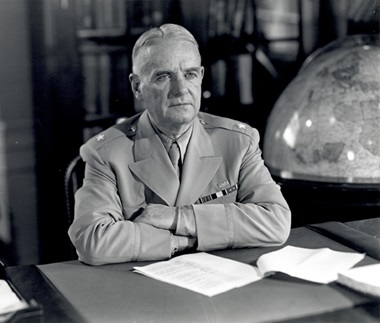

William ‘Wild Bill’ Donovan, head of the Office of Strategic Services, hired numerous missionaries to conduct espionage throughout the Second World War. (National Archives Identifier 6851006) See ‘Double Crossed’ below.

I began this series on ‘Christianity: a missionary religion’ in the lead-up to Mission Fest (February 15 – 17), both to remind people it was coming and to offer some insights into our rich missionary history and some of the issues and prospects as we move ahead.

The series

• Introduction

1. History of Missions

2. State of World Christianity

3. Specific Areas: Africa

4. Specific Areas: Asia

5. Specific Areas: Latin America

6. Not So Good News

7. New Approaches to Missions

I am looking mainly at some of the new books covering these various areas, but will also try to cover a few key themes along the way. It probably goes without saying that I will just scratch the surface of each topic – but I do hope that people will go on to read some of the books, which are of high quality.

VI. Not So Good News

Most people in our culture, including many Christians, don’t know much about missionaries. They have seen caricatures portrayed on TV and in movies, or may have read books such as James Michener’s Hawaii or Barbara Kingsolver’s Poisonwood Bible.

One widely shared quote from Hawaii reads:

In later years, it would become fashionable to say of the missionaries, “They came to the islands to do good, and they did right well.” Others made jest of the missionary slogan, “They came to a nation in darkness; they left it in light,” by pointing out: “Of course they left Hawaii lighter. They stole every goddamned thing that wasn’t nailed down.”

I read Hawaii in my teens (in a non-Christian home), and probably gained at least half my knowledge about missionaries from its pages. This quote probably still reflects common views about missionaries in the wider population. (Though one hopes most readers are now wise enough to avoid wading through turgid Michenerese.)

More recent novels – The Poisonwood Bible is the most obvious example – have confirmed a negative view of missionaries.

More recent novels – The Poisonwood Bible is the most obvious example – have confirmed a negative view of missionaries.

It tells the story of the Price family. Nathan is a Southern Baptist pastor who in 1959 becomes a missionary to the Congo. He is accompanied by his wife and four daughters, who narrate the story. Nathan is an ‘evangelical,’ in all the bad ways one might imagine – ill educated, narrow minded, fanatical, self-righteous . . .

The book is very well written; I’ve read it twice. The first time, a couple of decades ago, I noticed that while Kingsolver appended a bibliography at the end of the book, she didn’t include books by or about Dr. Helen Roseveare – who devoted her life to the Congo, returning even after being imprisoned, beaten and raped during a time of civil war in the 1960s – or any of the African American missionaries, or much about evangelicals / missionaries at all.

Timothy Larsen, writing about The Poisonwood Bible on its 25th anniversary, picked up on what I had noticed in Current:

Human nature being what it is, there is no sin known to man that has not been committed at some time by some missionary. The problem with The Poisonwood Bible is not that it makes missionaries look bad; it’s that it makes novelists look bad.

It begins with an ‘Author’s Note’ in which Kingsolver assures readers that she has done her research. This point is reinforced with a bibliography. Its 28 sources are about understanding Africa: Ritual, Magic and Initiation in the Life of an African Shaman, Venomous Snakes and Management of Snakebite in Southern Africa and so on. There is not a single source listed, however, that could help Kingsolver understand the people at the center of her story: Southern Baptists.

I wouldn’t go so far as to urge others to read The Poisonwood Bible – life is short – but I wouldn’t advise against it either. As long as they are reading some good missionary biographies and histories as well.

