Peking Union Medical College is China’s top medical school and played a key role in fighting COVID-19.

Trump Card! Victory Belongs to China! Four Top Hospitals Join Forces in Battle for Wuhan

That headline in a Chinese newspaper referred to four hospitals leading the fight against COVID-19 – and a later article in China Christian Daily pointed out that each of those hospitals was initiated by missionaries:

‘Northern Union, Southern Xiangya, Eastern Cheeloo and Western Huaxi’ represent the highest level of Chinese medicine. They were once known as the four “hundred-year-old shops” among China’s medical education community . . . established by missionaries who introduced Western medicine in their treatment of Chinese patients.

It highlighted the eminence and role of the four hospitals:

Peking Union Medical College Hospital: “On January 26 of this year, the first group of medical staff from Peking Union Medical College Hospital set off to support the people of Wuhan.”

Peking Union Medical College Hospital: “On January 26 of this year, the first group of medical staff from Peking Union Medical College Hospital set off to support the people of Wuhan.”- Xingya Hospital, Hunan Province: “For nearly two decades, experts and medical care at Xiangya Hospital have been involved in the fight against SARS, influenza, Ebola and avian influenza.”

- Cheeloo (Qilu) Hospital, Shandong University: “On February 7 of this year, Li Yu, the captain of the fourth medical unit of Qilu Hospital, led 130 team members to the Wuhan Tianhe Airport.”

- West China Hospital, Sichuan University (Szechuan): “West China Medical Center, Sichuan University is now China’s largest comprehensive medical university.”

The article described the missionaries and mission societies that founded each hospital.

China appears to have weathered the worst of the coronavirus pandemic and is now sharing its medical knowledge internationally. While the adequacy of China’s response is widely contested, there is no doubt that its medical system has been completely transformed over the course of the past century – and that the transformation began under the direct influence of the missionary community.

A recent book provides a fascinating and timely glimpse into the life of the medical missionary who founded Peking Union Medical College Hospital.

Thomas Cochrane’s dream

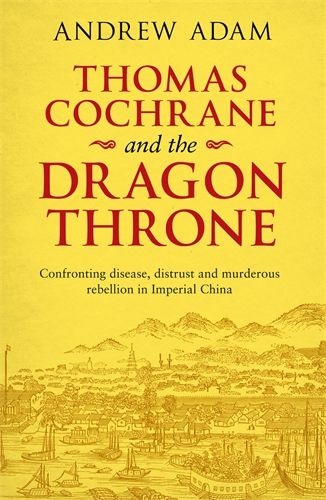

Thomas Cochrane and the Dragon Throne (SPCK, 2018) tells one of the larger-than-life stories that missionary biographies often supply. The subtitle, ‘Confronting disease, distrust and murderous rebellion in Imperial China,’ does not overstate the case.

Thomas Cochrane and the Dragon Throne (SPCK, 2018) tells one of the larger-than-life stories that missionary biographies often supply. The subtitle, ‘Confronting disease, distrust and murderous rebellion in Imperial China,’ does not overstate the case.

Cochrane was a poor boy from the docklands downriver from Glasgow who became a Christian during a D.L. Moody crusade. He worked hard to get through medical school so he could work in “the neediest place on earth.”

After serving for several years in a town on the border of China and Inner Mongolia, where he (with his wife and three very young children) survived several threats to his life, he was re-posted to Peking (now Beijing)

There he enlisted the help of the Empress Dowager and her highest courtiers as he founded China’s first medical college, which he then passed on to the Rockefeller Foundation so it could reach a higher potential.

Surviving the Boxers

Chaoyang was a shock to Tom and Grace Cochrane when they first arrived in 1897. The town was in the centre of ongoing clashes between factions as the Manchu dynasty weakened, with secret societies, warlords and bandits threatening. Cochrane housed his first medical dispensary in sheds built for livestock, by then home to rats.

Cochrane often visited surrounding villages:

More than once Tom was chased by brigands and only the strong walls of an inn saved him. Villagers were very curious, but often also suspicious and even hostile.

In time, he adapted to the culture and became increasingly well accepted:

When he was transformed into a kindly Chinese doctor in cap and gown with a pigtail down his back, the villagers welcomed him courteously and offered him tea and sweet pancakes.

The Cochranes had three boys while there (all of whom grew up to be doctors). They were joined by another missionary family, the Liddells – parents of the famous Olympic sprinter (Chariots of Fire) Eric Liddell, who eventually died in a Japanese prisoner of war camp in China, universally noted for his selfless service to other inmates.

Times were dangerous, and both families were forced to flee in 1900 during the Boxer Uprising, which arose out of China’s (largely justified) grievances against the West. Conditions were particularly perilous for missionaries, many of who lived unarmed and in vulnerable situations.

