With Mission Fest coming up quickly (February 15 – 17 at Westside Church) I am posting a series on Christianity as a missionary religion:

With Mission Fest coming up quickly (February 15 – 17 at Westside Church) I am posting a series on Christianity as a missionary religion:

1. History of Missions

2. State of World Christianity

3. Specific Areas: Africa

4. Specific Areas: Asia

5. Specific Areas: Latin America

6. Not So Good News

7. New Approaches to Missions

I will look mainly at some of the new books covering these various areas, but will also try to cover a few key themes along the way. It probably goes without saying that I will just scratch the surface of each topic – but I do hope that people will go on to read some of the books, which are of high quality.

I. History of Missions

A good place to start is with The Missionary Movement from the West (Eerdmans, 2023), a book which presents the thoughts of leading missions scholar Andrew F. Walls. He passed away in 2021; this book was edited with loving care by fellow Scotland-based professor Brian Stanley.

When we think of the missionary movement, we generally think of what has taken place over the past few hundred years (particularly the past couple of hundred years) as Europeans and then Americans extended their influence around the world. That (especially the role of Anglophone Protestants) is Walls’ main focus; many of the other books look at other missionaries throughout history and, increasingly from the Global South.

But Walls states that the movement carries on; the subtitle is ‘A Biography from Birth to Old Age’ (not Death). He writes:

We have not reached the end of the missionary movement from the West, but it is no longer central to the evangelization of the world, the motive that brought it into being. . . .

I am old enough to know and to value the fact that there are still useful functions that the elderly can perform. But it was not my task in the lectures that gave rise to this book. Their function was to exercise another faculty of old age: retrospection, the long look back.

A key theme – essential in this time, when everything Western is often deemed colonial – is distinguishing between two models of Christian expansion.

While discussing “European Christendom’s encounters with Muslims and Jews,’ he does say, “In principle, Christendom had no place for plurality.” The date of 1492 is significant, he added, because Christendom reached its completion, with the forced conversion or expulsion of all non-Christians and as the height of cultural interaction “with the languages and thought of Europe.”

But he adds:

The crusading mode and the missionary mode are sharply differing methods of extending the Christian faith. They grew up in the same areas in the same period; they coexisted and went on side by side. But they are totally different in concept and spirit. The crusader may invite, but in the end, he is prepared to compel. The missionary cannot compel; the missionary can only demonstrate, explain, entreat – and leave the rest to God.

The crusader mentality was dominant in Latin America, but “in most of Africa, and still more in Asia, crusade was out of the question.”

Business interests did not view William Carey’s work favourably: “Under the British East India Company, it was clear policy that religion must never interfere with business.”

He adds:

The religious effects of the great European migration were thus mixed. The strangest aspect of all was in the position of Christianity. When the great European migration began in the 16th century, Christianity was the religion of Europe and a largely European religion.

By the end of the 20th century, a massive recession in the West, especially in Europe, and a massive accession in the rest of the world, especially in Africa, had transformed the cultural and demographic distribution of Christianity.

Christianity had become once more, as in its beginnings, a non-Western religion; and though it was by no means the only cause of the change, the missionary movement, the despised, semidetached appendix to the great European migration, had played a significant part.

. . . These events are the seeds of the destruction of Christendom and the beginnings of European secularization. . . . A wedge had been driven between the religious profession of the European nations and their political, economic and strategic interests. [Those] interests would inhibit the European powers from active propagation of Christianity in the lands beyond Europe, and sometimes led them to the active support of other religions. . . .

The fundamental difference between the crusader and the missionary is that the missionary lives and works on someone else’s terms. Though the colonial period brought all sorts of modifications, the generalization remains broadly true even today.

Walls explains that the missionary movement began in Catholic southern Europe; “it took Protestants another couple of centuries to develop a parallel infrastructure.” Though he focuses primarily on the Protestant missionary movement, he says:

Protestants cannot afford to neglect the Catholic story, for all that the Protestants were later to discover – all the issues about evangelization, inculturation, identification, ethnicity, human relations and relations with Caesar – were faced by the Catholic missions of the 16th century. . . . The missionary movement from the West is a single story in which Catholics and Protestants are inextricably linked.

