Armenia’s Christian culture remains strong, despite centuries of Muslim pressure and persecution.

My wife Margaret and I just returned from a month-long trip. Over the next four weeks I will describe some of the sites, cultures and experiences which made a particularly strong impression upon us.

For the most part – especially in Georgia, Malta and England – I will focus primarily on people we met, often with some kind of connection to Vancouver.

But our first stop was Armenia, and there it was the enduring strength of the culture and the resilience of the people that particularly impressed us.

Armenia is the first nation to embrace Christianity. That commitment is still evident as a source of shared identity and solace throughout the country, but it has also been a source of suffering as the people clung to their faith in a region dominated by Islam.

Reduced, but not destroyed

Mount Ararat, so important to Armenian identity – and so close to Yerevan – is now in Turkey.

Just over 100 years ago, Armenian culture was well established in large sections of eastern Turkey and stretched all the way across to the Caspian Sea. Intense persecution by the Turkish government, exacerbated by Soviet control during most of the 20th century have caused tremendous dislocation.

There are now millions of Armenians living abroad. The three million or so who remain are now concentrated in the landlocked Republic of Armenia, which is located south of Russia between, but not touching, the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea.

Armenia has an ancient, but unstable, history. As Benjamin Braude said in Christians & Jews in the Ottoman Empire:

The Armenians have been caught in the middle of every struggle in near eastern history, and more often than not have chosen, or had chosen for them, the losing side. At one time or another, the Greeks, the Persians, the Arabs, the Mongols, the Russians and the Turks have invaded their lands. Periods of Armenian independence have been brief and distant.

Armenia was under the control of the Ottoman Empire for several centuries, until the early 1900s. Braude noted:

Tragically for the Armenians, their hopes for national independence arose at the end of a century-long succession of Christian uprisings in the Balkans [also controlled by the Ottomans]. And their aspirations were centred in Anatolian territory that the leaders of the Ottoman Empire in its last decades came to regard as the last bastion of what remained of their empire. . . .

To a much greater degree than other Christian peoples, the Armenians were integrated with the Muslim population. Their misfortune was that in the past centuries they had got along well enough with Kurds and Turks to inhabit some of the same towns and villages. No compact minority begging partition, they shared much of eastern and southern Anatolia with their Muslim neighbours.

The Armenians were considered an obstacle as Turks created their nation state. Hundreds of thousands were killed during the Hamidian Massacres of 1894 – 1896, and as many as 1.5 million during the the Armenian Genocide which began in 1915.

Turkey, and many other nations still do not accept the reality of the Armenian Genocide. In 2005, the International Association of Genocide Scholars responded to the call by Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan for an “impartial study by historians” concerning the fate of the Armenian people in the Ottoman Empire during World War I.

In part, their letter stated:

On April 24, 1915, under cover of World War I, the Young Turk government of the Ottoman Empire began a systematic genocide of its Armenian citizens – an unarmed Christian minority population. More than a million Armenians were exterminated through direct killing, starvation, torture and forced death marches. The rest of the Armenian population fled into permanent exile. Thus an ancient civilization was expunged from its homeland of 2,500 years.

Expunged from Turkey, but still thriving in Armenia – and now hosting an impressive testament to that violent time.

Armenian Genocide Memorial & Museum

The Armenian Genocide Memorial.

Several Armenians asked us, “Why are you here?” – not in a challenging way, but because they don’t see too many (non-Armenian) visitors from North America.

But they are also used to being overlooked. The most egregious example of has been the century-long minimization of the Armenia Genocide.

Some from Vancouver will have visited Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem. Armenia has a counterpart in its capital Yerevan, the Armenian Genocide Memorial & Museum. Both are impressive, and bear eloquent witness to the reality and intent of mass slaughter.

One of the museum’s early displays sets the stage:

Towards the middle of the 11th century nomadic Seljuk Turkic tribes conquered Asia Minor and Armenia. Subsequently, the Turkish principalities that had appeared in Asia Minor were replaced by Ottoman Turks. Shortly thereafter Ottomans conquered Constantinople in 1453, and the Byzantine Empire ceased to exist. The wide Ottoman Empire was created as a result of successive conquests.

Throughout its existence the Ottoman Empire fed on violence (mass murder, forced Islamization, ‘human taxation,’ looting) upon its Christian subjects, including Armenians.

