refer to someone who is keen to learn about a religion but has not yet converted to it. . . .

In October 2011, I attended a closed men’s retreat held by a Chinese American fellowship. When sharing testimonies, my emotions spun out of control and I burst into tears. Since that time, I have become more aware of the dangers of becoming profoundly involved in religious experiences and reminded myself from time to time of my role as a researcher rather than a believer.

However, precisely because of this unexpected episode, I caught the attention of the leader who believed that I would accept Jesus soon. Even though I did not convert, I did become more popular and credible among members of that fellowship, a step that greatly facilitated my investigation.

- Andrew T. Kaiser: Encountering China: The Evolution of Timothy Richard’s Missionary Thought, 1870 – 1891 (Pickwick Publication, 2019)

“Welsh Baptist missionary to China Timothy Richard (1845 – 1919) was once widely regarded as “one of the greatest missionaries whom any branch of the church, whether Roman Catholic, Russian Orthodox or Protestant, has sent to China.”

“Welsh Baptist missionary to China Timothy Richard (1845 – 1919) was once widely regarded as “one of the greatest missionaries whom any branch of the church, whether Roman Catholic, Russian Orthodox or Protestant, has sent to China.”

“Today, few have heard of Richard and his remarkable lifetime of ministry in China. As the first critical examination of Richard’s missionary identity, this groundbreaking historical study traces the narrative of Richard’s early life in Wales and his formative first two decades of service in China.

“Richard’s adaptations to the common evangelistic techniques of his day, his interest in learning from grassroots Chinese sectarian religions, his integration of evangelism and famine relief during the North China Famine (1876-79), his strategic decision to evangelize Chinese elites and his complicated relationships with Hudson Taylor and other China missionaries are all explored through the writings and personal letters of Richard and his contemporaries.

“The resulting portrait represents a significant revision to existing interpretations of this influential China missionary, emphasizing his deep empathy for the people of China and his abiding evangelical identity. Readable and relevant, Encountering China provides a new generation with an introduction to this lost legend of China mission.

“Andrew Kaiser (PhD, University of Edinburgh) has been living and working in China with his wife and two daughters since 1997. Andrew’s writings focus on the history of Christianity in China. When not in the archives, Andrew works as a public relations manager for a foreign company working in China. Over the years, he has assisted many different foreign companies and organizations negotiate the unique cultural, linguistic and legal challenges of working in China.”

For an insightful review of Encountering China go here; Kaiser responded here.

- Arthur Lin: The History of Christian Missions in Guangxi, China (Pickwick Publications, 2020)

“The History of Christian Missions in Guangxi, China describes the fascinating history of Catholic and Protestant missions in bandit-infested Guangxi from the 17th century to the present. Included is an overview of Guangxi’s historical context and its development throughout the 20th century. Particular attention is given to the missionaries through abundant quotations and several short biographies.”

“The History of Christian Missions in Guangxi, China describes the fascinating history of Catholic and Protestant missions in bandit-infested Guangxi from the 17th century to the present. Included is an overview of Guangxi’s historical context and its development throughout the 20th century. Particular attention is given to the missionaries through abundant quotations and several short biographies.”

Particularly affecting are glimpses into the lives of missionary families, whose lives were far from easy. For example, Walter Oldfield, who was born in Ontario in 1879. After losing his fiance to pneumonia, he married Mabel Dimock Sherman, whose husband had died in Guangxi just a month after their wedding:

Over the next five years, Mrs. Oldfield bore two children, Mildred and Ernest. The kids both battled sickness and at various times, one or both contracted (and survived) bronchial pneumonia, dysentery, malaria, whooping cough and German measles.

Around 1920 the family moved to the more remote northwest region of Guangxi, where the devastating Taiping Rebellion (1850 – 1864) had begun. They described their dwelling place as “the Black Hole of Kingyuen”:

In 1922, Mr. Oldfield was kidnapped, robbed and marched into the mountains. However, when some local soldiers made his captors scurry, he managed to escape. [By 1932 he had been attacked by robbers at least half a dozen times.]

Mr. Oldfield was at times called upon to serve as a peacemaker for the warring factions in Guangxi. On one occasion, he was presented with a gold medal for his role in negotiating with the enemy forces who had besieged Liuzhou. By risking his own life, hundreds of Liuzhou residents were spared. . . .

Guangxi’s mountainous landscape introduced another physical challenge. The mountains manifested God’s splendor, but they also presented a great obstacle. Oldfield personally experienced the challenge of the mountains when he took pioneer trips into the ‘neglected territories.’ He completed journeys of 300, 335, 700, 800 and 2,000 miles.

The Oldfields lived in Guangxi for almost 40 years, over six terms. He was honoured with a fellowship by the Royal Geographic Society of London and ended up as chair of the South China Mission.

- Chandra Mallampalli: South Asia’s Christians: Between Hindu and Muslim (Oxford University Press, 2023)

“South Asia is home to more than a billion Hindus and half a billion Muslims. But the region is also home to substantial Christian communities, some dating almost to the earliest days of the faith.

“South Asia is home to more than a billion Hindus and half a billion Muslims. But the region is also home to substantial Christian communities, some dating almost to the earliest days of the faith.

“The stories of South Asia’s Christians are vital for understanding the shifting contours of World Christianity, precisely because of their history of interaction with members of these other religious traditions. In this broad, accessible overview of South Asian Christianity, Chandra Mallampalli shows how the faith has been shaped by Christians’ location between Hindus and Muslims.

“Mallampalli begins South Asia’s Christians with a discussion of South India’s ancient Thomas Christian tradition, which interacted with West Asia’s Persian Christians and thrived for centuries alongside their Hindu and Muslim neighbours.

“He then underscores efforts of Roman Catholic and Protestant missionaries to understand South Asian societies for purposes of conversion. The publication of books and tracts about other religions, interreligious debates and aggressive preaching were central to these endeavours, but rarely succeeded at yielding converts.

“Instead, they played an important role in producing a climate of religious competition, which ultimately marginalized Christians in Hindu-, Muslim- and Buddhist-majority countries of post-colonial South Asia.

“Ironically, the greatest response to Christianity came from poor and oppressed Dalit (formerly “untouchable”) and tribal communities who were largely indifferent to missionary rhetoric. Their mass conversions, poetry, theology and embrace of Pentecostalism are essential for understanding South Asian Christianity and its place within World Christianity today.”