The book is not primarily about generalities. One will read about William Carey, widely recognized as ‘the father of modern missions,’ but also that Pietist missionaries settled in India 100 years before he did. About Hudson Taylor, but also about other key missionary figures in China such as Robert Morrison, James Legge and Karl Ludvig Reichelt – and how “China got into the missionaries,” just as the “missionaries got into China.”

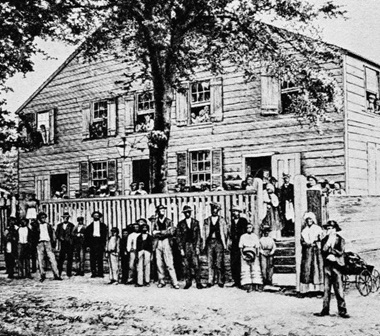

David George’s parents were taken as slaves from Africa to a plantation in Virginia. After running away, he was converted at Silver Bluff Baptist Churchm (above) in South Carolina. He eventually established several churches in Nova Scotia before he and other leaders and their families travelled to Sierra Leone, where he created the first West African Baptist church in Freetown. Go here for more: https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/george-david-1742-1810/

And Christianity in Africa. For example, “In 1792, 1,131 Africans from Nova Scotia marched ashore in Freetown, Sierra Leone . . . . In the second half of the 19th century [the church of Sierra Leone] would produce more missionaries per head of population than any other nation has ever done.”

Further on, Wall writes: “Africans have come to faith in ever-increasing numbers since the dismantling of the empires.”

One other key antidote to mistaken views about missionaries is Walls’ description of the “three legacies of evangelical humanitarianism”:

First, the Protestant missionary movement grew up with the antislavery movement and was often supported by the same people. So while the missionary message called for those overseas to experience evangelical conversion, it also was addressed to the reform of society, to issues that these days would be called human rights: slavery, infanticide and war. . . .

A second consequence was the outcome of [William] Wilberforce’s combination of political conservatism with moral radicalism, the seriousness of purpose characteristic of the evangelical. . . .

The third consequence arises from the way in which evangelicals understood conversion as an inner spiritual transformation evidenced by a radical outward change in behaviour. The missionary movement was the child of the evangelical movement.

In a touching moment, Walls wrote, “Let me take you to my own country,” where he points to the William Carey Memorial Church (now a Hindu temple), and a formerly imposing church “where a succession of Scottish preachers held large congregations spellbound.” And more, up and down the street. His conclusion:

The country that once sent out more missionaries than any other has become a desert, desperately in need of the gospel – not a revival, it is too late for that, but primary evangelism, cross-cultural evangelism, for our culture is now a non-Christian one.

The Missionary Movement from the West is, apparently, the final book in an impressive Eerdmans series – Studies in the History of Christian Missions – edited by Brian Stanley and Robert Frykenberg.

Recent books

Missions and missionaries don’t receive much attention in the church these days. But fortunately a good number of writers and publishers are beginning to take up the slack. May their work receive the attention it deserves. Here are some more recent books dealing with the history of missions.

- Markus Friedrich: The Jesuits: A History (Princeton University Press, 2022)

Speaking of Christians from the Global South returning to Europe, Pope Francis is notable in large part because he comes from Argentina. He’s also the first Jesuit pope.

Speaking of Christians from the Global South returning to Europe, Pope Francis is notable in large part because he comes from Argentina. He’s also the first Jesuit pope.

The Jesuit story is a long and complex one, since its founding by Ignatius of Loyola in 1540, so this 854-page book is not primarily about missions. However, Friedrich devotes almost 150 pages of The Jesuits: A History to ‘The Global Society.’ Names such as Matteo Ricci and Francis Xavier are well known; others are not.

Friedrich wrote about what the Jesuits actually did overseas:

On the one hand, the Jesuits ministered to the colonists; on the other, they worked to Christianize the indigenous population. These were very different remits: the one revolved around working in, with and for the incipient colonial societies and was concentrated mainly in the major cities overseas – Mexico City, Lima, Goa, Manila. The Jesuits there soon lived in conditions modeled on those in Europe. The other was the mission, which often took them far from the European colonial centers.