The Ottoman Turks considered themselves leaders in the struggle against infidels and treated the Christians with particular cruelty. The gavur, or infidel, who dared resistance was to be ended. The punitive expeditions, whether structured or sporadic, were instrumental in maintaining the unity of the empire and resolving domestic issues.

The first attempt at mass destruction of Armenians took place in 1725, when Sultan Ahmed III (1703 – 1730), encountering the resistance of Armenians in Syunik and Artsakh regions, gave orders to exterminate the Armenians of both regions with the accusation that they blocked access of the Turkish Army to the Caspian Sea.

To meet the increasing demand of their Janissary troops in manpower, the Turks levied a special tax, devshirme (blood tax), which required forced collection and Islamization of Christian children. This cruel tradition began during the reign of Murad I (1362 – 1389) and went on to the beginning of the 19th century. . . .

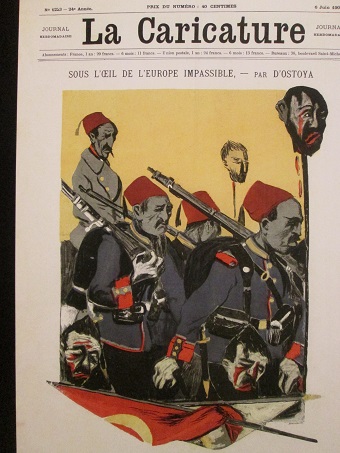

Caption: “‘In front of Europe’s impassive eye.’ This caricature on the front page of the French satirical magazine hints at continuous Turkish atrocities and European diplomacy which left that violence unanswered.”

Another display describes the immediate background to the Armenian Genocide:

After coming to power in 1908, the Young Turk party leadership espoused the idea that the “salvation of the Turkish homeland” could be achieved only through the liquidation of the empire’s Christian population. The 4th Congress of the party in autumn 1911 confirmed the necessity of Islamizing the population. This called for forced Turkification and, if it failed, extermination of the Christians.

Based on the decisions of the Congress, the central committee of the party developed a plan of action for the annihilation of the Armenian population, followed by other Christians of the empire. The plan called for the deportation of Armenians from Western Armenia [eastern Turkey] to the desert zones of central vilayets [provinces], and their destruction along the deportation routes and in concentration camps.

The next steps of the Young Turk government were geared toward the realization of the decision to exterminate the Armenians. Anti-Armenian actions increased sharply in 1912-14; unpunished killings and violence were common occurrences in Armenian-inhabited areas. Local Young Turk party structures were engaged in blatant anti-Armenian propaganda. Political figures with former experience in Armenian massacres were appointed to government offices in the Armenian provinces.

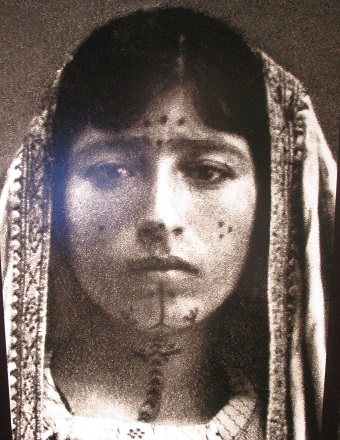

Caption: “Loutfie Bilemdjian, 17 years old, born in Aintab, 1909, rescued from Muslim captivity in 1926.”

The resettlement of muhajirs (Muslim refugees from the Balkans) in Western Armenia and Armenian-populated town and villages resumed in 1913. That was further proof of the Young Turk strategy to emulate Sultan Abdul Hamid’s traditional policy of changing the demographic picture of Armenian provinces of the Ottoman Empire.

The significant economic, educational and cultural awakening and progress, as well as modernization of Western Armenia society brought about hatred and intolerance among the Muslim population. The Christian population, Armenians among them, were blamed for the Turkish losses in the Tripolitanian (1911-12) and Balkan (1912-13) Wars. They were taken as scapegoats and accused of treason.

Young Turks were waiting for a suitable opportunity to implement their decisions. World War I was regarded as such a chance.

We learned a lot during our tour of the museum – and were glad to learn that our nation is actively supporting the Armenian people.

Canadian policy

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau visited the Armenian Genocide Memorial Complex, accompanied by Armenia’s Minister of Foreign Affairs and several other officials.

We discovered when we arrived in Armenia that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau had been in Yerevan just a couple of days before us, participating in the summit of la Francophonie. While there he visited the Armenian Genocide Memorial & Museum.