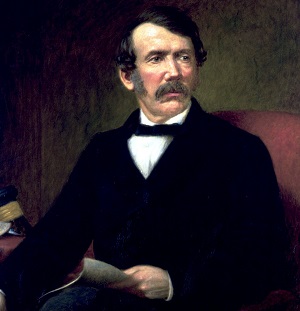

David Livingstone sought British intervention in Africa to develop cash crops and commerce as an alternative to the trade in slaves.

Not everything about missionaries in popular media is false, of course. And the more academically oriented books below discuss some of the failings related to the modern missionary movement from the West, especially from the United States.

These books are part of a legitimate discussion; some of the authors are quite sympathetic, despite their critiques. They do, at the very least, engage with all parties, including missionaries themselves.

Earlier in this series I looked at some really obvious overlaps of imperialism and missionary activity, along with examples of missionaries opposing at least the excesses of colonial power. Still, even with positive examples of missionary activity, there remain legitimate critiques, mainly related to a kind of cultural imperialism – an assumption that they were part of a ‘civilizing’ influence.

For example, Oxford professor Nigel Biggar, in Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning (William Collins, 2023) – widely criticized, and applauded, for its measured appreciation of the British Empire – writes:

Inspired by a Christian ideal of basic human equality, a popular national movement arose in late 18th century Britain to bring about the abolition, first, of the trade in slaves from Africa across the Atlantic to the Caribbean and the American colonies, and subsequently of the institution of slavery itself throughout the empire.

Thereafter, Christians and other humanitarians called for the British government to intervene in faraway parts of the world – especially West, South and East Africa – to suppress slavery.

For example, in the early 1860s, the famous Christian missionary, physician and explorer David Livingstone lobbied for the establishment of British imperial administration in the Shire Highlands of what is now Malawi, in order to provide a stable political environment for the development of cash crops and commerce as a necessary alternative to the trade in slaves.

For example, in the early 1860s, the famous Christian missionary, physician and explorer David Livingstone lobbied for the establishment of British imperial administration in the Shire Highlands of what is now Malawi, in order to provide a stable political environment for the development of cash crops and commerce as a necessary alternative to the trade in slaves.

A novel by Zimbabwean author Petina Gappah – Out of Darkness, Shining Light (Scribner, 2021) – treats Livingstone respectfully, though far from deferentially. It is told through the eyes of the African men and women who carried his body 1,500 miles across Africa when he died so his remains could be returned home to England and his work preserved there.

Here are some recent books which offer glimpses into more recent history, particularly related to the worldwide influence of American evangelicalism. Some of the write-ups will reflect my thoughts; others (in quotes) will simply be descriptions from the publisher.

- John Corrigan, Melani McAlister, Axel R. Schäfer, editors: Global Faith, Worldly Power: Evangelical Internationalism and U.S. Empire (The University of North Carolina Press, 2022)

Thirteen writers contribute to Global Faith, Worldly Power, proffering a view of Western – particularly American – missions over the past couple of hundred years which demands a sophisticated response from the modern missionary movement.

Thirteen writers contribute to Global Faith, Worldly Power, proffering a view of Western – particularly American – missions over the past couple of hundred years which demands a sophisticated response from the modern missionary movement.

The publisher says of the book:

Assessing the grand American evangelical missionary venture to convert the world, this international group of leading scholars reveals how theological imperatives have intersected with worldly imaginaries from the 19th century to the present.

Countering the stubborn notion that conservative Protestant groups have steadfastly maintained their distance from governmental and economic affairs, these experts show how believers’ ambitious investments in missionizing and humanitarianism have connected with worldly matters of empire, the Cold War, foreign policy and neoliberalism.

They show, too, how evangelicals’ international activism redefined the content and the boundaries of the movement itself. As evangelical voices from Africa, Asia and Latin America became more vocal and assertive, U.S. evangelicals took on more pluralistic, multidirectional identities not only abroad but also back home.

Applying this international perspective to the history of American evangelicalism radically changes how we understand the development and influence of evangelicalism, and of globalizing religion more broadly.

The editors state:

This fact – the reality of missions as the forward advance of an imperial project, or perhaps (and also) its retrospective justification – is crucial to understanding the role that missionaries have played in the global expansion of European and U.S. power.