The Empress Dowager Cixi – “who was said to hate missionaries and to have told a diplomat’s wife, ‘They inoculate our people with the virus of Christianity'” – threw in her lot with the Boxers.

While the uprising was quelled relatively quickly – and the Empress Dowager managed to retain her role only by agreeing to pay large indemnities to the occupying imperial powers – 239 missionaries, mainly Protestants, were martyred, along with tens of thousands of Chinese converts.

Adventure stories

Boxer rebels

Missionary stories deserve to be read for many reasons, but many of them are simply rattling good yarns.

For example, when Cochrane finally fled from his home/clinic – having sent his family and the Liddells on ahead – he was shot at and then spent the night in a graveyard:

At dawn the sun rose like a huge red disc; it was going to be another scorching June day. Tom gathered his things and saddled the horse. It was tempting to linger in this quiet place but he must press on.

Suddenly a man emerged from behind a mound. Then another and another, until a score of them formed a circle around him. They had been camping in another part of the burial ground. Grasping swords and spears, they looked like figures from a Chinese opera. He saw the flash of scarlet scarves and knew they were Boxers. Was this how it would end, butchered in a graveyard, thousands of miles from home?

Then one of them stepped between him and the others. He said hoarsely, “I know this man. No one touches him except over my dead body.” He turned to Tom. “Go at once because I can’t protect you. Ride!”

Tom scrambled into the saddle and galloped away . . .

Actually, one publication – Sorted!, a men’s magazine which focuses on wholesome (often Christian) adventure, celebrity and other lively topics – did pick up on the story, launching in with this escape and then interviewing author Andrew Adam, Cochrane’s step-grandson, and himself a doctor.

Here is one portion:

Dr Adam initially wanted to tell Cochrane’s story because it rankled that the medical school, still thriving and now called the Peking Union Medical College, did not acknowledge that it was founded by a Western missionary – that didn’t fit in with the story the Chinese government wanted to tell, of interfering Western colonialists, who came simply to exploit. But Adam also discovered there was far, far more to Cochrane’s story.

“When I looked into it, I became intrigued by the wider story. I’m a retired pathologist, so I am fascinated by opium dens, eunuchs, concubines, body snatching, foot binding, poisoning and massacres. All of them feature in the book.”

Starting over in Peking

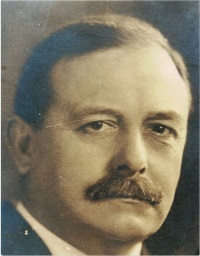

Dr. Thomas Cochrane (Cochrane family collection)

The London Missionary Society sent the young family back to Scotland to recover, but it wasn’t long before Cochrane was determined to return:

While others [at Glasgow Medical School and elsewhere] sang his praises, he shrugged them off, saying, “The Boxers chased me out and I hadn’t much to show for it.”

While still in Chaoyang, facing a constant onslaught of work, he had begun to dream of creating a medical training centre:

Like a good wife, Grace kept telling him there was no point in killing himself and that patients would always come back the next day; whatever he did was a drop in the torrent of their suffering. She was right. Tom estimated that across the Chinese Empire, 40,000 men and women perished every day, many of them suffering painful and avoidable deaths.

The death rate was like the Yangtze River in spate; you might pluck an occasional soul to safety, but in doing so you missed a hundred others. And all the time the river rose higher.

There had to be a better way to use his training and his skills. And so Tom’s dream was born, on a beaten mud floor with women squatting on their heels, babies wailing and tuberculous patients coughing up their souls. In those surroundings it could not have seemed less attainable.

It was to build a medical college and a teaching hospital, with facilities equal to the best in Britain or America. It would have a dedicated teaching staff and a scientific curriculum, taught in Chinese to Chinese students. Its medical degrees would be approved by the Imperial Government. At the same time – and this was essential – students would receive instruction in the Christian faith.

However, Cochrane’s dream didn’t seem much more attainable when arrived back in Peking October 31, 1901 – even though the Boxers had been defeated and he had been specifically commissioned by the London Missionary Society to rebuild their destroyed hospital and coordinate their medical and evangelistic work.

Most of his work was still with people on the margins:

The difference between Chaoyang and Peking, Tom concluded, was that in the former everyone was poor and struggling to survive; here the wealthy rode by dead bodies in the gutters without turning their heads. . . .

Soon Tom moved the would-be hospital into what had been a grain store:

He hung a signboard outside, and in no time beggars, peddlars and outcasts were queuing up, bringing with them all the parasites and pestilences of China. For them the stables were paradise, for they had nothing.