This comment is from their site:

The Prime Minister of Canada Justin Trudeau . . . laid a wreath at the Memorial, and with the members of delegation put flowers at the eternal fire honouring the memory of the innocent martyrs of the genocide.

[He] also visited the Armenian Genocide Museum, and got acquainted with the museum exhibits and documents about the Armenian Genocide. After a guided-tour at the museum, Justin Trudeau left a note in the Memory Book of the Museum: “Today we remember the victims of the Armenian Genocide and solemnly swear not to let history repeat.” . . .

The guests from Canada also made a tour in the Memory Alley, where the Prime Minister planted a silver fir.

In 1996 Canada adopted a resolution condemning the Genocide. On June 13, 2002, the Canadian Senate recognized the Armenian Genocide and condemned any attempt to deny or distort the historical truth and call it by any other word than genocide. In Canada April 24 is the Day of Remembrance of 1.5 million Armenian victims of the 20th century first genocide. In 2004 the House of Commons of Canada recognized the Armenian Genocide committed by the Ottoman Turkey.

It is encouraging to see our Prime Minister take the genocide seriously; one hopes it will go some way to reversing Turkey’s ongoing attempts to cover up the atrocities carried out by their forbears. Only 29 nations officially recognize the Armenian Genocide.

Lessons learned?

With so many examples of Muslim nations and movements persecuting Christians (and others) around the world right now, lessons from the Armenian Genocide are still very relevant. Think of three situations which are often in the news at the moment – the unjust treatment of Asia Bibi by the Pakistan’s court system and citizens; the ongoing massacres in northern Nigeria; and the Saudi-sanctioned murder of Jamal Khashoggi (ironically, in Turkey).

What should our response be to these and other outrages? Prayer is a good start. Christians all over the world took part in the International Day of Prayer for the Persecuted Church earlier this month. There is some coverage in the western press, though not nearly enough, of these human rights abuses. There is some political condemnation, though again not enough.

And there is, of course, the response by the ‘leader of the free world’ (Donald Trump, that is) to the Khashoggi situation:

It could very well be that the crown prince had knowledge of this tragic event – maybe he did and maybe he didn’t! We may never know all of the facts surrounding the murder of Mr. Jamal Khashoggi. In any case, our relationship is with the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Writing in The Burning Tigris, Peter Balakian pointed out that while the Armenian Genocide is now often referred to as ‘the forgotten genocide,’ it once loomed large for Americans and Europeans:

The U.S. response to the Armenian crisis, which began in the 1890s and continued into the 1920s, was the first international human rights movement in American history and helped defined the nation’s emerging global identity.

[It is encouraging to see another of Balakian’s comments: “Much of America’s moral sentiment emanated from the near century of Protestant missionary presence in the Ottoman empire.”]

However, continued denial by the Turks and self-interest on the part of the Americans allowed the persecution to continue and then be largely forgotten. Balakian said:

Like the sultan, the Young Turks and then the Kemalists continued to deny and rationalize the Armenian Genocide. They planned the genocide and implemented it as covertly as they could, and when they were confronted by the world, they resorted to blaming the victim and rationalizing the crime, and they did everything they could to promote forgetting. . . .

The vehemence with which the new Turkish regime denied the Armenian Genocide, evident at the Lausanne Conference in 1922 . . . dovetailed with the dramatic shift in American policy toward Turkey and the Middle East, as the United States pursued an open door policy for the oil of Mesopotamia and a new dollar diplomacy.

Even today, the United States has not officially recognized the Armenian Genocide.

Life goes on

Coat of arms of Artsakh.

History is all around in Armenia, so it is easy to dwell on the past. We visited several beautiful church sites around the nation, each with centuries of memories surrounding it. But citizens (98 percent of who are actually Armenian, so it’s not a multicultural hotspot) are getting on with their lives. Yerevan is a bustling city, full of interesting sites and good food.

A particular highlight for me was a three day trip into the Republic of Artsakh (formerly known as Nagorno-Karabakh). In the 1990s it split from Azerbaijan in a war that cost up to 30,000 lives and displaced more than one million people in Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Its population is Armenian, it is a part of historic Armenia and there is easy access from Armenia, but no other nations officially recognize it as a state, including Armenia. A fascinating story in itself . . .

Great report, Flyn. Look forward to the others.