The ‘civilizing mission’ was not the only task of missions, but it has been the soft edge of a great deal of hard power starting with the settler colonialism of the first European settlers in the Americas, and that fact must be central to any truly global story of American evangelicalism.

I wrote about ‘A Higher Mission,’ which covers the work of Alonzo and Althea Brown Edmiston, in Part III of this series.

They do acknowledge that “missions and missionaries could and did challenge the racial policies and imperial logic of white U.S. and European society,” offering some examples:

- African Americans were an important component of the missionary force;

- Missionaries played a key role in contesting colonial policies in the Congo;

They also note that “encounters with foreign people” meant that missionaries “were often central to an ongoing conversation about the relationship between evangelism and other social or humanitarian goals.”

The editors point out that what had been a broadly shared Protestant missionary enterprise increasingly became dominated by evangelicals:

The growing entanglement of mission work with humanitarian aid paved the way for a new divide between evangelical and mainline Protestantism that would eventually be a significant mark of difference between the two wings of the faith tradition. . . .

As David Hollinger has shown [in Protestants Abroad], in China – long the prized field for Protestant evangelization projects [and European and American imperialist adventuring] – missionaries began to have early doubts about the entire enterprise.

This changing view of missions on the part of ecumenical Protestants left the mission field far more open to evangelicals, whose missionary work exploded, particularly after World War II, when travel became easier, funds were more available and interdenominational missionary organizations flowered.

An interesting point to ponder is whether there has not developed, again, something of a divide within the evangelical movement itself, much of which now focuses on humanitarian aid.

Sarah Miller-Davenport refers to U.S. Army chaplains inviting Billy Graham and Bob Pierce (World Vision) to South Korea during the Korean War. ‘Race for Revival’ explores such issues; see write-up below.

Sarah Miller-Davenport contributes a valuable essay: ‘The Greatest Opportunity since the Birth of Christ: American Evangelical Missionaries at the Dawn of Decolonization.’ She concludes with these words:

American evangelicals approached decolonization as an opportunity for worldwide evangelism – an opportunity made all the more realizable because of how the U.S. government worked to influence decolonization’s trajectory to align with U.S. foreign policy.

Along the way they were forced to grapple with the legacies of European colonialism and the ongoing challenge of how to decouple Christianity and imperialism.

But although American evangelicals may have themselves been serving the interests of a new global empire, their own sense of righteousness was rooted in an imperial denial that washed away any doubts.

Like the United States itself, U.S. evangelicals tended to behave on the world stage as if they were representatives of a benevolent power: unwilling to confront the sins of American empire and innocent of any complicity.

Lots to discuss there. Her comments, though probably overstated, ring true.

Canadians may feel this book, and some of the ones below do not apply. Though we have our unique history and interests, and are part of a worldwide church with deep roots in history, we are nonetheless heavily influenced, for good and ill, by what goes on south of the border.

Just look at the way in which the term ‘evangelical’ has been muddied because of (some) Trump supporters and Christian nationalists. Canadians, even many in evangelical churches, do not know or care about the movement’s historic strengths or its worldwide nature.

It is hard for any Christian to know exactly how much obedience or loyalty is owed one’s government, whether imperial or not. Many missionaries do their best to ‘serve the interest’ of God’s mission, while often being naive or unthinking about how their nation’s power influences their work.

Dana Robert says Western colonialist oppression “was not what defined Christian identity worldwide.”

At any rate, one hopes that deep thinkers in missionary circles will respond openly and creatively to these critiques. I have no doubt that most contributors to this volume would be more than happy to interact with them.

One at least, Dana L. Robert, already does so regularly. As Director of the Center for Global Christianity and Mission at Boston University, she is regularly quoted in Christian publications.

I quoted her in the introduction to this series, from her contribution to a series of essays edited by Jehu Hanciles in World Christianity. In part, she said:

Western colonialist oppression, while important to face and reject, was not what defined Christian identity worldwide.

Rather than mission history being a tale of expanding empire with outposts run by colonial-era missionaries, it became clear that the margins and the center were always shifting. The local and the global constantly intersected. The seemingly powerless used their faith to create new identities.