The first question to them was “Chi fan me la? (Have you eaten yet?),” which is a common form of greeting. Of course the answer was always no. He struggled to provide food out of a slender purse.

Cochrane jumped right back into his work, seeing some 20,000 patients each year. But his dream had not left him, and as he began work on the hospital, he sought God’s help:

From the top of the rubble, Tom saw in the distance the yellow roofs of temples and palaces in the Forbidden City, looking like gigantic upturned boats, rising among the trees. Somewhere beyond the gatehouses and ‘dragon bridges’ was the throne room, where the Empress sat at the centre of the world, wielding immense authority over millions of subjects.

Tom wrote later, “Under a sudden impulse, I prayed that God would somehow enable me to touch one of the oldest thrones in the world.”

That prayer was a bold one, but it was answered.

Answers to prayer

Chief Eunuch Li Lianying became an unlikely ally.

Through a dramatic accident (many would describe it as a miraculous encounter), Cochrane’s outreach to a key British administrator and a call from the Chinese community for his services during the Blue Plague (a cholera epidemic in 1902), his stock rose dramatically:

What a contrast with life in the mule stables! . . . His friendship with Prince Su [of the miraculous encounter] also opened up professional opportunities at court. Suspicion melted as Su’s family and friends confided in Tom about illnesses that had defeated their own doctors.

In time, he was called upon to provide healing to the eunuch community: “within the Forbidden City they ran the Celestial Palace and did all the manual work.” He became quite friendly with the chief eunuch, Li Lianying, who was extremely close with the Empress Dowager, and even met once with Cixi herself:

After having performed a particularly delicate operation on Li Lianying, and having gained his trust, Cochrane felt he could ask him to prevail up Cixi for financial support for the proposed hospital. Remarkably, that promise was made:

And so the Empress Dowager Cixi allowed the first western medical school to be built in Peking, in the knowledge that it was going to be built and run by missionaries. The irony is that five years earlier she would as gladly have let the Boxer chop their heads off.

Cixi not only approved the project, but donated the equivalent of £150,000 in 1903, which encouraged many other donors in China and Britain. Cochrane and a team from several missionary societies were on their way.

Rockefellers take over

Thomas and Grace Cochrane and their children with the Duke and Duchess of Te and their family. (Cochrane family collection)

The hospital opened in 1906, with eight British and America missionary doctors; by the next year they had a dozen. The first class of western-trained doctors graduated in 1911.

But while Cochrane had made major strides towards his goal, he was unable to realize it completely; the amount of money necessary was beyond his reach. The hospital was still not large and the college was faltering, needing money for bursaries, better furniture, a more complete library, etc.

As it turned out, there were saviours in waiting. John D. Rockefeller Sr. and his son – Baptists “who had long supported evangelists in Asia” – created a foundation “to promote the well-being of mankind throughout the world.”

They settled on Peking Union Medical College after touring China to check on potential sites.

Doctors graduating from Peking Union Medical College, Beijing (China), 1947

Cochrane wrestled with the offer of purchase:

Eventually he was reconciled to the change. To say he had no regrets would be wrong, but the dream of creating the finest medical school in China had stalled.

The Rockefellers had deep pockets; they could refinance the college on a scale that no one else could contemplate and thereby ensure its future.

There were downsides – the gospel would no longer be preached and teaching would be in English rather than Chinese, for example – but on the other hand, China would have a first-class medical complex. After assuming control in 1915, the Rockefeller Foundation would invest $45 million in the project.

Chinese achievements, missionary roots

Adam wrote Thomas Cochrane and the Dragon Throne at least partly to bring attention to role of missionaries in developing China’s medical system. But he puts it all in perspective with this comment:

The wheel of fortune takes strange turns. In the event it was not Christianity, the Rockefeller millions or modern science that redeemed the health of China. It was the political will of a Communist regime, enforced through harsh ideological discipline. In a few years, it achieved more than all the emperors, missionaries, philanthropists, scientists and reformers put together.

An army of ‘barefoot doctors’ was trained in basic hygiene, and it marched out to educate the nation, at gunpoint if necessary, village by village and street by street. The people were forced to cleanse their environment and to wage war on the myriads of vectors which allowed diseases to flourish: flies, mosquitoes, fleas, lice, ticks, bedbugs, worms, snails and animals. The same hard-line approach was used to suppress the use of opium.

That being so, one is bound to ask the question: was Tom Cochrane’s work a failure? To that I say a resounding no. . . .

To put his work into a broader perspective, we must remember that the Union Medical College was just one seed sown by missionaries across the Chinese Empire. It takes its place alongside a great planting of schools, universities, orphanages, hospitals, dispensaries, bookshops, printing works, churches and chapels. . . .