He points out that working with the two groups sometimes created tension. As did interaction with other Catholic missionary societies. And even more with Protestants:

In some cases, the Jesuits became active in certain missionary territories just to beat their confessional competitors to the punch. The Jesuit missionaries’ confident self-preservation sometimes had a blatantly anti-Protestant edge. . . .

But sometimes they cooperated as well: “Well, they do good to many natives whom we could not reach; anyhow it is better to have them as friends than enemies,” said Jules Torrend (1861 – 1936), a Jesuit missionary on the Zambesi, summarizing his attitude toward the Protestants. “In faraway and exotic locales, European solidarity and confessional quarrels did not stand in a fixed hierarchy.”

As a review in Church Times states: “Friedrich notes that ‘Ignatius founded his order in an age of profound change for Europe.’ He acknowledges that a history of the Jesuits has to be ‘essentially a world history in a nutshell.'”

- Alice T. Ott: Turning Points in the Expansion of Christianity (Baker Academic, 2021)

Alice Ott surveys the history of missions by telling the story of pivotal turning points in the expansion of Christianity. She examines 12 key points in the growth of Christianity, from the Jerusalem Council to Lausanne ’74:

Alice Ott surveys the history of missions by telling the story of pivotal turning points in the expansion of Christianity. She examines 12 key points in the growth of Christianity, from the Jerusalem Council to Lausanne ’74:

1. Embracing Ethnic Diversity: The Jerusalem Council (49)

2. Pushing beyond the Boundaries of Empire: Patrick and the Conversion of Ireland (ca. 450)

3. Expanding Eastward: The East Syrian Mission to China (635)

4. Confronting Pagan Gods: Boniface and the Oak of Thor (723)

5. Accommodating Culture: Jesuits and the Chinese Rites Controversy (1707)

6. Pioneering a Global Outreach: Zinzendorf and Moravian Missions (1732)

7. Launching a Mission Movement: William Carey and the Baptist Missionary Society (1792)

8. Breaking the Chains of Sin and Slavery: British Abolitionism and Mission to Africa (1807)

9. Empowering Indigenous Churches: Henry Venn and Three-Self Theory (1841)

10. Converting the Lost in the Era of Imperialism: The Scramble for Africa (1880)

11. Debating the Meaning of Mission: The Edinburgh World Missionary Conference (1910)

12. Reaching Missional Maturity: Lausanne ’74 and Majority World Missions (1974)

Ott was interviewed by Christianity Today about Turning Points in the Expansion of Christianity. She explains why some of the lesser known names and movements are included, and also discusses some that are better known.

Christianity Today: The 1974 Lausanne Conference may be the turning point that resonates most with readers –perhaps because it is the most recent. What do you find most significant about it?

Alice Ott: A key goal of Billy Graham and the steering committee of the Lausanne Conference was reaffirming an evangelical foundation for mission. But another important aspect is that Lausanne ’74 reflected evangelicalism’s increasingly multicultural, global identity. While evangelicalism today is sometimes barely holding its own in the West, it is exploding in many parts of Africa, Latin America, and Asia. And missionaries are flowing to and from every continent.

Lausanne ’74 also inspired and furthered the growth of mission movements in many important non-Western countries. In the book, I focus on Nigeria, South Korea and Brazil, all of which have large numbers of cross-cultural missionaries today. Brazil, for example, has more foreign missionaries than any country except the United States.

It is worth noting that the fourth Lausanne Congress (Seoul 2024) will take place this September, following up on Lausanne 1974, Manila 1989 and Cape Town 2010 (which I attended; it was impressive).

- Edward L. Smither: Christian Mission: A Concise Global History (Lexham Press, 2019)

- F. Lionel Young III: World Christianity and the Unfinished Task (Cascade Books, 2021)

- Timothy C. Tennent: How God Saves the World (Seedbed, 2017)

These three books are good brief introductions to missions and missionaries, going from the longest (Christ Among the Nations) at 219 pages to the shortest (How God Saves the World) at 124.