The founding of indigenous churches, the spread of liberation theologies, the global flow of Pentecostal worship – all these were signs of vitality, not a death spiral of the Christian faith. World Christianity was not the story of Western denominations and institutions bound by rigid doctrine generated by powerful gatekeepers.

The editors of Global Faith, Worldly Power have looked back, but they are also helping us to look ahead:

In the 21st century, both the U.S. state and U.S. evangelicals are waning as global forces, in decline relative to emerging powers and a reshaped global system. . . . The question that emerges now is how the long history of evangelicals’ global faith and worldly power can help us understand the role of religion and politics on the global stage in the coming decades.

Several other recent books cover some of the same ground. The first two are by editors of Global Faith, Worldly Power; the next two are by contributors.

- Melanie McAlister: The Kingdom of God Has No Borders: A Global History of American Evangelicals (Oxford University Press, 2022)

- John Corrigan: Religious Intolerance, America and the World: A History of Forgetting and Remembering (The University of Chicago Press, 2020)

- Lauren Frances Turek: To Bring the Good News to All Nations: Evangelical Influence on Human Rights and U.S. Foreign Relations (Cornell University Press, 2020)

- Helen Jin Kim: Race for Revival: How Cold War South Korea Shaped the American Evangelical Empire (Oxford University Press, 2022)

- David R. Swartz: Facing West: American Evangelicals in an Age of World Christianity (Oxford University Press, 2020)

- Matthew Avery Sutton: Double Crossed: The Missionaries Who Spied for the United States During the Second World War (Basic Books, 2019)

Melanie McAlister’s The Kingdom of God Has No Borders won an Award of Merit from Christianity Today, but was also reviewed favourably in a diverse range of publications, including Journal of Religion, The English Historical Review and American Historical Review.

Melanie McAlister’s The Kingdom of God Has No Borders won an Award of Merit from Christianity Today, but was also reviewed favourably in a diverse range of publications, including Journal of Religion, The English Historical Review and American Historical Review.

“Because outside observers have maintained a near-relentless focus on domestic politics, the most transformative development over the last several decades – the explosive growth of Christianity in the global south – has gone unrecognized by the wider public, even as it has transformed evangelical life, both in the US and abroad.

“The Kingdom of God Has No Borders offers a daring new perspective on conservative Christianity by shifting the lens to focus on the world outside US borders. Melani McAlister offers a sweeping narrative of the last 50 years of evangelical history, weaving a fascinating tale that upends much of what we know – or think we know – about American evangelicals.

“She takes us to the Congo in the 1960s, where Christians were enmeshed in a complicated interplay of missionary zeal, Cold War politics, racial hierarchy and anti-colonial struggle.

“She shows us how evangelical efforts to convert non-Christians have placed them in direct conflict with Islam at flash points across the globe. And she examines how Christian leaders have fought to stem the tide of HIV/AIDS in Africa while at the same time supporting harsh repression of LGBTQ communities.”

John Corrigan is more critical of American-based religion, for which, he says, demonizing one’s enemies is not a new phenomenon.

John Corrigan is more critical of American-based religion, for which, he says, demonizing one’s enemies is not a new phenomenon.

“Religious Intolerance, America and the World spans from Christian colonists’ intolerance of Native Americans and the role of religion in the new republic’s foreign-policy crises to Cold War witch hunts and the persecution complexes that entangle Christians and Muslims today.

“Corrigan reveals how US churches and institutions have continuously campaigned against intolerance overseas even as they’ve abetted or performed it at home. This selective condemnation of intolerance, he shows, created a legacy of foreign policy interventions promoting religious freedom and human rights that was not reflected within America’s own borders.

“This timely, captivating book forces America to confront its claims of exceptionalism based on religious liberty – and perhaps begin to break the grotesque cycle of projection and oppression.”

In To Bring the Good News to All Nations, Lauren Turek looks at the complex and important ways in which religion shaped America’s role in the late–Cold War world.