China today, in the 21st century, is gripped by an inner thirst which cannot be quenched by a cocktail of egotism, materialism and digital technology. All the evidence says the nation is stirring and that a new harvest from that sowing is not far off.

Timely reminder

So, thanks are due to Andrew Adam for his fine – and relevant – reminder of Cochrane’s character, devotion and significance. Again, he puts the situation in perspective:

Today China is a superpower moving rapidly towards the centre of the world’s stage. Interest in the nation’s past is growing and we need to understand what it has come through. We also need to admit that Britain’s conduct in the 19th century did the Chinese people great harm and to hang our heads. That is the universal view in China and it is taught in the classrooms.

But equally we should not forget the good work that missionaries, doctors, educationalists, philanthropists and entrepreneurs did in China, often at great personal cost.

Thomas Cochrane and the Dragon Throne is a wonderful book. I highly recommend it for whatever church libraries are still left, and for book clubs; it will surely inspire and instruct readers, and lead to many lively discussions.

**********************

Here are a couple of tangentially-related things that I ran across and found interesting while writing this article:

- Franklin Graham has been running a Samaritan’s Purse Hospital in Central Park, New York during the coronavirus crisis, to some acclaim and at least as much disdain. (He is well remembered in these parts for his evangelistic visit three years ago, which occasioned some division within the church.) It is interesting to remember that his grandfather, on his mother’s side, served as a missionary surgeon in China for 25 years. Foreign Devil in China tells his story.

TWU professor of nursing Sonya Grypma wrote Healing Henan, subtitled ‘Canadian Nurses at the North China Mission, 1888 – 1947.’ She points out that nursing has been overlooked in the missionary record, and also describes what they brought to China:

TWU professor of nursing Sonya Grypma wrote Healing Henan, subtitled ‘Canadian Nurses at the North China Mission, 1888 – 1947.’ She points out that nursing has been overlooked in the missionary record, and also describes what they brought to China:

Missionary nurses did not bring ‘nursing’ to China. That is, if nursing is defined as a formalized system of attending to the physical needs of the ill, China had well-established nursing traditions well before missionaries came to China. . . .

What missionaries did bring to China was a particular and relatively new form of nursing practice rooted in Catholic and Protestant religious communities and adapted and popularized by Florence Nightingale after her success in caring for British soldiers in the Crimean War.

This system of professional nursing – variously called modern, Western or scientific nursing – became the standard of nursing practice in Canada and around the world.

And on another note, I had included the following portion about the lack of credit given to Cochrane in the main body of the story, but then decided to place it here as something of a footnote:

The Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH) website states that the institution – which has topped ‘China’s Hospital Rankings’ for the past decade – was founded by the Rockefeller Foundation in 1921.

While there is no mention of the missionaries’ role, the designation could still be seen as quite generous, given that China is a communist nation and name Rockefeller could not be more closely tied to the idea of foreign capitalism.

And it is true that the institution has gone through tremendous challenges since its founding – occupied by the Japanese during the war, nationalized as a symbol of American imperialism after the communists came to power, taken over for several years by the People’s Liberation Army in the 1950s and closed for several more years during the Cultural Revolution.

China’s government isn’t the only one to have overlooked Cochrane’s contribution. John Pomfret’s recent, comprehensive survey of relations between America and China over the past two centuries (The Beautiful Country and the Middle Kingdom) also asserts that the Peking Union Medical College opened in 1921, under the guidance of the Rockefeller Foundation.

Wikipedia does the college was founded in 1906, but gives credit to the various missionary societies without mentioning Cochrane.

Cochrane is by no means alone in being overlooked. As Adam pointed out in the preface to the book:

Between 1850 and 1950 approximately 1,500 doctors left Britain to serve as medical missionaries around the world. With the exception of those who were also explorers like David Livingstone or scientists like Patrick Manson, their names are largely forgotten.

Even in the Christian community, Cochrane is far from well known.

The Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions does give him a generous entry (which can be viewed on the Boston University History of Missiology site), noting:

Out of his vision and through his diplomatic skills, the Peking Union Medical College was born, with support from other mission bodies and the empress dowager, and he became to college’s first principal.

But other publications, such as the Evangelical Dictionary of World Missions, The Biographical Dictionary of Evangelicals and From Jerusalem to Irian Jaya make no mention of him or his achievements.

It is encouraging to see that Cochrane is remembered, along with fellow missionaries to China John Dudgeon and James Gilmour on the University of Glasgow’ International Story Blog.

Judging from the way he is portrayed in the book, however, Cochrane probably wouldn’t mind being overlooked for his role in founding Peking University Medical College Hospital.

An amazing story. Well done, Flyn! I’ve posted the link to this article on my FB page.

Thanks Neil; I found it quite moving myself.