Edward Smither, a professor and dean of intercultural studies at Columbia International University, starts out strong in Christian Mission:

Edward Smither, a professor and dean of intercultural studies at Columbia International University, starts out strong in Christian Mission:

George Liele (c. 1750 – 1820) was America’s first cross-cultural missionary. He arrived on the shores of Jamaica in 1783 to live, work and ultimately pioneer Baptist mission work on the island. Born a slave in Virginia, Liele received his freedom . . . Fearing that he would be enslaved again he sold himself as an indentured servant to Jamaica. . . .

This book is about the George Lieles in history – innovators in mission who sacrificially went to the nations to make known the gospel of Christ.

Growing up, Smith assumed mission work occurred in places such as Africa or Haiti. Now he says: “While mission definitely involves crossing borders, the greatest boundary that a missionary navigates is the one between faith and non-faith.”

World Christianity and the Unfinished Task has some strong endorsements, including that of Brian Stanley, who said:

World Christianity and the Unfinished Task has some strong endorsements, including that of Brian Stanley, who said:

The extraordinary transformation in the global composition and cultural flavor of Christianity that has taken place in the last half-century have attracted the attention of numerous scholars, but sadly have yet to penetrate the consciousness of the average churchgoer in the West. Lionel Young’s readable and stimulating survey will surely help to address that deficit, widening horizons and dispelling preconceptions.

Among the other fans is David Bebbington, the University of Stirling professor best known for his definition of evangelicalism, referred to as the Bebbington quadrilateral.

In the Foreword, Muthuraj Swamy wrote:

[Lionel Young] invites Christians, particularly those in the West, many of whom have long neglected the story of World Christianity, to be mindful of the many Christianities that exist, particularly in the Global South.

In the first chapter, Young writes about his own efforts to educate even the educated, who often assume that Christianity fell into decline after Africans gained their independence.:

After a long day of study in Cambridge I usually walk to an old pub across from Magdalene College where C.S. Lewis would often repair for a pint with a colleague. . . .

[In dozens of conversations] I’ve now become accustomed to the audible gasps in the room when I tell people that there are nearly three times as many Christians on the African continent than in the United States, Canada and Greenland combined!

(I spoke with Muthuraj Swamy, Director of the Cambridge Centre of Christianity Worldwide – where he and Young are colleagues – last fall, while we were in Cambridge, and mentioned him in a piece I wrote about our trip, right at the end.)

How God Saves the World is short and sweet. Timothy Tennent has decided to create “a play in three acts”:

is short and sweet. Timothy Tennent has decided to create “a play in three acts”:

- Act One: Seven Turning Points in the History of Missions Before 1792

- Act Two: The Great Century of Missions, 1792 – 1910

- Act Three: The Flowering of World Christianity, 1910 – present

He tells many good stories. One I particularly enjoyed echoes Andrew Walls’ crusader / missionary distinction. Tennent wrote:

It is important to realize that the Crusades are not the only story of the Christian response to Islam during the Middle Ages. The fourth historical focus highlights the life and ministry of Raymond Lull (1232 – 1315), known as the ‘Father of Islamic Apologetics.’ . . .

Lull insisted that everyone trained in his method be willing to suffer for the sake of the gospel. Given the ongoing conflicts with Islam in his day, this was a sober realization by Lull of the inherent dangers in any Islamic mission.

Lull made at least four missionary journeys to Islamic North Africa. He was able to present his apologetic defense of Christianity to Muslim leaders. However, he also suffered expulsions, abuse and long imprisonments. Finally, when he was in his eighties, he preached to a gathering of Muslims in Algiers and was stoned to death.

How God Saves the World would be ideal for Bible study or other groups. It’s short, easy to read – and reasonably priced. Discounts increase for groups of 10, 20, 50 and 100; go here to order.

I’m running out of time and space, so I’ll simply list a few other books, with brief write-ups from the publishers:

- Dyron B. Daughrity: A Worldly Christian: The Life and Times of Stephen Neill (The Lutterworth Press, 2021)

Bishop Stephen Neill was one of the most prolific, accomplished and fascinating Christian leaders of the global church in the 20th century. Privileged to live in radically different cultural contexts over the course of his life, Neill was also a supremely gifted individual.

Bishop Stephen Neill was one of the most prolific, accomplished and fascinating Christian leaders of the global church in the 20th century. Privileged to live in radically different cultural contexts over the course of his life, Neill was also a supremely gifted individual.