“Using archival materials from both religious and government sources, To Bring the Good News to All Nations links the development of evangelical foreign policy lobbying to the overseas missionary agenda. Turek’s case studies – Guatemala, South Africa, and the Soviet Union – reveal the extent of Christian influence on American foreign policy from the late 1970s through the 1990s.

“Evangelical policy work also reshaped the lives of Christians overseas and contributed to a reorientation of U.S. human rights policy. Efforts to promote global evangelism and support foreign brethren led activists to push Congress to grant aid to favored, yet repressive, regimes in countries such as Guatemala while imposing economic and diplomatic sanctions on nations that persecuted Christians, such as the Soviet Union.

“Evangelical policy work also reshaped the lives of Christians overseas and contributed to a reorientation of U.S. human rights policy. Efforts to promote global evangelism and support foreign brethren led activists to push Congress to grant aid to favored, yet repressive, regimes in countries such as Guatemala while imposing economic and diplomatic sanctions on nations that persecuted Christians, such as the Soviet Union.

“This advocacy shifted the definitions and priorities of U.S. human rights policies with lasting repercussions that can be traced into the 21st century.”

Helen Jin Kim looks at Billy Graham’s largest ever ‘crusade,’ in 1973, and asks, why there?

“Race for Revival seeks not only to answer that question, but to retell the story of modern American evangelicalism through its relationship with South Korea. With the outbreak of the Korean War, the first ‘hot’ war of the Cold War era, a new generation of white fundamentalists and neo-evangelicals forged networks with South Koreans that helped turn evangelical America into an empire.

“South Korean Protestants were used to bolster the image of the US as a non-imperial beacon of democratic hope, in spite of ongoing racial inequalities. At the same time, South Koreans used these racialized transpacific networks for their own purposes, seeking to reimagine their own place in the world order. They envisioned Korea as the “new emerging Christian kingdom,” that would beat the American evangelical empire in a race for revival. Yet these nonstate networks ultimately foreshadowed the rise of the Christian Right in the US and South Korea in the 1980s and 1990s.”

Some of this is debatable. Korea had revivals well before any significant American influence. One Christianity Today article is titled: ‘Who Brought the Gospel to Korea? Koreans Did.’ Christianity grew from almost nothing in 1900 to more than 30 percent of the population today. Korea is one of the major missionary-sending nations in the world and will host the Lausanne Movement’s fourth major gathering, Seoul-Incheon 2024, this fall.

I included Facing West as part of an earlier article in this series on World Christianity. The OUP description of the book said, in part:

I included Facing West as part of an earlier article in this series on World Christianity. The OUP description of the book said, in part:

The dramatic growth of Christianity around the world in the last century has shifted the balance of power within the faith away from traditional strongholds in Europe and the United States. To be sure, evangelical populists who voted for Donald Trump have resisted certain global pressures, and Western missionaries have carried Christian Americanism abroad.

But the line of influence has also run the other way. David R. Swartz demonstrates that evangelicals in the Global South spoke back to American evangelicals on matters of race, imperialism, theology, sexuality and social justice. From the left, they pushed for racial egalitarianism, ecumenism and more substantial development efforts. From the right, they advocated for a conservative sexual ethic grounded in postcolonial logic.

Go here for the rest.

As leader of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS, precursor to the CIA) during World War Two, William ‘Wild Bill’ Donovan ran across missionaries, and decided that what makes a good missionary would make a good spy.” He recruited various religious figures to work and spy for the OSS.

“In Double Crossed, historian Matthew Avery Sutton tells the extraordinary story of the entwined roles of spy-craft and faith in a world at war.

“In Double Crossed, historian Matthew Avery Sutton tells the extraordinary story of the entwined roles of spy-craft and faith in a world at war.

Missionaries, priests and rabbis, acutely aware of how their actions seemingly conflicted with their spiritual calling, carried out covert operations, bombings and assassinations within the centers of global religious power, including Mecca, the Vatican and Palestine.

“Working for eternal rewards rather than temporal spoils, these loyal secret soldiers proved willing to sacrifice and even to die for Franklin Roosevelt’s crusade for global freedom of religion.

“Chosen for their intelligence, powers of persuasion and ability to seamlessly blend into different environments, Donovan’s recruits included people like John Birch, who led guerilla attacks against the Japanese, William Eddy, who laid the groundwork for the Allied invasion of North Africa, and Stewart Herman, who dropped lone-wolf agents into Nazi Germany.

“After securing victory, those who survived helped establish the CIA, ensuring that religion continued to influence American foreign policy.”

But Sutton also writes that things have changed. In the final chapter of Double Crossed, he describes the determined efforts of evangelical Senator Mark Hatfield:

He argued that CIA involvement with clergy, members of religious orders and missionaries “tarnishes the image of the United States in foreign countries and prostitutes the church.”

Sutton concludes that “much has changed” since World War Two:

Government agencies are now more willing to honor the separation of church and state, and they do not want to endanger missionaries around the globe. This suits religious activists. They understand that close affiliation with their government can sometimes undermine rather than bolster their missionary efforts.

Writing positively about Double Crossed for Christianity Today, Cambridge professor Andrew Preston said:

US foreign policy will be less successful if people believe it to be simply conflated with Christian mission. Yet difficult doesn’t mean impossible, and it certainly shouldn’t mean that religious Americans cease trying to align American foreign policy commitments with their moral convictions.

Preston wrote Sword of the Spirit, Shield of Faith: Religion in American War and Democracy (Vintage Canada, 2012)

Preston wrote Sword of the Spirit, Shield of Faith: Religion in American War and Democracy (Vintage Canada, 2012)

Oxford University Press published John Birch: A Life by Terry Lautz in 2016. Global Asia said of the book:

Lautz painstakingly reconstructs the brief life of this missionary, soldier and spy, who arrived in China to save souls in 1940 and was shot dead by Communist soldiers five years later. Birch becomes a case study in the “well-meaning idealism and misguided adventurism” that had animated the interest of Americans in China since the 19th century. . . . Lautz has written an enlightening reflection on a complex history.

Back to Hawaii

James Michener wasn’t keen on missionaries. The statement quoted above referred to Abner Hale, a key missionary figure in Hawaii. To be fair to Michener, though, he did add this, about Abner’s wife:

James Michener wasn’t keen on missionaries. The statement quoted above referred to Abner Hale, a key missionary figure in Hawaii. To be fair to Michener, though, he did add this, about Abner’s wife:

But these comments did not apply to Jerusha Hale. From her body came a line of men and women who would civilize the islands and organize them into meaningful patterns. Her name would be on libraries, on museums, on chairs of medicine, on church scholarships.

From a mean grass house, in which she worked herself to death, she brought humanity and love to an often brutal seaport, and with her needle and reading primer she taught the women of Maui more about decency and civilization than all the words of her husband accomplished.

She asked for nothing, gave her love without stint and grew to cherish the land she served: “Of her bones was Hawaii built.” Whenever I think of a missionary, I think of Jerusha Hale.

There have been, and are, tens of thousands of Abner and Jerusha Hales who have devoted their lives to spreading the gospel as missionaries. Most are not as bad as Abner or as good as Jerusha – at least as Michener painted them – but most did their best to follow the Great Commission, to the best of their understanding.

We are fortunate, in retrospect, to have so many new written assessments and critiques of their work, which can help Christians to do better in the future.

Thanks for your thoughtful reflection on missions, the good, the bad and the ugly, Flyn. It was great to see you at Mission Fest 2024, which to me is beauty for ashes. (Isaiah 61)

I am glad that you mentioned Helen Roseveare, a remarkable missionary with deep integrity. You might remember my article on her in the Light Magazine:

https://lightmagazine.ca/dr-helen-roseveare-the-fellowship-of-his-sufferings/ https://www.academia.edu/86419322/Examining_the_Lasting_Medical_Impact_of_Dr_Helen_Roseveare_in_the_Congo

Thanks Ed. Yes, it was great to see Mission Fest up and running again this year, and to see old friends and new there.

Good article about Helen Roseveare, and thanks also for your God’s Firestarters book which profiles a number of missionaries.

I was fortunate to meet and interview Dr. Roseveare many years ago, when she came for Missions Fest.