The subject of A Worldly Christian excelled by turns as a missionary, a bishop, an ecumenist, a professor and a prolific author, all the while travelling around the world to share his tremendous knowledge of the world Christian movement with scholars, clergy and laypersons alike.

(I was fortunate enough to study Neill’s A History of Christian Missions with Don Lewis at Regent College decades ago; it really opened my eyes.)

- D.C. Keane: Uncharted Mission: Going to the Final Frontiers (William Carey, 2021)

“Lord, why another mission agency? There are already so many good ones,” Greg Livingstone cried out on a beach in 1983. But, as he made his case to God that He should find someone else to change the world, the answer became clear: the world needed a new agency, operating in a new way, that would focus entirely on all Muslim peoples.

So began the wild, risky, worthy story told in Uncharted Mission, a book that is more than the history of the founding of Frontiers. D. C. Keane weaves together interviews with over 100 missionaries who refused to accept the status quo in missions and were willing to go where no one had gone before – to the Muslim frontiers. In this inspiring true story, you’ll meet pastors, engineers, artists, pilots and others whose lives changed course when they discovered that Muslims were largely left out of historic missionary efforts.

- Sarita Gallagher Edwards, Robert L. Gallagher, Paul W. Lewis, DeLonn L. Rance: Christ Among the Nations: Narratives of Transformation in Global Mission (Orbis Books, 2021)

“In Christ Among the Nations, the living Jesus is made present by the Holy Spirit to the world as savior, empowerer, healer and hope. These themes situate the mission of God to save the world amid the narratives of scripture, the church and contemporary missiological endeavors. Thanks to our four Pentecostal authors whose testimonial weaving together of these materials invites our own participation in the redemptive work of God.” – Amos Yong, Dean of the School of Mission & Theology, Fuller Seminary

“This collection is a much-needed, challenging and scholarly addition to contemporary missiological literature, particularly as it gets to the heart of Pentecostal and Charismatic narratives in their praxis of mission. A must-read!” – Allan H. Anderson, emeritus professor of mission and Pentecostal studies, University of Birmingham, UK

“This book will be invaluable for everyone who wishes to understand Christ’s work among the nations – it is a significant contribution to contemporary mission studies, offering unique insights into global mission.” – Julie Ma, professor of missions and intercultural studies, Oral Roberts University

- Christopher J.H. Wright: The Great Story and the Great Commission (Baker Academic, 2023)

Christopher Wright encourages us to explore the Bible’s grand narrative and to bring the whole counsel of God in Scripture to our understanding of who we are and what we must do as God’s people.

Christopher Wright encourages us to explore the Bible’s grand narrative and to bring the whole counsel of God in Scripture to our understanding of who we are and what we must do as God’s people.

In The Great Story and the Great Commission, he helps us understand mission in its broadest sense, including our creational responsibilities, by exploring the question, “How does our purposeful activity as God’s people in God’s world reflect the breadth of God’s own intentions for his whole creation and all nations?”

Wright’s goal is to get readers excited about the dramatic vista of the whole Bible and to help them understand the breadth and depth of missional engagement that they are called to live as actors in that drama.

- Tim Keesee: A Company of Heroes: Portraits from the Gospel’s Global Advance (Crossway, 2019)

Across the globe, the gospel is advancing through the work of Christians willing to risk everything in the hardest places. A Company of Heroes, written by a missions journalist as he traveled throughout 20 different countries, is filled with stories of Christians past and present whose examples of endurance, courage, sacrifice and humility connect readers with God’s unstoppable work across the world. These heroes are simply ordinary people who have experienced the transformative power of a Savior who is alive and moving – and their stories will inspire readers to take faith-filled risks for the gospel.

There are so many fascinating missionary figures – Hudson Taylor and Lottie Moon in China, David Livingstone and Mary Slessor in Africa . . . the list goes on. Faith Today (January/February 2024) posted an article about ‘Five missionaries we should know from the past 175 years.’

Part II next week.

Thank you for taking on this big subject Flyn. This was a great start, and I am looking forward to the rest of your series. There is so much confusion about missionaries, missional churches and the mission of God these days. Thank you for helping bring some clarity.